Click through the photo gallery for many more moments and memories from Roxy Blu.

The original Then & Now: Roxy Blu article was published September 21, 2011 by The GridTO.com. That story launched Then & Now: Toronto Nightlife History, originally envisioned as a series of brief articles devoted to defunct but influential Toronto music venues. As Then & Now’s popularity and reach expanded, it became increasingly important to include more voices in each story. As a result, the earliest stories for The Grid were entirely rewritten for Then & Now in book format. This expanded history of Roxy Blu was written in March 2015, and was exclusively available in the Then & Now book until this time.

Roxy Blu was home to the soulful side of Toronto’s dance-music underground, and with its four rooms, welcoming atmosphere, and loyal community of followers, Roxy fostered and supported a culture where parties and promoters could create without compromise.

By: DENISE BENSON

Club: Roxy Blu, 12 Brant

Years in operation: 1998 – 2005

History: Although it would come to be known as a community-minded hotbed for soulful house and other underground sounds, Roxy Blu was decidedly different than any other club projects owner Amar Singh had ever touched.

In the early to mid-’90s, he and Bill Kourbetis worked together as B&A, promoting events at ritzy, popular nightclubs like Stilife, Skorpio, Orchid, and Exit II Eden. They parted as co- promoters when Singh opened a club called Bauhaus at 31 Mercer. Known for its see-and- be-seen Martini Mondays, well-dressed crowds, and sleek design, Bauhaus was successful, but Singh walked away six months after opening.

“I just wasn’t there mentally,” he says; “I knew I wanted to be in the industry, but I had to make some changes. I sold my shares for pennies on the dollar.”

Singh took another approach for his next venue.

“I didn’t want to do what I did with Bauhaus, which was spend so much on renovations. The clubs that I used to go to, that I really, really loved, were not the club I created in Bauhaus. The club I created was the kind I used to promote—the Orchids and so on, all pretty and nice. To this day, the clubs I loved going to the most were Tazmanian Ballroom—anything Johnny K really; he was my mentor—and of course Twilight Zone, as well as Le Tube. Those are the places, along with some spots in New York, that really inspired me in my next venture, which became Roxy Blu.”

Singh stumbled upon the 10,000-square-foot building at 12 Brant while out on his bicycle. He’d been looking in the area of King west of Spadina, as it was off the beaten path and rents were cheaper. At the time, the building’s lower level housed Bodega Manila, a Filipino restaurant run by the owner’s wife, while the upstairs acted as storage for the rattan furniture the couple imported.

Singh spoke casually with the owner while touring the space. He didn’t see potential for a nightclub at first.

“Then I tripped on the carpet, and noticed that under it was a beautiful hardwood floor.”

Upon learning the entire main level had hardwood, Singh asked more questions. He also discovered the building was licensed throughout, a huge boon in a city where new liquor permits can be difficult to come by. Multiple conversations and many months later, Singh had the go-ahead to rent the building and then, eventually, the silent partner and small business loan that enabled him to do so.

He relied on the help of friends to get Roxy Blu off the ground. Jennifer Pratt designed its logo and rooms.

“When I invited Jennifer to design the club, I told her, ‘We’re looking at $10,000 to get the space going.’ She said, ‘Amar, you can’t paint this place for $10,000. It’s going to cost more than that!’ I said, ‘You don’t understand; it’s $10,000 for paint and furniture.’”

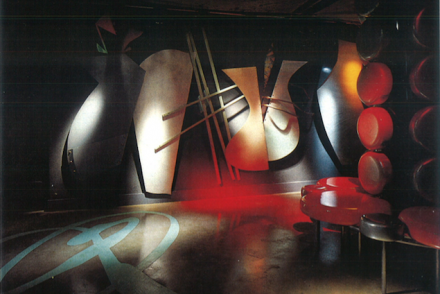

Budget dictated that Roxy was adorned with discount paint, thrift store furniture, and strategically placed bits of fabric, but its comfy décor and related warm vibe would become a draw. The club opened in September, 1998.

Roxy entrance. Photo courtesy of Denis Scher-McDowall.

Why it was important: “A friend once said to me that the reason Roxy Blu became such a success was that it was built with love,” shares Singh. “That’s true. Even on opening day, a tonne of my friends painted and helped clean because I had no money.”

Singh also hired a number of friends, including Denis Scher-McDowall, who worked as a Roxy bartender before becoming manager. She recalls that the club’s dark, unassuming entrance and less-than-obvious location lent a warehouse feel.

“Roxy Blu was a huge, two-storey building that had a sort of warehouse look to the outside, but once you stepped inside, it was an eclectic mix of your grandma’s living room with the coolest vibe you could imagine,” Scher-McDowall describes.

“When you first came in, there was the lounge on the right, which had three plush semi- private rooms, lots of fabric, lamps, a DJ booth, small bar, and a drummer. It was more of an area to chill out and listen to some great music. The main room had two bars, a DJ booth, lots of space in the middle for dancing, and seating around the perimeter.”

“We opened it up one room at a time,” explains Singh. “Then people who came early didn’t feel consumed by the big space. Even if there were only a few people in that room, it was nice and warm.”

The main room had low ceilings, a long main bar, and plenty of ambiance.

