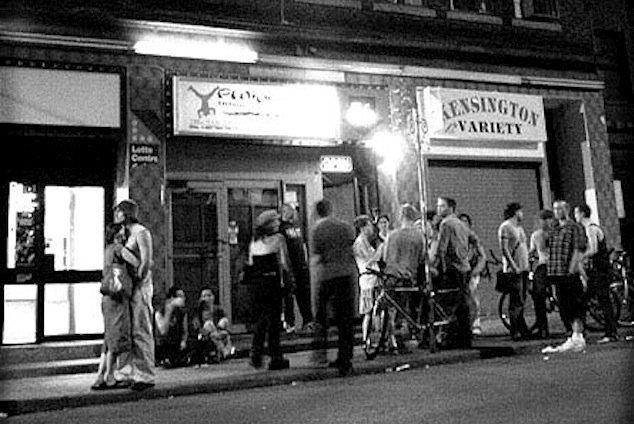

Outside Club 56. Photo by RANDREAC.

Article originally published November 12, 2013 by The Grid online (thegridto.com).

It was a dark, dingy death-trap. But in the early 2000s, there was no better place to party than in this Kensington basement.

BY: DENISE BENSON

Club: Club 56, 56C Kensington Ave.

Years in operation: 2001-2004

History: In the early 2000s, Kensington Market was not much of a destination for dancing. Market nightlife mainly consisted of punk and reggae shows, the occasional low-key lounge or restaurant, impromptu gatherings in the park, and boozecans. Streets tended to be quiet by night and busy by day, when people flooded in to buy vegetables and second-hand clothes.

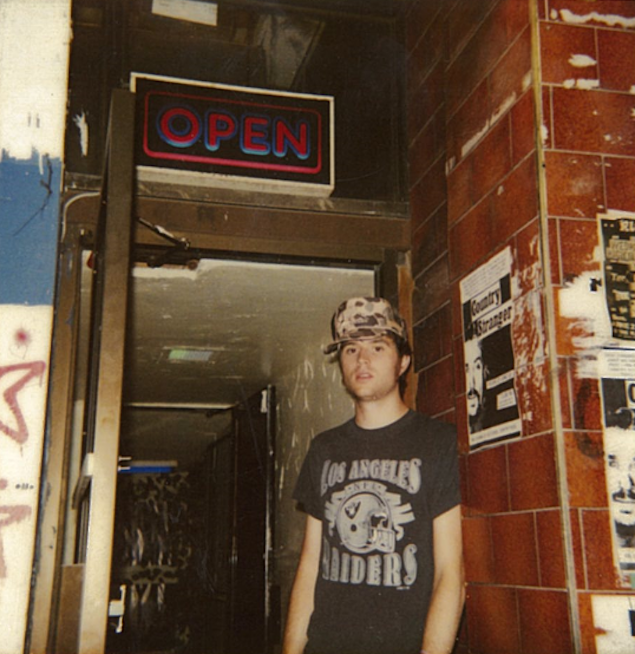

Squeezed between random storefronts and a TD bank machine, 56C Kensington was easy to miss. Its glass-door entrance was set in from the sidewalk, and was frequently covered in posters. Layers of paint hinted at the location’s past lives, including as an after-hours and, before that, a Vietnamese karaoke bar.

By 2001, a man named Laszlo or Leslye (the English translation) owned the basement bar that came to be known as Club 56. At first, his clientele consisted largely of friends, many of them fellow Hungarians and other Eastern Europeans. It was a social club of sorts.

That same year, a DJ and promoter named Mike Wallace was searching for a new spot to throw his parties. He and Rob Judges—two Scarborough-raised music lovers who’d been friends since grade four—had made names for themselves through a party called Skeme. From 1995 to ’97, the duo scoped underused spaces, bouncing from legion halls to Ethiopian restaurants, Kensington’s Lion Bar and Top o’ the Market and, most successfully, to Spadina’s Club Shanghai.

“We got big by basically being the only party at the time to play Britpop alongside hip-hop, with lots of ’60s nuggets thrown in,” says Judges. “We’d go Wu-Tang into Supergrass into Chambers Brothers, and it worked.”

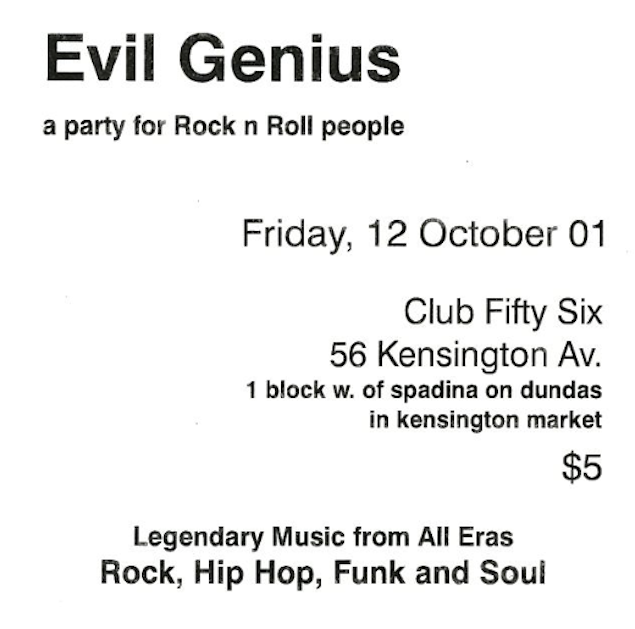

Wallace moved to London, England in 1997. By the time he returned, in summer of 2000, Judges lived in Tokyo. That December, Wallace started his own soul and indie-rock party, dubbed Evil Genius, at Manhattan Club on Balmuto.

“By the summer 2001, I’d been throwing Evil Genius for six months, and was on the lookout for a new venue,” writes Wallace by email. “Walking around the Market, I saw the outside door for Club 56 and was intrigued, but every time I went by, the door was locked. Then, one day in September, I found it open, went downstairs into the club and thought, ‘Yes, totally—this is the place.’

