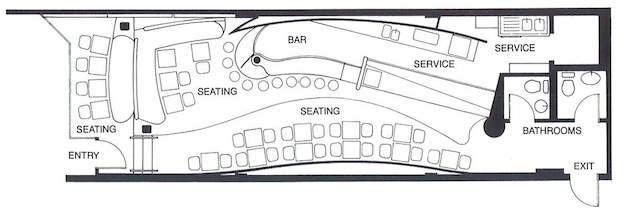

Boa Cafe, as it appeared in the Oct. 1991 edition of Interior Design magazine. Photo courtesy of INK Entertainment.

Article originally published May 23, 2013 by The Grid online (thegridto.com).

A special two-part edition of Denise Benson’s nightlife-history series begins with a trip back to the Yorkville venue that brought fine dining and club culture together—before going down in a hail of bullets.

BY: DENISE BENSON

Club: Boa Café, 25 Bellair

Years in operation: 1989-1998

History: This is a tale of two interconnected yet vastly different Toronto venues, each influential in its own way. For this article, I will be focussing on the first, Boa Café; the story of its second incarnation, Boa Redux, will be told in the next edition of Then & Now.

At the story’s centre lies Rony Hitti.

“I grew up in a family of restaurateurs and hoteliers, and was supposed to be the banker in the family,” says Hitti, who would instead become owner-operator of both Boas.

Hitti dutifully studied business finance and politics at York University, but also DJed steadily during the 1980s. He played a variety of Midtown-area clubs, and started his own DJ company, dubbed Earthquake in reference to the powerful Sensurround sound system created for the 1974 film of the same name.

“It used to shake movie theatres, and I bought one. I did pretty much all of the dances at York with that system.”

Banking didn’t work out for Hitti at the time, nor did dishwashing at his father’s restaurant. Instead, he studied culinary arts in Switzerland for a year. Upon returning, Hitti brainstormed a business plan with Charles Khabouth; the two Lebanese-Canadians had become friends as Hitti spent much time at Khabouth’s trendsetting Stilife nightclub.

“Charles and I were really close. We hung out, and traveled together. On a trip to Montreal, we went to a place called Lola’s Paradise. Lola’s was fine dining with that really cool Montreal vibe. We thought Toronto could use something like it. “Back then, last call was 1 a.m. and, inevitably at that time, everybody was looking for something to do. The only places to go were in Chinatown, for bad Chinese food, or Bemelmans on Bloor. We realized that the city needed a funky late-night dining spot that catered to a Stilife-like crowd.”

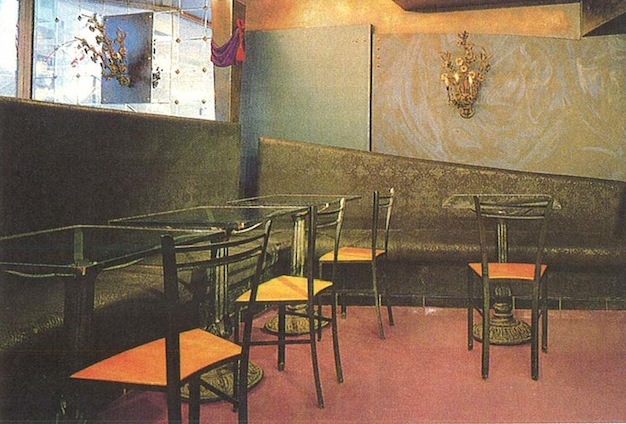

Initially 50/50 partners, the men envisioned a chic, but relaxed social spot that would serve quality food and drinks from noon until late night, five days a week. They looked to Yorkville for the location, and found 25 Bellair, formerly a daytime coffee shop. Five steps down from the sidewalk, but with a sizable window looking out at street level, the location was one long, narrow room that Hitti and Khabouth would greatly re-design.

“Yorkville was very much ’80s yuppie central,” Hitti recounts. “We wanted to bring Queen Street cool to Yorkville glam.”

Boa Café opened in October of 1989. There was nothing understated about it.