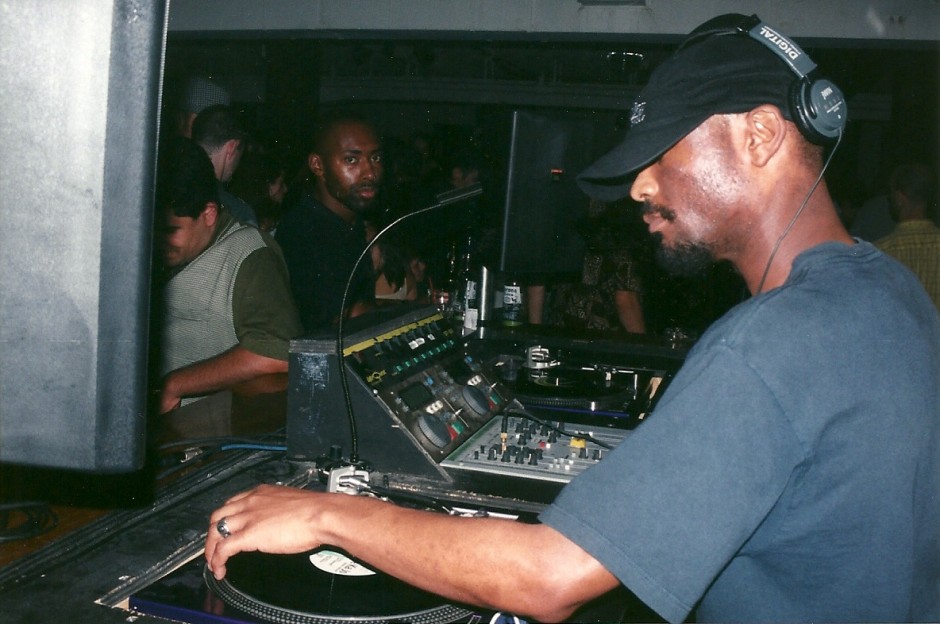

“The ceiling height might have been 12 feet, with attached pin spots and oscillating lights that were really dynamic in the way they washed the walls and dancefloor,” recalls Winston Thompson, Roxy’s Saturday night resident DJ for the club’s entire history. “It had a phenomenal wood floor and a beefy JBL sound system. The system, coupled with ceiling height, décor, floor, and the warm feel of vinyl records, made for incredible acoustics.

“If you wanted to dance and sweat, you were in the main room; if you wanted to chill and conversate, you could slip into the lounge, aka the Parlour.”

To those who had frequented the many speaks and warehouse parties devoted to house music in late ’80s through early ’90s Toronto, Roxy Blu’s natural character was obvious. Singh didn’t initially see it this way.

“The problem was that up until that point, all I really knew was the European crowd—big on drinking, but they loved to go to pretty places,” says Singh. “I was comfortable in those places, and also comfortable in underground spots, and was convinced that everyone was like me in this way. I thought my Euro crowd would like Roxy, but I didn’t really have ties to the underground crowd.

“Opening night was packed, but those people never came back. Three or four months in, I was pulling my hair out thinking it was going to be a disaster. Then a guy named Justin [Martin, of alienInFlux] came to me and said he wanted to book in an act called Kruder & Dorfmeister. I didn’t know them at all. I wasn’t into the music. I’m a rock and roll guy.”

Martin brought Kruder & Dorfmeister on a Friday early in 1999. It was a packed, incredible event—the kind of night where those of us in the room knew we were at something special.

“That event opened up the floodgates,” states Singh. “Everyone then came to me saying, ‘Let’s do a Friday.’ If it wasn’t for Justin, I don’t think that would have happened.”

Soon after, promoters including Hot Stepper and the Movement DJ collective started producing monthlies. Roxy Blu became the place to go, for different crowds, on both weekend nights.

“The rotation of parties on Fridays was the real deal, with Movement, Garage 416, 52inc., milk, Solid Garage, and more,” says DJ Paul E. Lopes, who played at most of these events, as well as Hot Stepper’s Bump N’ Hustle, over the years. “You didn’t have to know what the party was about or who was hosting or spinning—it was guaranteed to be good.

“Roxy Blu really was the ideal space for us. All the regular promoters were on the soulful end of club music, so it attracted a more casual, music-loving, dancing crowd. The sound system was great, both for ‘club’ records and the old disco, soul, and jazz that got spun a lot there too. The hardwood floor attracted the best dancers, and they helped give the room a great vibe.”

Also appealing was the fact that Roxy had four rooms, including two on the lower level, called Foundation until renamed Surface. Within the club’s first year, each room had its own DJ booth and sound system, which could also be linked as one. Some nights there were separate parties on each floor, while on other occasions promoters booked DJs in each room.

This story is as much about the core events held at Roxy Blu as it is about the club itself.

Movement was one of the first parties to fill all four rooms on a monthly basis. The five men of Movement—Aki Abe, Jason Palma, John Kong, Nav Sangha (aka deejay Nav), and Simon Warwick (aka A Man Called Warwick)—had an enormous impact on Toronto’s underground music scene after they came together in 1998.

“We were tired of being marginalized to lounges or chill-out rooms,” explains Sangha of the impetus to join forces. “We all knew that people were playing the soul, funk, Latin, Brazilian, and jazz records we were into to much larger crowds in dance clubs around the world, and wanted to make that happen in Toronto. We’d all tried to achieve this on our own, but it took the five of us to gain that critical mass.”

“As DJs, we had quite dissimilar backgrounds,” adds Abe. “My first love was house music; I grew up playing the warehouse scene from ’89 to ’94. I was also Eugene’s first employee at Play De Record in 1991, when I was 19, and that’s where I met John and Jason, as they were regulars. I can’t think of anyone as obsessive about music as they were. Nav and Simon were pretty infamous in the collector’s scene; Nav was the skateboarding free jazz guy, and Simon just had records no one had ever heard of.”

Prior to Movement, Palma also worked at Play de Record and hosted radio show Higher Ground, Kong played in lounges and bars around the city, and Warwick and Nav did a funk, jazz, and Latin club night together called Tempo. Sangha also worked at two record shops, Driftwood Music and Rotate This. All five were devoted diggers.

“We all were DJs, but first and foremost we were passionate vinyl collectors, competing to find albums we’d never heard before,” emphasizes Abe. “It was a healthy competition, which evidently translated into a good party.”

They made this discovery after combining their networks and different skill sets to launch Movement in the back room of The Rivoli in late 1998.

“By the third monthly party, we had a line-up as long as Ikea on Sunday afternoons,” states Abe. “We moved it to Roxy Blu as a Friday monthly, which gave us a capacity of 1,400, and we maximized every sweaty inch of that space, not according to fire code.