“It was well laid-out, with good integration and separation of bar, lounge, and dancefloor areas. With a low ceiling and lots of mirrors, it would be easy to make any crowd look big. 56 had a sort of jungle-grotto theme, vaguely tropical, gone to seed; plastic foliage dripping from the decaying ceiling, along with various cables and wires and other infrastructure. It looked like it was just about to fall apart, and gave off a sense of impending peril. It looked like an exciting place to party.”

Wallace spoke with a bartender named Charlie, the owner’s friend, who told him the bar was available for parties.

“I called Leslye that night and left a message. A couple of days later, he called around 10 p.m., said he’d like to meet, and asked where I lived. I told him Yonge and Carlton, and he said to meet him downstairs, outside, in 15 minutes. I stood in front of my building, and a silver Mercedes glided to a stop. The window slid down, and there was Leslye in the driver’s seat. ‘You want to do a party?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘When?’ ‘Three weeks from Friday.’ ‘Okay, see you then.’ We shook hands, and he drove off into the night.”

The first Evil Genius at Club 56 went off in October of 2001.

“The party was packed, and everyone loved the place right away,” recalls Wallace. “Leslye and Charlie were wonderful hosts—generous, welcoming, laid back, super cool.”

Though he would never be privy to either man’s surname (“they were friendly guys, but cagey; we didn’t get into a lot of getting-to-know-each-other”), Wallace had found his new party spot. Other adventurous promoters would soon follow his lead.

Why it was important: By the early 2000s, Toronto club-goers were restless. Our once-mighty rave scene was imploding, but its influence and energy still widely felt. Venues in the Entertainment District were heavily skewed to commercial music and faux-luxury—turn-offs for many. A lot of people who’d grown up listening to a range of sounds had become bored by sonically specialized nights. There would soon be a gritty, sweaty, and artfully rebellious response as huge events and swank superclubs were eschewed in favour of warehouse parties and raw, intimate spaces. Club 56 quickly became a hotspot.

“56 was by no means a beautiful place; it was, however, not without its charm,” says DJ Dougie Boom, who would get his start at the venue in 2002. “Its low ceiling and bunkered-down quality had the seediness of an after-hours, which appealed to the kids, but had the familiarity of a suburban basement, which made it more accessible, in some respects. Geographically, it was also appealing, being slightly off the beaten path, but situated between College and Queen.

“You would walk through the glass door and slink down the stairs. The walls in the staircase were covered with mirrors and coloured light bulbs, like a funhouse or an old arcade, but, more probably, were just remnants of its 1970s incarnation as a bar. Once you hit ground level, you usually had to wait to pay and get past security through these narrow doors. The room was small, maybe 80-person capacity legally, and was rather dark.”

The club itself was basically a square, with a corner dancefloor on the right, and a small bar and lounge, complete with grotty black leather couches, on the left. The colour scheme was black, blue, and purple—made more intense by multiple black lights, many of which shone on fish tanks scattered around the space. Walls were wood panel painted black on bottom, with mirrors on top. Most of the floor was ceramic tile, with a linoleum dancefloor. The washrooms frequently flooded.

“56 was a great club for dancing,” says Wallace. “The checkboard linoleum was perfect for sliding. I liked the seediness of it. The down-the-stairs entrance was like going down the rabbit hole. It felt tight, cramped; you knew you’d get touched. Club 56 was ridiculous in the best way, with the fish tanks and plastic grape bunches. People were always at ease there.”

“It was a mouth-wateringly perfect place to throw a party,” adds Judges.

Many promoters and DJs felt the same way. Club 56 would become ground zero for a creative, somewhat anarchic approach to party-throwing, where visuals meant as much as the open-format music mix.

This edition of Then & Now is, in fact, as much about individual events held at 56 as it is about the club itself.

Evil Genius was ahead of the curve, practically sending a flare out in the night sky; its parties were packed with enthusiastic indie kids who got down to Wallace’s blend of hip-hop, funk, soul and classic rock.

“The Evil Genius flyers used to say ‘Legendary Music from All Eras,’” Wallace recalls. “There were no constraints; anything went.”

He cites signature tracks like Nelly’s “Country Grammar,” April Wine’s version of “Could Have Been a Lady,” Beatnuts’ “Hellraiser,” “Don’t Bring Me Down” by E.L.O., “Exploration” by Karminsky Experience, and Sweet’s “Fox on the Run.”