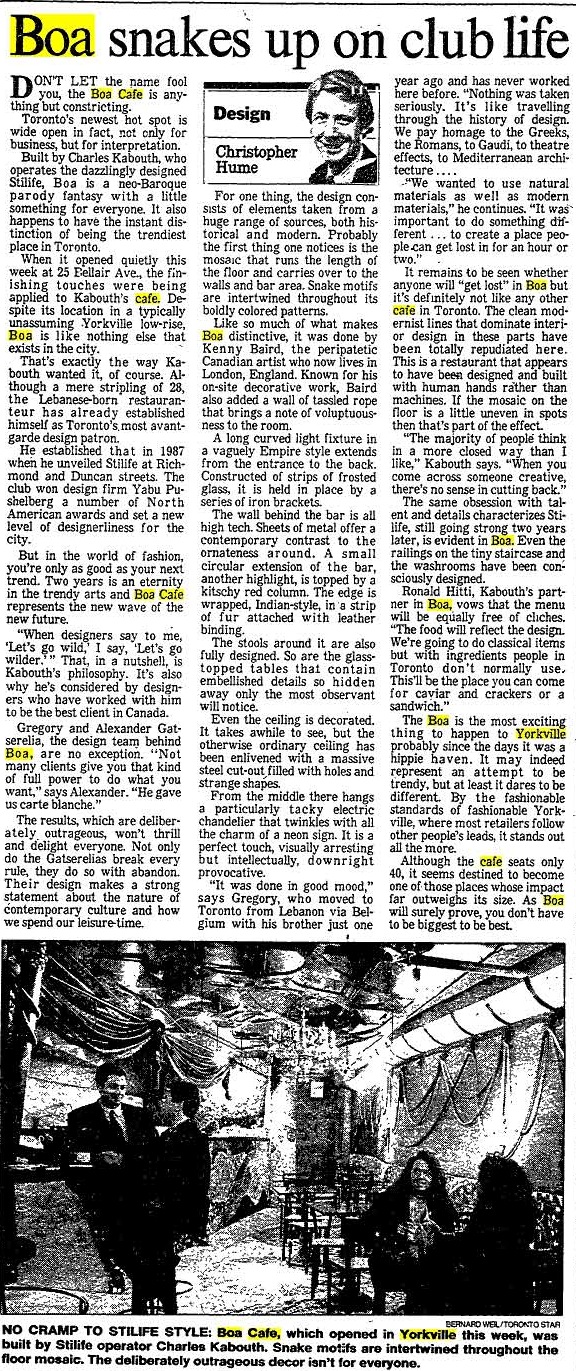

Why it was important: Although Boa Café only seated 40, it had “the instant distinction of being the trendiest place in Toronto,” wrote the Toronto Star’s Christopher Hume in an appreciative review dated October 28, 1989.

Boa became one of this city’s most coveted social spots thanks to a confluence of key elements and people. It certainly was an eye-popping location, whether one chose to hang out by day—magazines, chess, and backgammon were all on offer—or night.

“There was nothing like Boa in the city at that time,” says early staffer Marcos Durian, then also a production assistant in both film and still photography. “It was a small space with incredible design that drew the masses from early afternoon to the break of dawn. Boa may have been in Yorkville, but it was so un-Yorkville.”

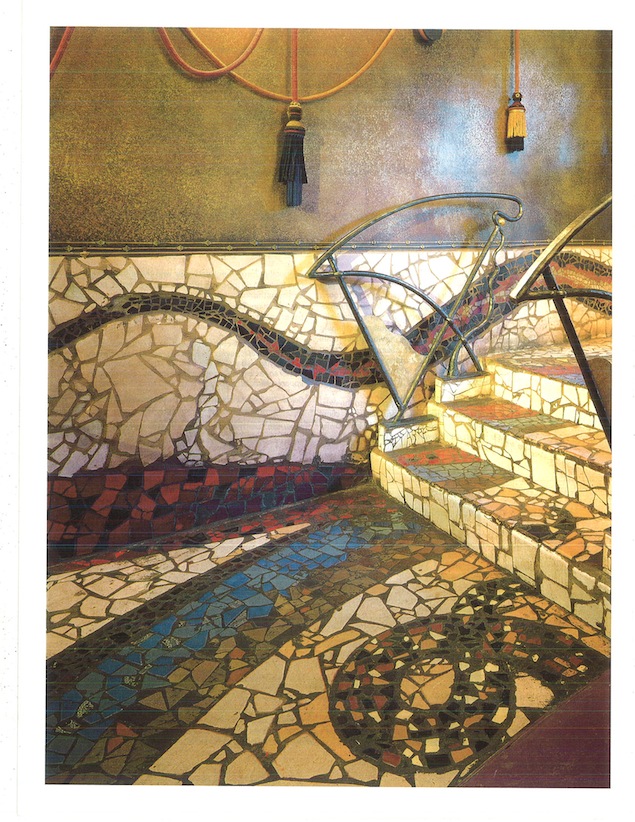

The aesthetic of Boa’s 1,200 square feet was largely imagined by Rony’s cousins Gregory and Alexander Gatserelia, together known as Gatserelia Design. Artist Kenny Baird, who had created installations and core elements for many clubs in the U.S. and Canada (including Khabouth’s Stilife), contributed Boa’s signature mosaic tiling, which covered much of the space.