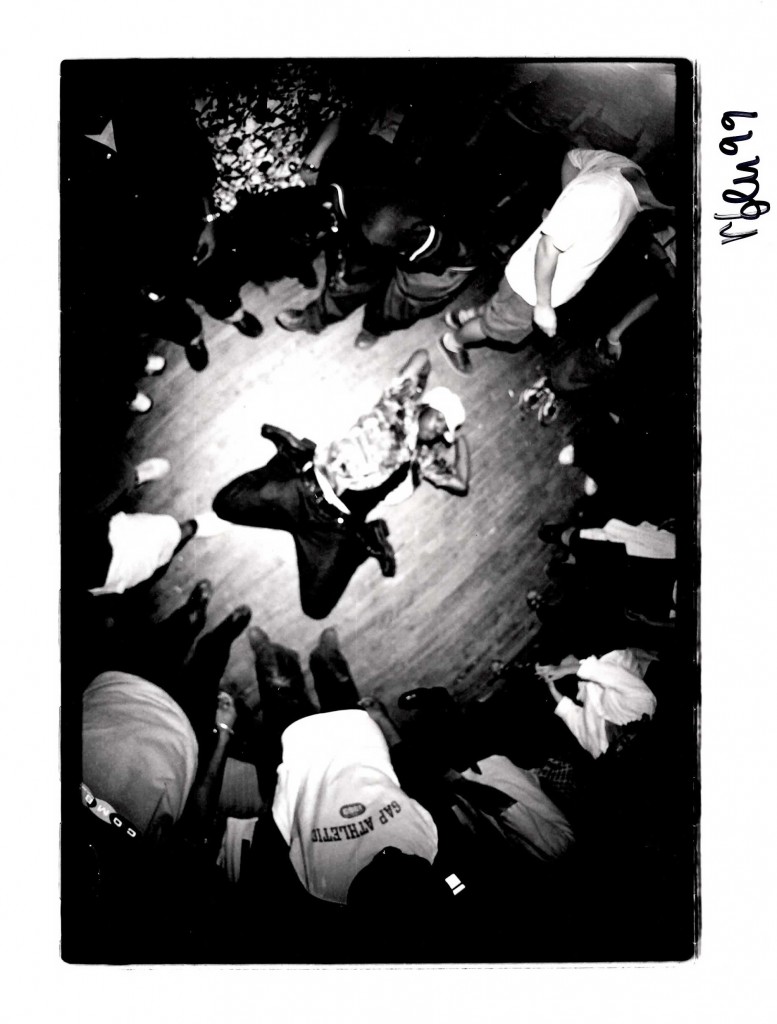

“Roxy was everything you didn’t want in a nightclub, so it was perfect for us. Old wood floors were covered by Simon’s talcum powder, which originally was to help his knees when he got down on the dancefloor. Simon is a great dancer. Sixteen booming bass bins, which people would sometimes dance on, were scattered in the middle of the floor. We also had the best doorman in the city, Dan Toner, who resolved any issues with a huge smile.”

Walking into Movement was like entering another dimension. You never knew what you might hear, who you could end up dancing with, or what you might see. It wasn’t utopia, but it came damn close at times.

“Movement was about dance music, but not in the conventional four-on-the-floor nightclub sense,” describes Sangha. “It included the evolution of all forms of dance music, from folkloric African, Latin, Brazilian, Middle Eastern, and Indian music to jazz, blues, reggae, soul, rock, funk, disco, drum and bass, hip-hop, techno, and house. Basically, anything rhythmic could potentially work, yet there was always an underlying vibe that made a track a Movement record. It was really organic.

“We all took a lot of chances with the programming. The crowd made the anthems; they were really hungry for new music.”

The crowd’s appetite was fed not only by the Movement collective, but also by the DJs they booked. Roxy Blu’s capacity allowed them the budget to bring in collectors from other countries, including DJs and producers such as Gilles Peterson, Jazzanova, Kyoto Jazz Massive, Rainer Trüby, Snowboy, Russ Dewbury, Manu Boubli, and Nicola Conte.

“One Movement, the airline lost Gilles Peterson’s records and he ended up playing John’s without missing a beat,” shares Abe. “Gilles was happy enough to come back several times.

“Another memorable night was when Keb Darge came; we didn’t understand why he wanted a bucket in the DJ booth. Later, we saw him relieving himself while playing his thousand dollar singles since most of them are only three minutes long.

“Most of these guys were master selectors; they never cared about mixing techniques, but the night always flowed seamlessly,” Abe adds. “It was a treat to have other collectors spin their best. Believe me, we were the first ones trainspotting by the turntable.”

Roxy’s rooms also allowed Movement to book local and global DJs who played house, tech, and other electronic sounds that the core crew rarely touched. Abe mentions Nick Holder, DJ Stuart, Theo Parrish, Frankie Valentine, Faze Action, and Idjut Boys. Anything went, to some degree.

“We each had our own distinctive sound when it came to classic and old school records, but we would often fight over who would play the hot, new breaking tracks at a party,” says Sangha. “Except for Warwick; he always did his own thing. Given the opportunity, he would come behind the decks at peak time and drop something insane, like the string section introduction to a ’70s Indian soundtrack or a wildly obscure West African highlife record. He seriously did not give a fuck. I’m pretty certain he still doesn’t, which is what makes him so amazing and unique as a DJ.

“We really pushed each other to excel and break boundaries. I think that’s what helped to create a lot of the magic of Movement. We were all complete and utter record maniacs, and the music played truly reflected that.”

To illustrate, I ask Abe which songs he especially associates with each of his Movement DJ partners.

“John Kong: Lemuria’s ‘Hunk of Heaven’; Jason Palma: Roberto Roena’s ‘Que Se Sepa’; Nav: Buari’s ‘Advice From Father’; Simon Warwick: Charly Antolini’s ‘Atomic Drums’; and for myself: Alice Babs’ ‘Been To Canaan.’

“There was no YouTube, eBay, or cameras on phones at the time, so it was very difficult to track down most of these records,” reminds Abe, who has made it his living to find and sell vintage vinyl since opening Cosmos Records in early ’98.

“I don’t want to overreach, but the times at Roxy Blu were unequivocally spectacular, and quite unique in Toronto. We were able to showcase an array of music, generally played only in underground venues, to a mass audience. It’s a dream come true for most DJs, and we did it all on vinyl!”

Movement was a monthly fixture in Roxy’s calendar for most of the venue’s lifespan. Another Friday was devoted to Garage 416, produced by brothers Pedro and Carlos Mondesir of Hot Stepper Productions.

Pedro had started Garage 416 in September of 1998 with the goal of uniting a splintered soulful house scene. The party quickly outgrew its original 300-capacity home of Granite Lounge on Richmond West, as well as other venues including Bauhaus. The first Garage 416 at Roxy took place in June 1999 and featured the Toronto debut of New York deep-house DJ/producer Joe Claussell of Body & Soul.