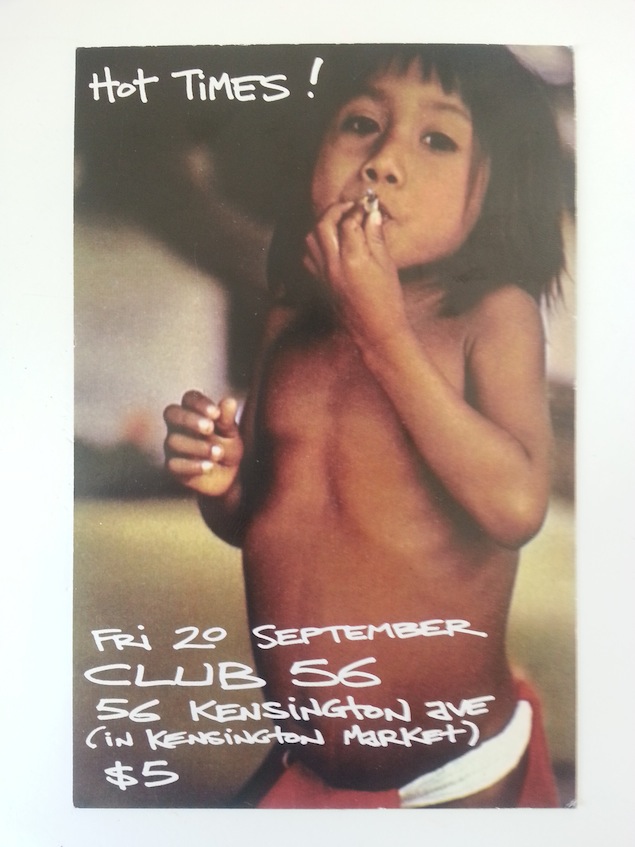

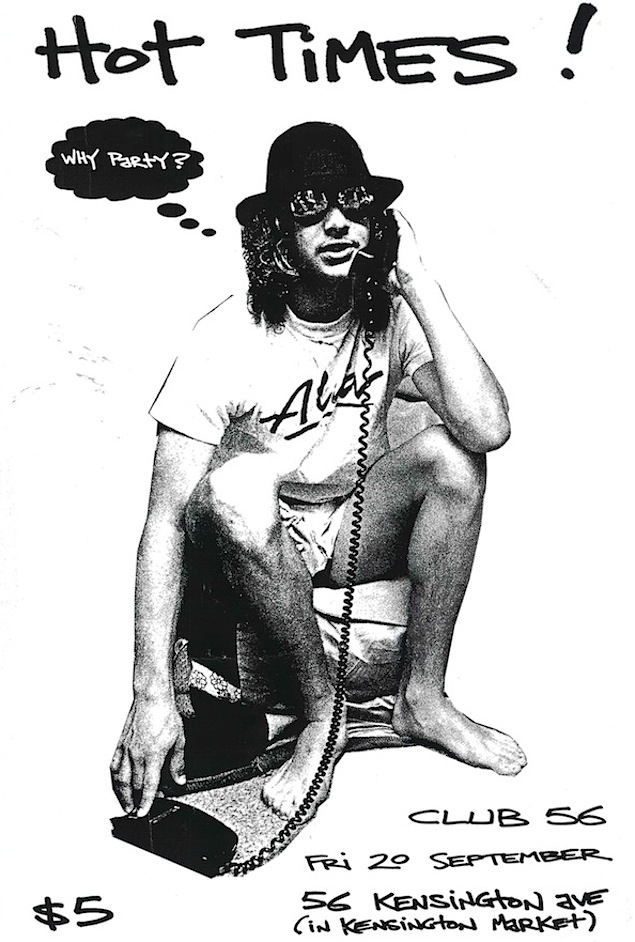

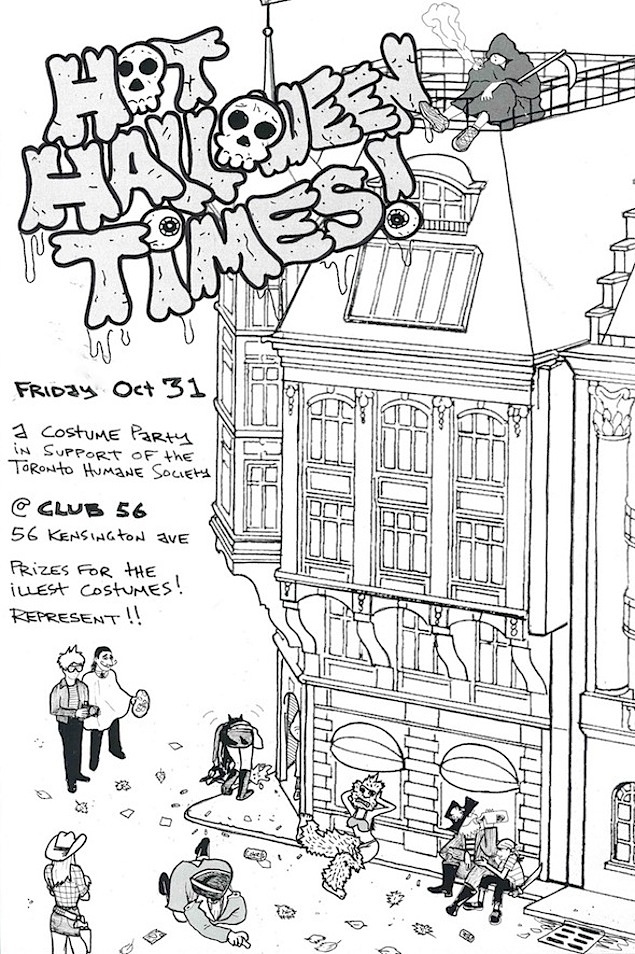

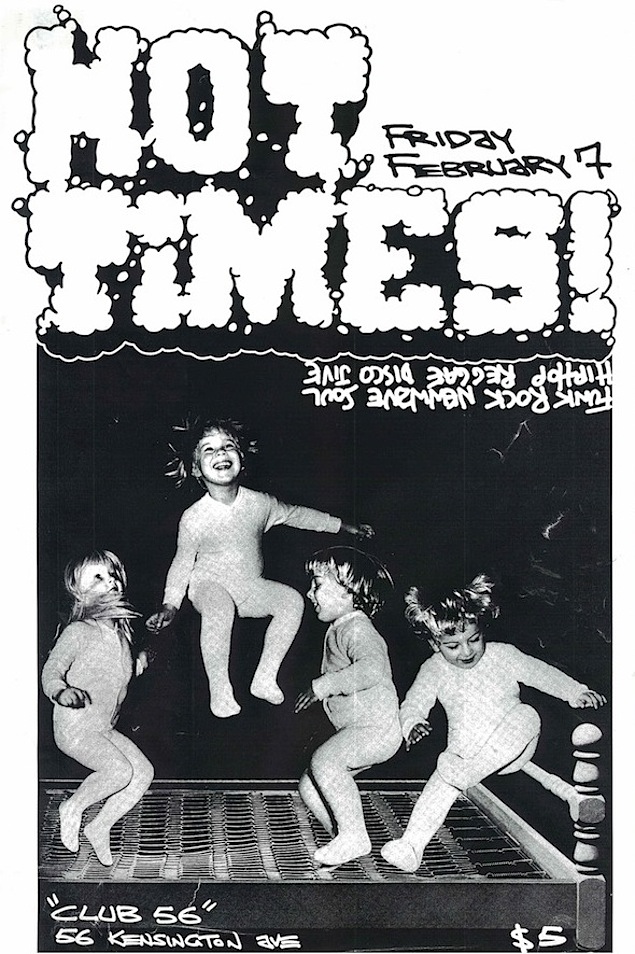

Evil Genius was an anchor monthly at Club 56 until July 2002. By then, Judges had returned from Japan, and the two dreamed up a new collaborative party, called Hot Times! It launched that September, and was packed from day one. The signature flyers created by Judges were definitely part of the Hot Times! appeal.