“This was the ’80s, when it was the more detail the better,” chuckles Hitti. “Every single inch of it was designed, including the washrooms. The look of it was very whimsical; Gregory’s description was ‘It’s Antoni Gaudi meets Cocteau.’”

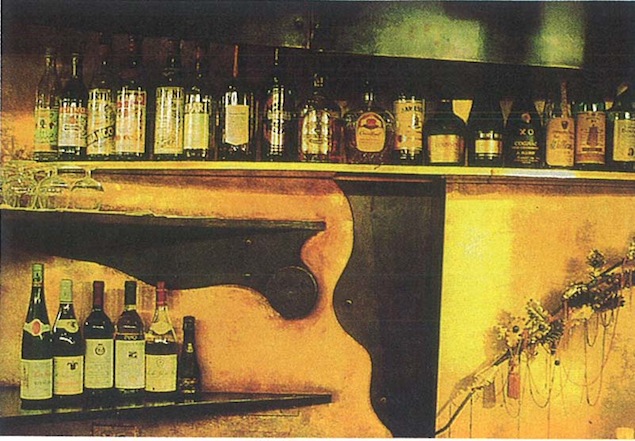

A bar ran the length of Boa’s room, with benches by the entrance and rows of tables filling the floor space.

“Boa packed a heavy visual punch,” says Durian. “It was dark and intimate, with warm lighting fixtures, specially treated sinuous metal, and a copper-bar top. An intricate, colourful, serpentine mosaic stretched across the floor and south wall from the front door to the restrooms in the back. A curved sheet-metal sculpture hung from the ceiling. The walls were a sponged dark brown with one gold-leaf wall that curved, like the contours of a snake behind the bar. Hence ‘Boa,’ as in the snake.”

But it wasn’t just Boa’s aesthetic details that attracted patrons; it was also the energy, talents, and youth of the Café’s early staff. Most were already friends, or became connected as patrons of Boa. Durian hung out before being hired as a waiter and bartender because his pal Thomas Koonings worked there in the same role. Both became super tight with Mark Bacci, a teenager who grew to become a star chef at Boa Café after Hitti showed him the ropes.

“Mark could not break an egg at the outset, but had an incredible palate,” says Hitti.

“I learned to cook from Rony in the early days,” agrees Bacci. “I was a natural at it, but he showed me a lot.”

Also central was Bassam “Sam” Nicolas, who had worked for Hitti’s parents for a decade prior to becoming Rony’s “right-hand man” and general manager at Boa. Hitti gives credit as well to “all-star waitresses” Rebecca Shafrir and Sacha Grierson, both of whom became part of the Boa team while still in university.

“Mostly, we didn’t feel like we were working,” says Shafrir by email, echoing a common sentiment. “It was rather like we were having fun in our own very edgy salon.”

All of these people personified Boa Café during its first year, a year that Hitti actually describes as “very difficult, business-wise” for himself and partner Khabouth.

“We lost our shirts, and Charles was starting to experience problems at Stilife because of Oceans [the club’s adjoined restaurant],” states Hitti. “The relationship went sour between the two of us, and we decided to go our separate ways.

“That’s when Boa became my baby. I made the food more dining, and less café-ish. I also decided to bring in some of the sound equipment from my house for the music, place a DJ behind the bar, and turn it into more of a party venue. It worked.”

No matter the hour, if Boa was open, so was its kitchen. Many describe the Café’s food in loving detail. (“There were chicken sandwiches with aioli to die for, the best tomato spaghetti by Mark Bacci, and a yellow plum tomato salad that no other fine dining restaurant could better,” writes Shafrir.)

“It was a small, eclectic menu with French, Italian, and Middle Eastern influences,” says Durian. “Mark Bacci was a one-man show, with two hot plates and a convection oven. I don’t know how we serviced all those people with the small work space and tools at our disposal.”