“It took months to convince Joe’s team to have him play the party,” recalls Pedro. “That gig allowed us to further grow Garage 416 and to establish ourselves at Roxy for other events.”

This included Tony Humphries’ return to Toronto in September 2000 for the Garage 416 two-year anniversary.

“Like Claussell, it took a lot of convincing for Tony to accept my invitation, but for different reasons,” says Pedro. “The rumour was that Tony had ‘written-off’ Toronto. When I asked why, he said he felt that the city did not appreciate his style of DJing. After numerous calls and providing him with a list of DJs who had headlined Garage 416, I convinced him. The event attracted 1,500 people and was the largest Garage 416 at Roxy Blu.”

Between 1999 and 2003, Garage 416 also hosted more than 45 Toronto DJs—including Peter & Tyrone, Nick Holder, Ray Prasad, Mitch Winthrop, Kevin Williams, and Jason Palma—alongside resident crew Blueprint (Jason Klaps, Alan Lo, and Mike K). Pedro also DJed, as Moreno, from 2001.

Garage 416’s impressive array of international house headliners included the first Toronto appearances by Norman Jay, Danny Krivit, Timmy Regisford, DJ Spen, Mateo & Matos, Jerome Sydenham, E-Man, Lady Alma, Kaskade, Ame, Dennis Ferrer, and others.

“Dennis had never played outside of New York before, and I was hesitant to book him initially,” admits Pedro. “I only booked DJs with true DJ skills to headline and never cared to book someone simply because they were a popular producer.

“I was a huge fan of Dennis’ music but had never heard him DJ. However, Jerome Sydenham, who had played Garage 416 several times, highly recommended him. The risk paid off; Dennis rocked the night [in September 2001], and I booked him to play again in May.”

Carlos points to François K’s first appearance at Garage 416, in June 2001, as another stand out.

“The power went out in the middle of his set. We had to call Amar’s father to come and fix it, that’s how DIY Roxy was. He did, and the night continued. People didn’t leave!”

Roxy Blu was a bastion of garage and house at a time when Toronto’s rave scene had exploded, and most clubs devoted to dance music either featured big room, harder-edged sounds or commercial hits. There was some audience crossover with clubs like Industry and The Living Room, but Roxy promoters consistently took us to the deep end.

Junior Palmer had launched his PhatBlackPussyKat parties as a Saturday after-hours at 488 Yonge in 1998. With core resident DJs Joe Rizla, Kaje, and Trini, the party ran for four months before moving to Foundation, below Roxy Blu.

“PhatBlackPussyKat was created to introduce more people to the deep, soulful sound of house music, which was what I grew up listening to at the Twilight Zone,” says Palmer.

“The thing that attracted me to Roxy at first was that it felt like you were in someone’s living room. I believe the vibe was so amazing there because everyone felt like they were at a house party with family and friends. No one cared about what someone was wearing. There was no posing or attitude.”

Palmer presented parties on both floors of Roxy over time. He booked a lot of local and North American talents, with one of his standouts being a night in January 2004 when he brought Byron Stingily and Frankie Feliciano in alongside Peter & Tyrone, Nick Holder, Angel & Cullen, and John Kumahara.

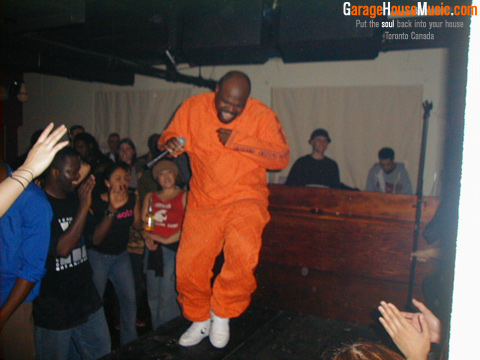

Byron Stingily presented by PhatBlackPussyKat. Photo by GarageHouseMusic.com, courtesy of Junior Palmer.

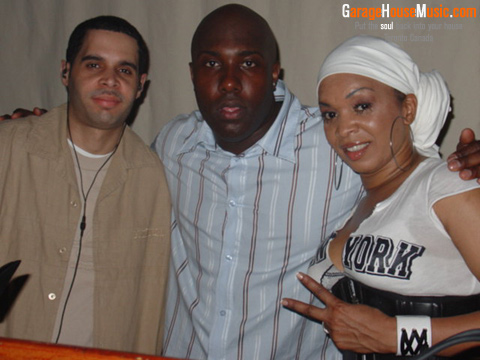

Frankie Feliciano (L), Junior Palmer, Barbara Tucker at PBPK. Photo by GarageHouseMusic.com, courtesy of Junior Palmer.

“The energy in the room was electric. There was a line-up down the laneway at 10 p.m., before the doors were even open.”

The Groove Institute DJs—Yogi, Mark, and Anand—played often, including at PhatBlack- PussyKat. As United Soul, the trio also produced and promoted the Solid Garage monthly on Fridays, spinning gospel-infused classics like Kenny Bobien’s “I Shall Not Be Moved,” Donna Allen’s “He Is The Joy,” and Jasper St. Company’s “Till I found U.”

No matter who was in on a Friday, Roxy-goers were guaranteed an eclectic mix of music and people. Promoters worked together to develop the schedule, and often there was collaboration.