“Our flyers asked, ‘Why party?’ and we deliberately spelled things wrong,” explains Judges. “It was never rude, but always sort of deliberately provocative or off—a flash of nipple, a smoking child, scientific-research animals.”

Hot Times! flyers courtesy of Mike Wallace and Rob Judges.

As with the pair’s earlier Skeme parties, Hot Times! zoomed in on hip-hop and rock, but Judges’ music collection had expanded greatly.

“I had brought back tons of music from Japan—mostly Japanese reissues of obscure funk, soul, and rock. But we loved our new stuff, too. Hot Times! was about good music, period.”

His eclectic list of top picks includes “Better Change Your Mind” by Nigeria’s William Onyeabor, Kool G Rap and RZA’s “Cakes,” “Barely Legal” by The Strokes, “Electronic Renaissance” by Belle & Sebastian, The Dave Pike Set’s “Mathar,” and “Hard Times” by Human League.

“That was major. The crowd would sing along to it as ‘Hot Times!,’ which was always my favourite part of the night.

“The DJ booth was built over a fish tank, but you would barely notice it because there were wires and cables everywhere,” Judges continues. “I had no idea what was connected to what, and it always felt like a miracle that the sound ever worked. Our rule of thumb was just ‘Don’t touch anything.’ Seriously, those cables were like the Da Vinci code.”

“The soundsystem was makeshift—lots of scotch tape, lots of improvisation,” Wallace confirms. “The dynamics might not have been optimal, but it always worked and it was always loud.”

Wallace also lovingly details the club’s main visual elements. “The several aquariums scattered about the room each had a few hardy fish. They looked amazing. There was also a single moving colour light, and a small disco ball, with one dim spotlight. Because the ceiling was low, people always hit the disco ball, so the lights were off-kilter, drunken.

“I have no idea how Leslye came to own Club 56, but I do know he loved owning it,” adds Wallace, who also did a run of old-school country nights, called Country Stranger, at 56.

“What I remember most is how he’d always talk about his plans for the future, how he wanted to buy the place next door, tear down the wall, make Club 56 twice as big, and put a huge shark tank behind the bar.”

Wallace and Judges would continue Hot Times! together until January of 2003. When Wallace left to restart Evil Genius and to focus on his band, Snowy Owl, another Scarborough friend, Adam Bronstorph, stepped in to DJ alongside Judges.

Both Evil Genius and Hot Times! were consistently rammed. Owner Leslye was both flexible with capacity, and very open to booking other idiosyncratic DJ events.

“Leslye was a businessman all the way,” says Judges. “It always came down to cash for him, but he knew that meant delivering customer satisfaction. He and Charlie were always cool with our crowds, and were never stressed, even when we’d have 50 people on the street trying to get in, and cops showing up. Leslye was just unflappable.”

“Leslye was always in control,” Wallace agrees. “But I think he was bemused by the parties, by the people who went to them, and the people who threw them.”

Lara McMahon, who bartended at Club 56 for roughly a year, offers this take on her former boss: “I think Les had the original intention of opening a fancier style lounge that would cater to an Eastern Bloc crowd, but found that money was in the DJ parties. The crowd there was hip before there were hipsters. They were young, and had money to burn until the morning. On more than a few occasions, Les would lock the door and serve until the sun came up.”

By fate rather than design, Club 56 became a breeding ground for a new wave of hybrid sounds and crowds. Events that happened there connected crowds and communities that were once divided.

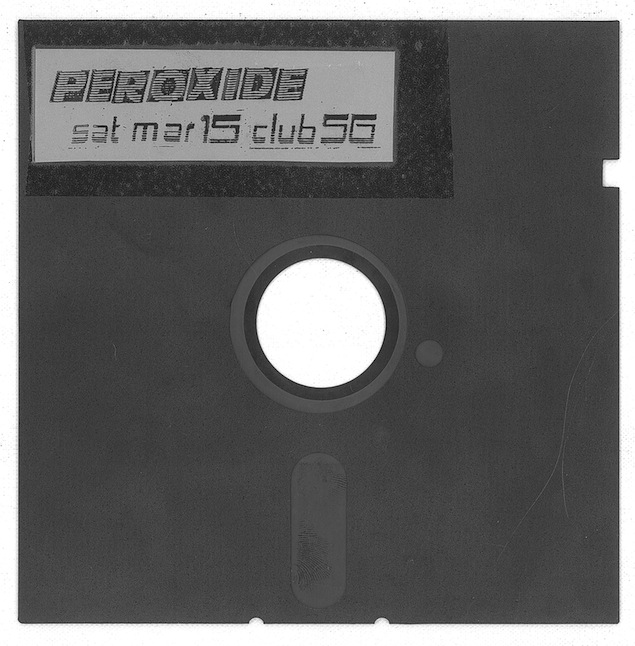

The late Will Munro’s Peroxide parties are another great example. By January 2002, when the artist and DJ kicked off his electro-centric monthly, he already had a huge hit in the form of alt-queer event Vazaleen, by then held at Lee’s Palace. Peroxide was a chance for him to showcase the electronic sounds he loved in a much more intimate venue.

The party attracted a wide range of queers, artists, electro-heads, and others with open ears and minds. One regular was future DJ Jaime Sin. Though she did not yet know Munro—they would DJ and plan events together years later—Sin made a point of attending his nights.

“I remember Will passing me a baggie one night, and whispering, ‘drugs!,’” relates Sin. (Munro was straight-edge and avoided drugs.) “It was actually a Peroxide flyer—some kind of electronic part contained in a baggie with the name and date of the party stickered on. Amazing.”

“Will had a knack for making the invitations to his events like works of art that made you not want to miss a night,” echoes artist and curator Luis Jacob, a friend and frequent collaborator of Munro’s.