So too grew Boa’s focus on music. It had been integral from day one, as Hitti and DJs from Stilife provided funky mixtapes of soul, rare groove, deep disco, and early house, but the Café became more synonymous with its sounds after Hitti placed his turntables behind Boa’s bar.

“Boa was the first bar/restaurant in Toronto to incorporate a DJ at all times,” he claims.

At first, all of Boa’s staff took turns behind the decks, with Stilife DJs including Chris Klaodatos stepping in to play occasional late-night parties for which the tables and chairs would be pushed aside. Boa also hosted art exhibits, film-festival parties, fashion shows, and other events. The late night crowds began to swell.

“Boa was like the cool people’s secret,” recalls Shafrir, who left after her first summer to continue studies. (She is now a Trade Commissioner for the Government of Canada, working in Tel Aviv.)

“It was small, and from the street no one could guess it was the place to be,” she adds. “Yorkville was flashy and fake; Boa was the real deal. It had a crowd of regulars who kept it alive. It was a rather underground, artsy vibe.”

“Boa blew up at night, into this after-hours scene,” describes Bacci. “Everyone from the industry found themself at Boa. It was like this underground hub of what was cool in the city. It wasn’t a boozecan; people actually came to hang out, eat, and drink. Every top chef went, along with restaurant owners and workers. We would throw parties once a month that became an insane night, spilling out onto the streets of Bellair. Cops never bothered us—because they were customers, and because the food was so good that it just wasn’t that kind of place.

“Because of Boa, and the fact that everyone came there, a 17-year-old [like myself at the time] got reservations at top restaurants in the city on a last-minute call, or just by walking in.”

Kenny Baird’s signature mosaic tiling, as featured in the Oct. 1991 edition of Interior Design magazine.

Occasional parties gave rise to DJs on Boa’s decks Thursdays through Saturdays, when the Café would be open as late as 5 or 6 a.m. Boa became the late-night hangout for a huge range of people.

“It all happened very organically,” says Hitti. “We didn’t decide to become a boozecan; we were open late, serving food, and once in a while we’d have friends come in. They would get their ‘cold tea,’ and slowly but surely, the circle of friends became bigger and bigger. We basically became the hangout for everyone from politicians to crown attorneys, senior cops, very wealthy people, and at the same time even some of the biggest drug dealers in the city. The cross-section was amazing.”

“Boa was a kind of enigma where it wasn’t a club, a full-blown restaurant or a bar, yet it managed to be all these things and more in one night,” describes Durian. “Boa had a myriad of identities, which changed by the hour and by the clientele. You couldn’t cast half the people that came in.

“It was a melting pot, a mash up from every aspect and genre of nightlife in the city, especially on the weekends. You had the Stilife crowd, the Go-Go mob, everyone that worked at the clubs, bars, and restaurants. You had city brass, weekend warriors, pro athletes, hip-hop artists, the gays, the fashionistas, actors, producers, those looking for fame, and those just looking for a good time. You had nobodies, freaks and geeks, the rich and the not rich of all races. There was no end to the diversity that walked through that door.”

Durian, who left Boa in 1992 to study film in London and then New York (he’s now a Los Angeles-based director and cinematographer), mentions visits from the likes of Ben Kingsley, Lennox Lewis, Kid ‘n Play, and members of both the Toronto Maple Leafs and Blue Jays.

“When the Blue Jays won the World Series [in 1992, 1993], we were the place they came to celebrate,” confirms Hitti. “Boa was one of, if not the only place, you could find Galen Weston sitting adjacent to [later murdered] mob enforcer Eddie ‘Hurricane’ Melo, sitting next to a bevy a models, next to Queen Street types, next to other socialites and low lives all in perfect harmony. We operated on a face-and-attitude door policy: We either knew you, or you were cool enough to get in. It wasn’t about money. It wasn’t about being famous.” (Interior photos of Boa Cafe are rare; as Hitti admits, ”We didn’t allow cameras in there, for obvious reasons.”)

A young Susur Lee is reported to have been a Boa regular, as were owners of restaurants including Rodneyʼs Oyster House, Splendido, and Centro. A new generation of club and restaurant promoters and owners (or owners-to-be) also hung out, including the Assoon brothers (Twilight Zone), Edney Hendrickson (Octopus Lounge), and Leslie Ng and Byron Dill (Kubo DX and more).

Dill, in fact, was such a regular at Boa, he later joined the staff as a bartender and event promoter.