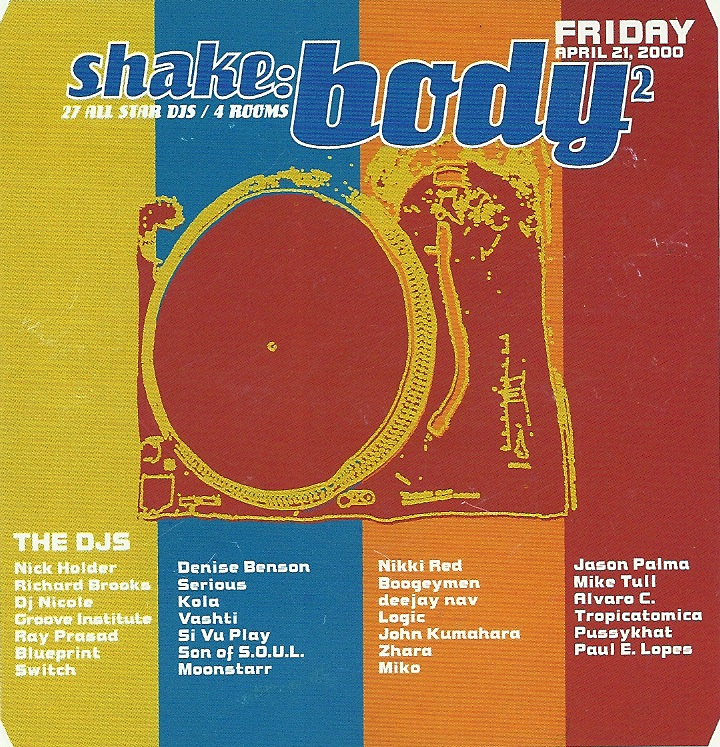

The women behind College Street café and bar 52 inc., Kate Cassidy and Amy Katz, presented many unique events at Roxy, including a sold-out co-presentation of spoken word artist Ursula Rucker and massive fundraising parties dubbed Shake:Body, which featured close to 30 Toronto DJs and performers. 52 inc. also went all-out for their epic DJ Battles.

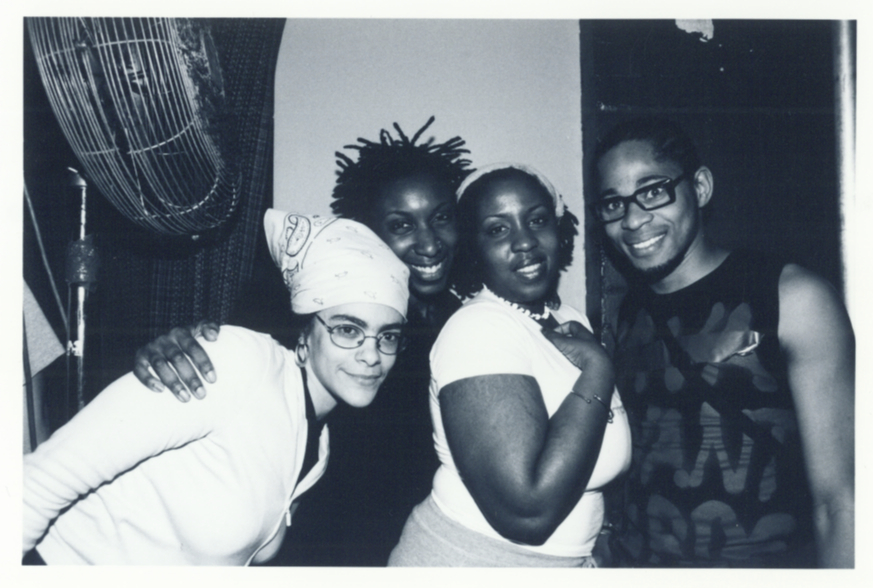

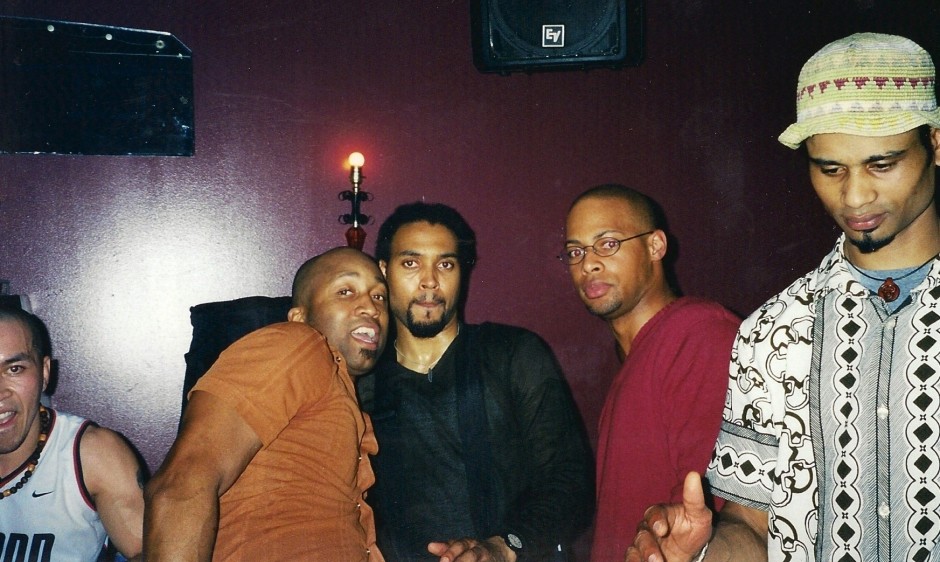

Ursula Rucker (L), Karen Augustine, Jemeni, and Shafiq presented by 52inc. Photo courtesy of Kate Cassidy.

“Doing those Battles was the stand out for me,” says Paul E. Lopes, who acted as referee. “The 52 inc. ladies rented crazy movie props for the night, including a huge trophy and life-sized side of beef. We wore boxing gloves and ref shirts, and everyone got a whistle and towel at the door. The energy was off the chart!”

Lopes also DJed at a number of events produced by milk. The crew, anchored by promoter Izzy Shqueir and resident DJs Felix and Gani, developed dozens of parties at Roxy between 1999 and 2003. Inventive guests like Howie B. and Bobbito were imported to play alongside locals including Movement’s Jason Palma, reggae selector Chris Harper, house producer Abacus, and Mod Club duo Bobbi Guy and Mark Holmes. Musicians such as sitar player Yoshi and soul-jazz star Ivana Santilli were part of milk.’s creative mix, as were visual artists including Eddie Figueroa and Andres Correa.

At Roxy, milk. also began to collaborate with promoters RNB, then the duo of Richard Brooks and Natalie Brown. RNB produced elaborate events that stood out, both because their promotion was exceptionally well designed, and they blurred the boundaries between deep house and atmospheric tech. Brooks DJed alongside fellow locals like Ali Black, Kenny Glasgow, Joe Rizla, Trini, and Abacus, and presented DJ/producers not frequently found on Toronto lineups at the time, including Kerri Chandler, Ron Trent, Glenn Underground, Rasoul, Mark Grant, and Alton Miller.