“For Peroxide, Will rummaged through the bins of Active Surplus on Queen so that the invites had a kind of ‘obsolete technology’ feel to them. At various times, he’d use floppy disks, resistors, and other bits and pieces of gadgetry. The fonts he’d use also had a cold ’80s new wave feel to them, which would match perfectly the cold, arpeggiated electro coming out in the early 2000s. The club itself had a late ’80s feel, so the flyers, music, and physical venue all came together to create this dark, hard, and cool vibe.”

Jacob was a regular at Peroxide and would later do parties at Club 56 dubbed Rhythm Box (named in relation to a standout scene from 1982 cult film Liquid Sky). Jacob DJed as Didi7 and—along with Prince Jiffar and The Robotic Kid—played a mix of house, acid, and techno a la Green Velvet’s “Land of the Lost” and A Number Of Names’ “Sharevari.”

“At 56, you really felt that you had arrived at an end-of-the-world party, decorated by mirrored walls, and populated by exotic fish glowing in the dark,” Jacob recounts. “People used to nervously joke that if there ever was a fire, we would all meet a certain death since there was no way everyone would make it through the stairs to safety.

“What I remember most is the heat. I distinctly recall one summer night—though the place was equally hot in the winter—coming outside to get some air. I had been dancing, wearing a green fishnet sleeveless top. I took off my shirt, wrung it, and sweat just gushed out. I couldn’t believe that something made of such little cloth could contain so much liquid. That’s Peroxide at 56 for you!”

Sin shares a related memory.

“When 56 got full, the mirrors would get covered in condensation, and if it got really busy the ceiling would start to drip. At one Peroxide party, there was this amazing-looking girl wearing like, neon socks and clear, platform stripper heels, and I remember thinking, ‘Oh my god, that’s brave!’ because those floors were damn slippery.”

Club 56 was an unabashedly raw space, but the creativity served up made it exciting.

“I liked the dinginess and the slightly down-and-out quality 56 had,” says Luca Lucarini, also known as DJ Captain Easychord. “Basically it was a shithole, in the best way possible.”

Lucarini was a Kensington Market resident who’d already been to the club plenty by the time he and friend Tom Khan started the Expensive Shit party there in 2002. Khan was a big soul and Afro-funk fan (the party got its name from Fela Kuti’s legendary 1975 album) while Lucarini also loved indie and experimental sounds.

After a bunch of parties, Rob Gordon would step up as Lucarini’s DJ partner. Gordon was a high-school friend, a drummer (he would play in bands including Les Mouches, From Fiction, and Pony da Look), and, in 2000, he’d started to mix his dad’s soul seven-inches with indie rock at bars on College and beyond. After a chance encounter in 2002, when Lucarini flyered Gordon and invited him to an Expensive Shit party that night, the two re-connected.

“We had a long talk and agreed it was time to break from some prevailing form,” Gordon recalls. “The dancefloor fillers from the mod and indie scene had become impotent. We craved something futuristic, yet without the overtly futuristic aesthetic of techno, which was amazing, but certainly nothing new at that time. Toronto nightlife had already begun its organic transformation in this very direction, and we were just another couple of people feeling its traction. Many others felt the same pull, and were already doing something about it. Strangely, they were all doing it at Club 56. I started to attend all the parties at that club, and it really seemed everybody wanted to create the same kind of experience; they just had a more personal flavour to their selections or their approach to mixing.”

Expensive Shit became known for well-programmed sounds that ranged from riot grrrl to Krautrock, Dat Politics to dancehall, DFA to Dizzee Rascal, and other grime, soul, mash-ups and indie rock, often recorded by their many friends connected to Blocks Recording Club. Another friend, Dan Brown, created the psychedelic projections while Peter Venuto’s LED “Trash Lights” synched to the beat as they lit up four different garbage-can lids. Additional sound gear, especially subs for added bass, was rented for the parties.

“The 56 sound system was always budget, and very often actually busted,” Gordon recalls. “This supplied a kind of natural punk vibe to everything that went down there. Italo disco and New York no wave came out of the speakers sounding the same.”

“I remember when we could come in and do soundchecks, Laszlo would always insist on blasting trance, and quite often he would try and take over on the decks mid-party,” adds Lucarini, who also acknowledges that the owner’s “laissez-faire attitude toward capacity was a major part in our party’s success.”

So was live music.

“Everybody at that time was either in a band, or going to check out literally anything [promoter] Mikey Apples would bring to town, so it became regular practice to have a band play before the party would start,” states Gordon. “Drums were banned, probably by me, and there were tonnes of great shows right in front of the DJ booth. Steve Kado famously recorded a version of [OutKast's] ‘Hey Ya,’ and performed it before it was even released. I also have fond memories of d’omain d’or performing their anemic Jesus song, and Oh No the Modulator smashing a pile of vintage computers.”

Mikey Apples both attended and promoted parties at Club 56. He also produced many pioneering events, booking bands with “a punk approach to night music” into a variety of venues in the early 2000s.

“There was a great energy around that scene at the time, not just related to 56,” recounts Apples. “There was the Manhattan Club, up behind the old Uptown cinema, a random Chinese restaurant, a gallery—we were always on the hunt for a new one-off spot. It made it an adventure.

“I wanted to contribute to that momentum, and started doing semi-regular parties at 56. At the same time, I was doing more hybrid concert-party things at Xpace on Augusta, and other raw spaces like Cinecycle.” (He booked bands like The Gossip, Les Georges Leningrad, Numbers, and Ninja High School, and also presented some of the earliest ticketed shows at The Boat, including Glass Candy, Aidswolf, Ariel Pink’s debut Toronto show, and Crystal Castles’ second-ever performance.)

“Dance music was finding its way into something new, and these parties were a mix of what little cool new stuff we could find mixed with old, overlooked gems that fit,” says Apples, pointing to big tunes of the time like The Rapture’s “House of Jealous Lovers,” and LCD Soundsystem’s “Losing My Edge” as examples.