“Byron brought that very Queen Streetish crowd vibe,” Hitti admits. “He and his friends helped make Boa Café what it was in a lot of ways.”

Bacci, in turn, credits Hitti with connecting scenes and communities.

“Yorkville was dud central at the time, [full of] dated places,” says Bacci. “It was like what Rony did in its own strange way harkened back to the Yorkville of the 1960s, like when Joso’s was just a place to drink. Boa somehow became the centre of the universe for the downtown scene. You felt like you were a part of something [that was] almost before its time for the city.”

Like friends Durian and Thomas Koonings, Bacci left Boa in the early ’90s. He moved on to cook at restaurants including Left Bank and 80 Scollard, before re-locating to New York for film school. He’s made his way as a U.S.-based actor, writer, and director ever since, maintaining ties to both Boa and Toronto. And though he and his family split time between L.A. and Hawaii, Bacci co-owns a number of Toronto restaurants, including the Lil Baci locations. (Durian has served as Director of Photography on all of Bacci’s films.)

Food remained very much a focus at Boa long after Bacci’s departure, but its DJs and late-night dancing continued to grow in popularity. After DJ Chris Klaodatos left as resident, Energy 108’s DJ Fran stepped in as Boa’s main weekend spinner from 1993 to 1996, with DJ Radamés Nieves blending Latin and Afro beats on Thursdays and occasional Fridays.

For a six-month-period of Saturdays in 1996, Fran was also joined by Hedley Jones a.k.a. Deadly Hedley, a CFNY and Klub Max alumni who, by then, also worked for Energy 108. Fran and Hedley’s popular live-to-air from Boa Café ended abruptly when Fran was found dead one Sunday morning, after he’d left the party. (Jones is now based in Los Angeles where he works as a photographer.)

“In a way, a bit of the spirit of Boa went out with Fran,” says Hitti. “It was a very close-knit group.”

The Boa bar, as featured in the Oct. 1991 edition of Interior Design magazine. Image courtesy of INK Entertainment.

What happened to it: By 1996, Boa Café was so busy that a second room was added, doubling the venue’s square footage and creating a designated dancefloor. Many hundreds of people would come through on weekends, packed in “like sardines,” according to Hitti.

“If one person danced, everybody danced. People would dance on tables and chairs, they’d dance on the bar, there were people having sex. It was absolute debauchery.”

That said, Boa didn’t receive a lot of police attention.

“I would get raided twice a year, and the charges would disappear,” shares Hitti. “Everybody thought that I was paying off half the city. I never paid anyone a single dime, but I kept good relations with everybody, and I guess people thought, ‘Why not? The place doesn’t have any problems.’ There was no overt drug dealing, everybody was having fun, and it was a discreet venue in Yorkville. It kind of took on a life of its own.”

But Hitti acknowledges, “It got to the point where the place was so busy that eventually this was its downfall.

“Literally, people would get off a plane at 1 a.m., ask where they could get a drink, and taxi drivers would bring them down. People would show up at the door, and many would be told they could not come in. We had just one doorman, Larry Trump; he could handle all those crowds by himself.

“One night in 1996, Larry told some guys they could not come in. I was called over, and said the same. One of them looked at me and said, ‘I’ll come back and spray the place.’ He went to his car in the parking lot, pulled out a machine gun, and shot seven bullets through the window. We had two of those incidents, and that’s largely what motivated me not to renew the lease in the end. Both times when it happened, the place was packed and bullets literally flew over everybody’s heads. Nobody got hurt. Twice lucky, we weren’t going to risk a third time.”

By 1998, when Hitti’s lease at 25 Bellair came up for renewal, he also owned businesses including Brasserie Zola (“a very bourgeois French restaurant”), Winston’s (“probably the highest-rated fine-dining restaurant in the city [at the time]”), and Turkish Bath, the member’s-only nightclub beneath it.

“My name was associated with being a chef, and owner of fine dining establishments,” Hitti concludes. “The last thing I wanted was my name in the newspaper associated with a shooting.” The lower level of 25 Bellair is now home to Vaticano Restaurant.

The story of Boa continues in the next edition of Then & Now, when I revisit the club’s resurrection in the early 2000s as after-hours dance club Boa Redux on Spadina.

Thank-you to Boa Café participants Mark Bacci, Marcos Durian, Rebecca Shafrir, and Rony Hitti, as well as to Hedley Jones and Thomas Koonings.

No Comments