“Roxy was disconnected from the club scene, and catered to a deep and soulful vibe that was it at the time,” enthuses DJ/producer Brooks. “Fridays brought out a unique crowd, with many recognizable and friendly faces. The Friday parties had a lot of overlap.”

“The Friday night crews all attended each other’s events,” says Carlos Mondesir. “That’s how interesting it was; even though you’d done your gigs there, you still went back to the same space because other people were doing compelling things. The competition to impress with novel themes or great talent was very strong. We also knew that the market we were creating there brought in acts that were not viable in most cities in North America.”

Roxy Blu provided a home base, and an ideally sized space, for Toronto’s underground music communities to thrive.

“Interestingly,” comments Carlos, “I don’t think any of the major parties there actually started in Roxy Blu, so the ideas and people were already bubbling, but they were certainly amplified beyond everyone’s expectations in that space.

“Because of the frequency of different events, the certainty of a good turnout, and with at least three DJ stations, the promoters had the opportunity to book more local DJs. The various parties created a big momentum; a couple hundred people would show up not having any idea of who was playing, but they knew what kind of vibe to expect and that they would likely hear artists you couldn’t find in any other club in town. Or in most other towns, actually.”

Clockwise from bottom: Gilles Peterson, Rob Gallagher, Paul E Lopes presented by Hot Stepper Productions. Photo courtesy of Hot Stepper.

That large pool of Roxy regulars allowed promoters and DJs to take chances. It was like a positive feedback loop that resulted in a broad, loose knit community that was passionate about music and dancing. The starting point was the club itself.

“As soon as you walked in, you could feel that it was different from other clubs, more earthy, more genuinely about a type of music that drew you in and made you lose yourself,” recalls Scher-McDowall. “It was like a huge love-in, and everyone was welcomed and accepted.”

“The mix of people that came to Roxy was special,” agrees Junior Palmer; “It was a breed that all wanted the same thing—to hear great music, be around great people, and be free of judgement related to race, sex, style, or background. Everyone knew each other; it was like a family.”

“The crowd was mixed in every way, cool but unpretentious,” adds Mondesir. “We take for granted many things in Toronto, and one of them is diversity. Many clubs and parties don’t reflect it; ours definitely do, and Roxy definitely did. I always maintain that the crowd is as big a draw as anything else, and the flow of people, because of Roxy’s layout, added adventure.”

Adventure also came in the form of the people themselves.

Shaun Lowcock got involved in Roxy Blu before it opened, after meeting Singh in a course. A former currency trader, Lowcock had both business and bar experience. He helped connect Singh with investors, and worked as a Roxy manager from 1998 to 2003. Lowcock could not only fix almost anything on the fly, he was also smoothly social. He even met his wife on a Friday night.

“Working Fridays was a joy ’cause I got to meet and groove to my favorite DJs,” says Lowcock. “People were there for the music, and they were a great crowd considering there were up to two thousand some nights!”

Lowcock rattles off a long and incredibly varied list of faces familiar to him from Roxy nights. He mentions regulars who were in music, film, fashion, food, and design, including Nelly Furtado, John Hurt, Cheryl Gushue, Leslie Ng, Byron Dill, Corinne Lee, Johanna Black, and Jason Priestly, who sometimes arrived with Roots Canada co-founder Michael Budman.

“One time Michael showed up with Robbie Robertson. We found a quiet corner and shared a joint—perks of the job! NHL players Eric Lindros and Mats Sundin came a few times. The Hell’s Angels also showed up a few times and were some of the nicest people. [Porn star and producer] Jill Kelly was there one night. I had a great time chatting with her.”

Singh now realizes that the massive mix of humanity at Roxy was as it should be.

“Any business has its own personality, and if you get in the way of that personality, you’ll fail. The personality of the club dictated who the clientele was going to be. In the end, we got a nice hybrid; Fridays were the hardcore ‘Let’s dance’ people, while Saturdays ended up being a crowd that was somewhere in the middle of the Euro and the underground.”

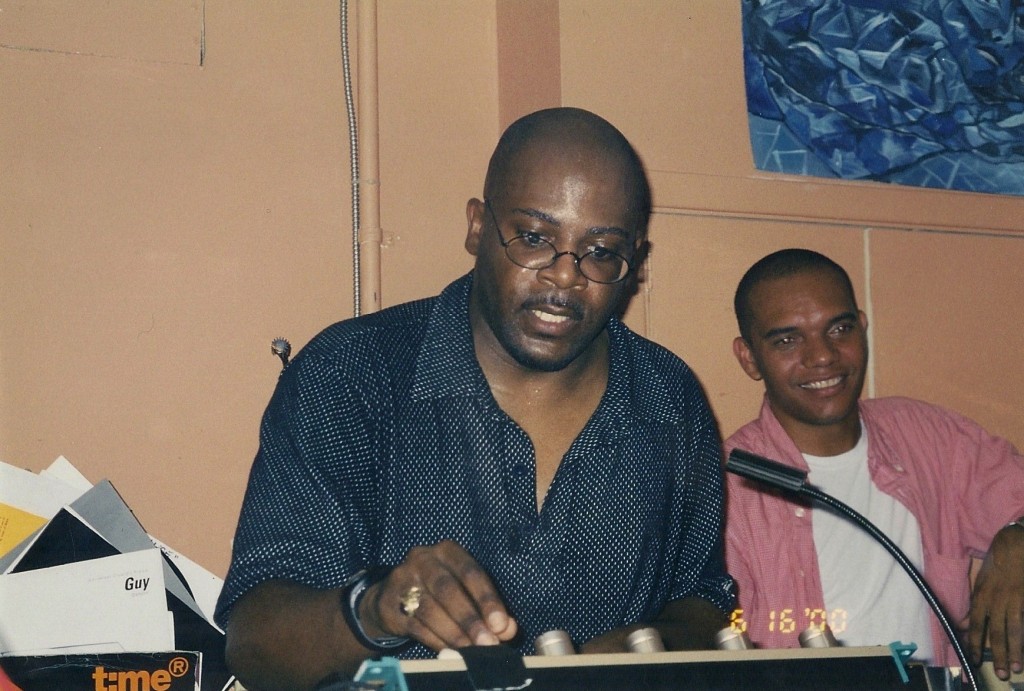

Who else played/worked there: “Saturday nights were totally different than Fridays, as the crowd was not the downtown underground scene, but people definitely knew their music or wanted stuff that was not being played on radio,” describes resident DJ Winston Thompson, who had also played at clubs ranging from Bauhaus to the early incarnation of Guvernment.