“Most of us that played at Club 56, or during that time, were very good at blending the eras and creating a vibe. It was very exploratory. All of us also put a lot of heart and soul into the experience, like with lots of small details in the promo. Will [Munro]‘s stuff was extraordinary.

“The visual element, the incredible, tangible, often hand-made promo—this stuff was priority numero uno, not numbers or money,” Apples emphasizes. “It felt very pure, very honest and heartfelt.”

Will Munro-designed Peroxide posters. Courtesy of Jaime Sin.

“When Will Munro took Peroxide to 56, that was like getting the ultimate seal of approval,” says Wallace. “Will was the coolest cat in the city by far. I also remember when Expensive Shit started there; it felt like a generational handshake. They were the new kids to us old kids. I loved their night—a fantastic party. Everything that happened at Club 56 was awesome. It was just that kind of space.”

“Ultimately, Club 56 was a temple of tolerance that allowed young creative energy to explode with reckless abandon,” enthuses Expensive Shit’s Gordon. “I remember it being so unbearably sweaty that everybody started stripping. I remember everybody making out, people hooking up right on the couches, fuelled by a creatively hyper, totally ambiguous sense of sexuality. The energy of every party was so high that it was too much for the little club.”

“The energy on some of the nights in that little basement was pretty spellbinding,” concurs Apples. “Everyone just went for it, with all this great off-the-beaten-path music that had never been put together and presented as something to dance to, at least to the particular generation in attendance. They couldn’t properly fit the amount of people that used to ram in there. It was a very small space, but that’s what lent the place the energy it had. Like atoms smashing together.”

Who else played/worked there: There was a vitality to Club 56 that far outweighed its size; the community that frequented it was ever-expanding, largely through word-of-mouth.

“It was right before everyone used the internet to find out about or communicate everything,” reminds Sin. “Spots did not get blown up so quickly, like they do now.”

Club 56 attracted the curious, the creative, and those who just wanted to do their own thing.

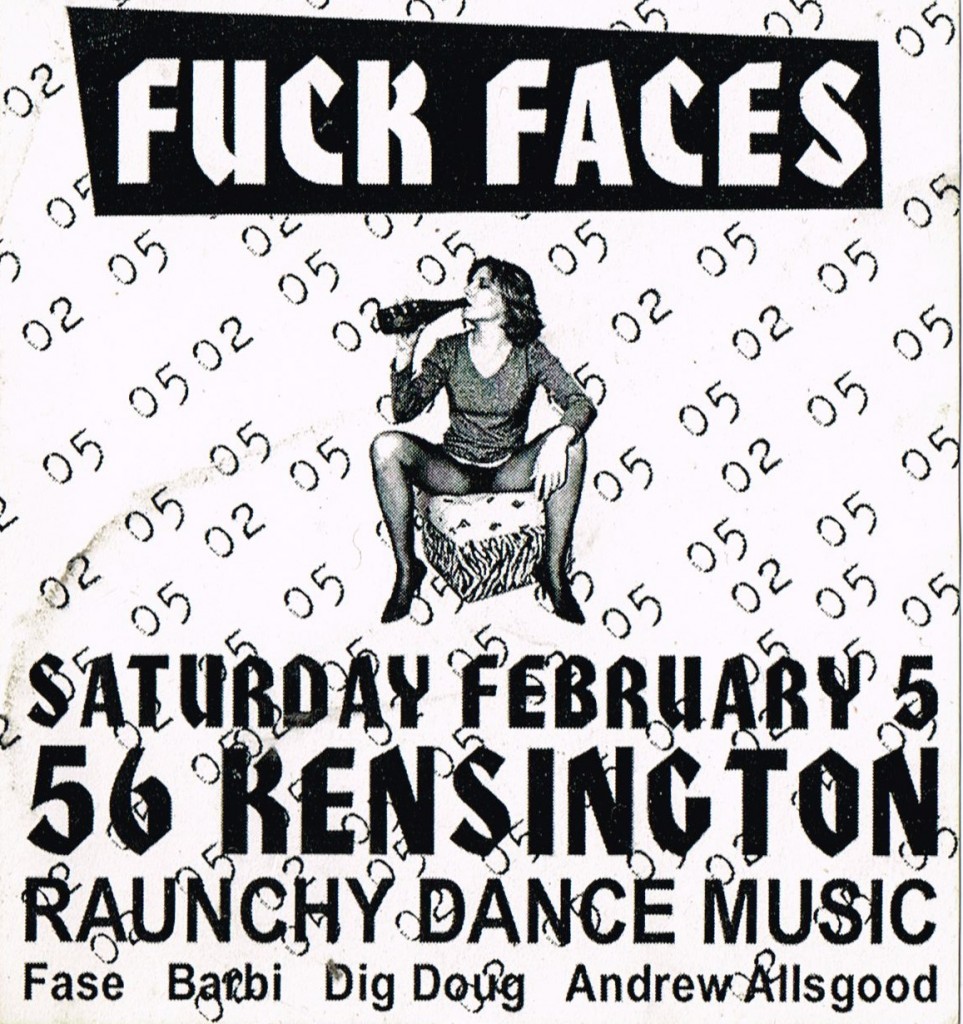

It’s where Darcy “Diggy” Scott got his start as a promoter, before he would work under the name of D-Money. He had attended Peroxide and other nights at 56 before he and friend Steven Artimew started to do events there in the summer of 2002. By early 2003, they went monthly, and named their party Fuck Faces.

“It was aggro dance-party fare,” Scott explains. “There was lots of hair-metal mixed with house, ghettotech stuff, and hip-hop. We were definitely less about a groove, and more about a party. At the time, open format nights were a new idea, for us, and what we brought to the table were DJs with technical skills. There were a couple of open-format monthlies at the time, but the DJs were more musical curators.”

Fuck Faces featured gifted DJs including Andrew Allsgood, Fase, Barbi, Cryo, and Andrew Ross, as well as a newbie named Dig Doug. The man now known as Dougie Boom says the mix of raunchy dance music played at Fuck Faces mirrored the time and place.