Thompson includes songs like Armand Van Helden’s “You Don’t Even Know Me,” Celeda’s “Be Yourself,” Jon Cutler’s “It’s Yours,” and “Fly Life” by Basement Jaxx as among his anthems of the time.

“If people were at Roxy on a Saturday, they did not want cookie cutter Euro music. We were able to play great after-hours sounding tracks, but in prime time, with a splash of bigger songs. Tracks like Junior Vasquez’ “X,” which always made the hair on the back of my neck stand up when played on that sound system, were mixed with some of the bigger songs, like Daft Punk’s ‘One More Time.’

“Roxy took the pretention out of clubbing,” Thompson highlights. “At a lot of other clubs on Saturdays, the mainstream night, doormen would look you up and down to see whether you fit the image of their clientele. We offered a venue that was not pretentious in décor or attitude. We did not believe that you had to fit a certain mold; if you believed in having a great time with people no matter what colour or profession, and liked good music and good vibes, there was something for you on a Roxy Saturday.”

That ‘something’ also included the music of fellow Saturday night residents Gadjet, Mike Tull, and Tony Lanz, who played the Parlour and other rooms. Live drummers and percussionists – like iDrum’s Davidson, Vince Vega, and tireless promoter Chico Pacheco – added to the rhythms and vibe.

Mike Tull DJed countless parties on Fridays as well, including Bump N’ Hustle alongside fellow resident Lopes. The release party for Paul E.’s beautiful Whatnaut: House mix CD on Virgin Music was at a Bump N’ Hustle in 2002, with legendary soul singer Gwen McCrae as guest. BNH brought some star power, hosting the likes of United Future Organization, Wunmi and Rich Medina, and Gilles Peterson with Rob Gallagher, aka Earl Zinger.

Hot Stepper also brought the beats to Roxy, from the funky abstracts of Ninja Tune’s DJ Food to partnering with REMG Entertainment on a hip-hop series called Doin’ It. Together, they brought in talents like The Roots’ Questlove, Jay Dee (aka J Dilla), Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest, and Maseo from De La Soul.

Junior Palmer later collaborated with REMG on a few events, including a night in February 2005 with Kenny Dope of Masters At Work on one floor and Questlove on the other.

“One was among the greatest house music producers ever, and the other in one of the greatest hip-hop bands ever,” Palmer emphasizes. “Two different crowds and two different sounds came together for the love of music. It was a great night, and a beautiful thing to see.”

The list of promoters and DJs who came together inside Roxy’s four rooms is longer than I could detail. Toronto’s healthy underground overflowed at the time. Community radio DJs, record shop staffers, independent label owners, and ’net radio talents alike packed Roxy’s DJ booths and dancefloors. Names like Alvaro G, Kevin Jazzy J, Jason Barham, Gene King, Ray Prasad, Dirty Dale, Marc de Breyne, Peace Harvest, Soulshack, Peter Bosco of GarageHouseMusic.com, Hubert K. of Beats.to, and my own appeared on numerous Roxy flyers. Blackmarket Records produced a number of events, including an impressive double bill in 2004 with DJ Gregory and Larry Heard.

“If you were looking for trance and techno, you were at the wrong place,” summarizes prolific producer Nick Holder, who played Roxy a lot considering his tour schedule had him in Europe more often than home.

“Roxy had a very soulful vibe, unlike a lot of other clubs at the time. The atmosphere was not like your typical nightclub; the crowds were mostly regulars who knew what the nights were all about, and the sound was pleasing to the ears. It was also a club that never had any dress code, and no asshole bouncers worked the door.”

Yosh Hsuen led Roxy’s security team. Hsuen was consistently calm, cool and charming while Roxy’s door team was atypically friendly, whether greeting patrons, handling problematic situations, or handing out bottles of water at night’s end.

“The security team really understood what I was trying to create and the importance of making sure everyone had a good time,” Singh credits. “If my staff, especially my doormen, were your stereotypical goons, there’s no way we would have gotten the crowd we did. I let the pros take care of the music, and I took care of the service.”

“From the start, Amar had a vision of a nightclub that was service and hospitality driven,” confirms Scher-McDowall. “He wanted each drink served in seven seconds or less. He wanted the management and staff to form a line at the end of each night to say goodnight. There were so many wonderful staff members, and they all had their own special talents that contributed to the success of Roxy Blu.”

“I have to say that Roxy had the best management, door, and bartending staff that I have ever worked with,” commends Thompson. “There was very little turnover in staff, and I truly believe that was our backbone.”

“The staff was amazing!” Lowcock praises. “Franco was my best bartender, hands down. People would come just to be with him; we built the horseshoe shaped bar for Franco. Kelly Sommerville was perhaps the most energetic, vivacious bartender we had. She always had people dancing at her bar.”

Lowcock also gives props to bartenders including Caterina Salvatori, Karen Zeifman, Jimmy Vlachos, Kate Zenna (“A solid bartender and great actress too!”), and a barback named Colin (“He’s probably a computer genius coder now!”).

“Amar was sometimes tough to deal with,” allows Lowcock; “He’s a perfectionist, but he pushed people to be great, and it worked.

“In its heyday, Roxy was the place to be. We constantly had line-ups, though we were located in a part of Toronto, west of Spadina, that people had said would never catch on. Roxy Blu was a pioneer in the industry.” (Lowcock left in early 2003 to work at the Drake Hotel during its pre-launch and first year. He now lives with his family in Portland, Oregon, where he works as a transportation logistics specialist.)

The area Roxy was located in did, in fact, catch on. Within a few years of its opening, restaurants and bars dotted the neighbourhood. Today it’s teeming with entertainment options, but the environment is notably different than one of Roxy Blu’s trademark traits.

“Roxy fused music and people of different worlds together, and they had a great time,” says Thompson. “In clubland, that is not easy to do at all.

“In my opinion, that kind of magic—where all the right people come together for the right reasons and the stars line up—comes along once in a lifetime. I was truly blessed to be a part of it.” (Thompson later partnered with Junior Palmer to open Toika Lounge, though neither is involved now. Thompson still DJs on occasion, and proudly notes that he has “Two beautiful daughters, both with an ear for music that I strongly encourage.”)

What happened to it: Singh sold Roxy Blu in 2003, partly influenced by feelings post-9/11.

“I thought the world was going to hell in a hand basket,” he says. “Numbers on Saturdays had also dropped, and I was at a point in my life where I wanted to get married and have a child. I was involved in nightclubs for so long that I’d had enough.”

A trio of lawyers purchased Roxy, with promoters including Hot Stepper departing soon after.

“I don’t know the reason Roxy ultimately closed but believe it was because the passion was gone, and other clubs and restaurants in the area became more successful,” says Scher- McDowall, who left at the end of 2003 and went on to manage both Panorama Lounge and Sassafraz. She continues to work in hospitality.

Movement’s Aki Abe was among five partners who opened a nightclub named Una Mas up the street from Roxy Blu in 1999. With a capacity of four hundred, Una Mas focused largely on local DJs who played funk, disco, hip-hop, house, and related grooves. It provided another solid option for Toronto’s underground, as did College Street venue Revival, which opened in 2002.

The Movement crew left Roxy Blu for Supermarket in Kensington Market in early 2005. John Kong remains there for Do Right! Saturdays, named after the Do Right! Music label he founded in 2002. Movement split in 2007, but all members remain active in music. Aki Abe continues to run Cosmos Records; Simon Warwick is a painter who produces Turning Point parties devoted to rare tropical recordings; Jason Palma DJs, continues to host Higher Ground, and is a co-owner of Play de Record; and Nav Sangha is an entrepreneur who opened popular Parkdale nightclub Wrongbar in 2007, was co-owner of The Great Hall, now owns the Turnstyle Solutions company, and more.

Solid Garage, Boogie Inc., and Junior Palmer are among the names active at Roxy Blu until it closed in July 2005.

“Like every venue, Roxy had an expiry date,” says Palmer, who still produces PhatBlackPussyKat events and co-promotes the Do You Love House? series with United Soul. “People get tired of going to the same place every weekend. The area also started to change, and people from Richmond Street started coming to King Street to party. The bottle service craze started to creep into clubs, and things became more about what you wore and drank, and less about the music and sense of community.”

12 Brant briefly became 8 Restolounge and 8 Below. Today, it houses Jacobs & Co. Steakhouse, opened initially by Amar Singh and restaurateur Peter Tsebelis, Singh’s original partner in Bauhaus. Singh remains a minor shareholder in Jacobs & Co., and is now a network marketer, husband, and father to a young daughter.

“Some people started to wish for a comparable alternative space near the end of Roxy, but I always knew that they would look back with longing for a space like that in the future,” comments Carlos Mondesir, who continues to produce Bump N’ Hustle monthly at The Rivoli, as well as parties including Break For LOVE!, the occasional Garage 416 (with Pedro), and Hot Stepper Sundays on Cube’s patio in summer months.

“Nothing has taken Roxy Blu’s place. I think it’s a mistake to ever assume that a club will necessarily work in a different time and place, with different people and expectations. Roxy was right for its time.”

Thank you to participants Aki Abe, Amar Singh, Carlos Mondesir, Denis Scher-McDowall, Junior Palmer, Nav Sangha, Nick Holder, Paul E. Lopes, Pedro Mondesir, Richard Brooks, Shaun Lowcock and Winston Thompson, as well as to Izzy Shqueir, John Kong, Kate Cassidy, Robert Ben, and United Soul.

6 Comments

Hi Denise

Thanks so much for all your Work and love over the Mani years. Every week I usted to 110 min tape your show, and Higher Ground, as well as Cup of Butter. Amazing!!! Thank you!! We still are entranced by Peace Orchestra all these many years later!! Much love, happy listeaning!

Loved reading this article. So many fond memories of Roxy Blu and Una Mas…

also was thinking of Octopus Lounge on Wednesday nights… what an amazing era.

I loved loved loved this article til I read Dale’s comment. “Walked in a dancer left a DJ”… Lmao… And the dancers you shouted out to…. Amazing…. So where were you last night? Oh sorry… You probably had something better to do…

Despite the fact that most of the djs were your “friends” that you stepped on to get where you are…

Or where u think you are anyway….

Sorry everyone…. I’ve kept way to much in for way too long….

The Roxy Blu reunion party was AMAZING!!! JUnior Palmer and Joe Rizla’s sets were the best. I felt like I was back at Roxy…. For real!! THank you thank you thank you!!!

Fond, yet crazy memories of pulling all nighters working on that place. And yes, working on a 10,000 budget was also crazy. I remember finding all the furniture at the Reuse Centre in Burlington and felt like I’d hit the jackpot, buying retro couches for under $50 a piece. Thanks for the blast from the past.

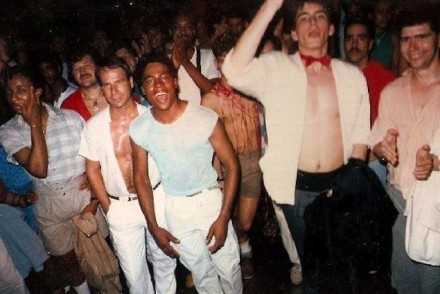

This place was heaven on earth for a dance music lover. Night life never felt so good in Toronto. I walked in as dancer 1998 left as a DJ. Big shout outs to the Dancers. They were huge part of the atmosphere. I layed down some of my most loving and beautiful energy my humanity can produce. It changed me as a dancer. D4c crew, Benzo, Jazzy Jester, Steve, Dwight, Walker. These guys pushed me to another level in that place when it came to dance. One of the most amazing moments was a night Ron Trent was playing. I’m not sure what was in the air? But myself and Tarik from the crew D4C had 9 round dance battle. We must of danced on every piece of furniture including the bar. By the end of it there was no winner. We just looked at each other and said thank you. Moments like that can only be produced in a place of magic that Roxy Blu had.

I completely concur with this Dale. It was a life changing experience for dancer in that Era. Grateful to have witnessed how so many blessed that floor. : )