“If you were our age or demographic, you probably grew up on rock and new wave in the ’80s, listened to Wu-Tang Clan in the ’90s, and then got into club music in the later ’90s,” explains Boom. “So there was that musical past, but then we mixed in electro, booty, Miami Bass, and ghetto-house as well. It required a certain amount of conviction.”

56 was a perfect fit for the crew.

“It was a spot that we could do whatever we wanted in,” says Scott bluntly.

Asked about his key memories of the space, Scott mentions “The ‘Very Cheap Special.’ It was this glass dome that sat on the bar top, and it had like three-month-old sandwiches in it. It was disgusting.

“56 also routinely ran out of booze, forcing us to call everyone’s favourite after-hours booze delivery company in order to keep the party going.”

“The parties were just banging,” says Boom. “At the end of the night, the floor would be a mess: condensation; cigarette butts, and glass. If we had had computers for DJing at the time, they probably wouldn’t have survived.”

Fuck Faces would continue at 56 into 2004, but outgrew it, and moved on to The Boat, Sneaky Dee’s and, finally, Wrongbar (where it ended in 2010).

“Club 56 was a small step in the long run for Fuck Faces, but it probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise,” says Boom, who now DJs all over the city and is producing music.

He and Scott are also two of the driving forces behind Neighbourhood Watch, a party series that will also fund releases by Toronto-based artists.

Scott’s D-Money promotions grew to become Underdog, which now presents a variety of concerts and parties, including the intrepid Galapagos series. Scott also produces, and records with XI as Ambalance.

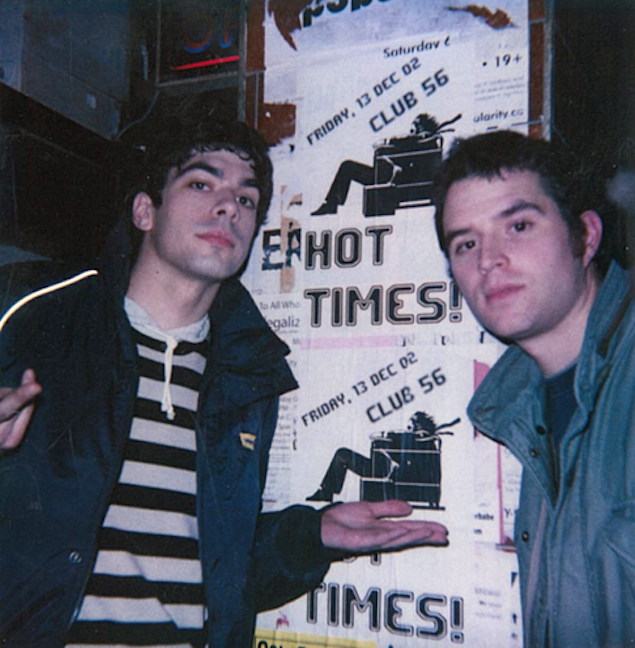

A lot of Toronto musicians hung at Club 56—Wallace mentions that “Crystal Castles’ Claudio, Death From Above 1979’s Jesse and Sebastian, Sam Roberts Band members, and many others” partied at Evil Genius and Hot Times!

Jesse Keeler of Death From Above 1979/MSTRKRFT (right), with friend Dennis Chow.

Photo: Mike Wallace.

56 was well-loved for a variety of distinctive parties, which also included deep-funk, rhythm and blues, and garage-rock night Doing It to Death, with DJs Wes Allen and Dan Vila; hip-hop party Let The Hustlers Play with DJs Islamabad and Big Jacks; and superheavyREGGAE, with selectors Jeremiah and Friendlyness, hornsman I-Sax, and a variety of guests.

“The nights that stood out most to me were the superheavyREGGAE parties,” says Franzisca Barczyk, who bartended briefly at Club 56, while a U of T student. “They were always really packed, loud, and there was always a real variety of people.

“Club 56 felt like it was a hidden party spot with a variety of random people,” she adds. “The crowds were completely mixed. Some nights were more student-y. The vibe was always about music and dancing.”

Barczyk got the bartending job offer from Leslye, as did friend Francesca Bungaro-Yemec, when they attended an OCAD party at Club 56 one night in 2002. Francesca had previously tended bar at Babylon on Church Street.

“The first night I was at 56, some crazy drunk girl flushed her cellphone down the toilet, and the mess it made convinced me to never use the washroom,” Bungaro-Yemec recalls. “I would occasionally provide an extra roll of toilet paper over the bar, but that was as close as I got. The back room was also a place I never dared to venture; rumours of ghosts or something sordid kept me out.”

Other familiar faces from Club 56 include Dave Wallace, Mike’s brother, who did door at both Evil Genius and Hot Times!

“He would always do an inspection of the club before a party,” says Wallace. “He’d check the fire extinguisher, try the emergency exit, and pull out the exposed nails that littered the club. ‘This place is a death trap, Mikey,’ he’d say. But we never had any hassle at the door.”

56, ramshackle as it was, would serve as inspiration for many Toronto clubs to come.

“Club 56 showed people that when it came to nightlife, anyone could do it and anything was possible,” states Wallace. “It was a punk-rock space, no matter what music was playing.”

Judges credits Wallace not only for “discovering” 56, but also being one of the first to scout Market spots like The Boat and Top o’ the Market for parties.

“And so, people were not only hearing these open-format type nights, they were getting to see the inside of places they didn’t even realize were there,” Judges says. “Perhaps these nights, and 56, helped open people’s minds up to the idea that a party could happen anywhere, and that with a little creativity and love for what you do, a scuzzy, local dive could be the coolest place in Toronto to be at on a certain night. It was pure DIY, all the way.”

What happened to it: Just like the fish seemed to disappear one-by-one from the Club 56 aquariums, most of its popular dance parties gradually moved to larger venues.

“Our own friends couldn’t even get in to Hot Times!,” says Judges, who left 56 in 2003. “There just physically wasn’t any more room for people, and the crowds on the street outside became a total heatscore.”

Hot Times! moved to Ras Dashen, The Gladstone, Silver Dollar, and the El Mocambo before wrapping in March 2005 at the then newly-opened Supermarket in Kensington. (A visual artist, Judges moved back to Tokyo in 2005 and launched a version of Hot Times! It has since morphed into collaborative party Hindu Love.)

Mikey Apples had stopped doing events at 56 by the time he and Jaime Sin launched Shack Up! Thursdays at Queen and Bathurst dive The Queenshead in 2004. Shack Up! helped that pub become a beacon of cool as they hosted the likes of James Murphy, Juan Maclean, Arthur Baker, and MSTRKRFT. (Apples has since acted as a manager for bands including Crystal Castles, Parallels, and Trust, and is now owner of Bambi’s. Sin would go on to collaborate with Will Munro on parties Seventh Heaven and Love Saves the Day. She now works in fashion direction.)

It was easy to see the Club 56 influence on scruffy spots like The Queenshead and 751, but it’s also evident that the club’s crowds and musical mix served as inspiration for larger venues like The Social and Wrongbar.

Wallace, who’d left Club 56 in 2002 and went on to do Evil Genius and other events at spots including The Boat and El Amigo, sees another angle.

“When The Drake opened [in February 2004], I began to notice a backlash against the open format, no dress-code, cheap-drinks ethos of Club 56. People wanted to be flashy again, exclusive again, show off a little and put up a velvet rope. I was sad for the development, but understood the cycle. It just meant we’d made an impression, and gave them something to react to.” (Wallace now lives with his family in New York City, where he’s a “stay-at-home dad to two great kids.”)

As for Club 56 itself, no one I spoke with was certain why it closed. There had been liquor-license suspensions, but a variety of theories exist as to why the venue’s doors were suddenly locked and slapped with a bailiff’s notice.

“There were a lot of rumours about the managers of the bar, but who knows what the real story was,” offers Luis Jacob. “I heard they never paid any rent, and just disappeared one day when they realized their luck had run out.” (Jacob’s own artistic career is flourishing. He also wrote an essay about Will Munro—who succumbed to brain cancer in 2010—that appears in the art-retrospective book Will Munro: History, Glamour, Magic. Munro’s life story is told in Army of Lovers, a newly published oral history written by The Grid’s own Sarah Liss.)

As for Club 56 owner Leslye himself, many say they’ve heard he was killed, but this cannot be confirmed.

“Rumour has it that Les got into a fight with his roommate, and was murdered getting out of the shower, but I never verified if that was a ‘Kensington urban legend,’” says McMahon, who bartended at Top o’ the Market after Club 56. “When you work for 13 years on-and-off in the Market, you hear a lot of them.” (She is now an assistant director and extras-casting assistant working in film and television.)

What is known is that 56 Kensington closed at the end of May 2004, and became known as Syp Lounge in January 2005. Peroxide and Expensive Shit continued there for a bit.

“It was good for a few parties, but it just wasn’t the same,” says Lucarini. “We had to bring in our own sound, and the fish tanks were gone. The new owner was also less daring when it came to flirting with over-capacity. I was moving to England that year anyway, so it felt like the right time to wind it down. We had a final [Expensive Shit] sendoff at The Boat.” (Lucarini is now a documentary filmmaker who contributes to the operation of Kensington’s Double Double Land alongside Dan Vila.)

Although its sign is still there, Syp Lounge was short-lived.

“Both Will Munro and, independently, Luca and I tried to take it over when it became available, but with no luck,” says Gordon. (In more recent years, he helped start Double Double Land, and now plays drums for Owen Pallett, has an electronic band called New Feelings, and works at Bambi’s.)

The building at 54-56 Kensington Avenue was recently advertised for sale, but that listing was put on hold last month. Given the ever-changing nature of Kensington Market, its future cannot be predicted.

Postscript: In response to the original Club 56 article published by The Grid, Club 56 staff member Nick Desando sent an email to confirm that owner “Leslie (Laszlo) was indeed killed. He died December 16, 2005. Leslie was a good friend. We, the staff at Club 56, often honour his memory.”

Thank you to participants Darcy Scott, Dougie Boom, Francesca Bungaro-Yemec, Franzisca Barczyk, Jaime Sin, Lara McMahon, Luca Lucarini, Luis Jacob, Mikey Apples, Mike Wallace, Rob Gordon, Rob Judges, as well as to Denise Balkissoon, Randreac, and Sarah Wayne.

1 Comment

All comments in the string below have been republished from their original appearance on The Grid website. We’re including the readers’ comments as they add to these Then & Now stories. We look forward to reading new comments here as well.

Steven

WOW! Flashbacks! Thanks Denise. 12:14 pm on January 7, 2014

Rachel

Thanks for this! This really took me back to that time. 10:27 am on November 20, 2013

Nostalgic

Great article. You guys should do a piece on “Day Jams” of the 90s. They were really popular amongst the asian (south and east) and west indian communities. Our parents wouldn’t let us go at night so some smart promoters and deejays got the idea to host parties during the school hours. So we all would skip classes at 12PM and attend these “Jams” at various venues namely, Spectrum on Victoria Park and Main St, Casablanca on Kennedy and Sheppard, Cylpso Hut, etc.. That was just in the east end, there were plenty of parties happening in west end (etobicoke, rexdale, missisauga) as well. In your research you will find Rusell Peters was involved in deejaying at these events too. Good Times. 2:44 pm on November 19, 2013

Rex

Super well-researched piece. Thanks! 1:55 pm on November 13, 2013

Andrew

Great parties. Cant believe it was that long ago. Seems like it wasn’t that far away, but the pictures look like its from a lifetime ago. making me feel old, but appreciative. 12:32 am on November 13, 2013

HairyToes

Never went there but looked like it had a good atmosphere just from the pictures. Ya gotta love the smaller venues, that’s why I miss the days of the warehouse parties. This place looks like something I would have enjoyed. Nice tribute mix. 6:40 pm on November 12, 2013

Ol Cee Pee

Definitely a highlight of my early/mid 20s. 9:04 pm on November 12, 2013