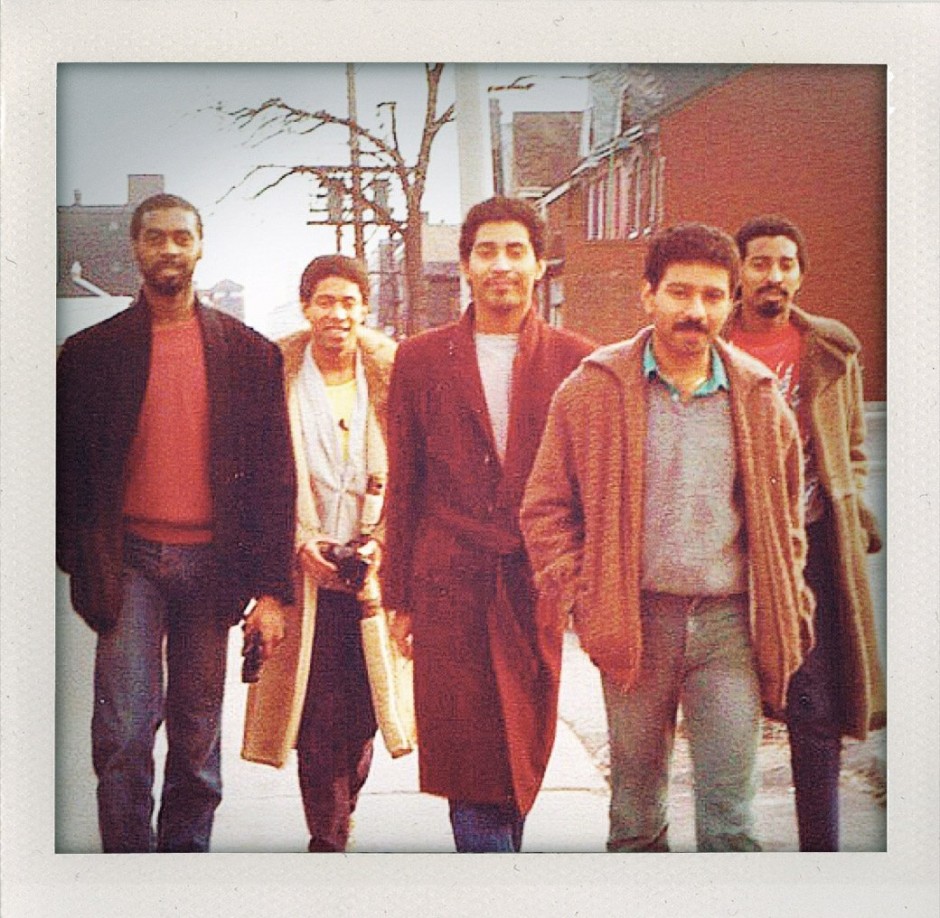

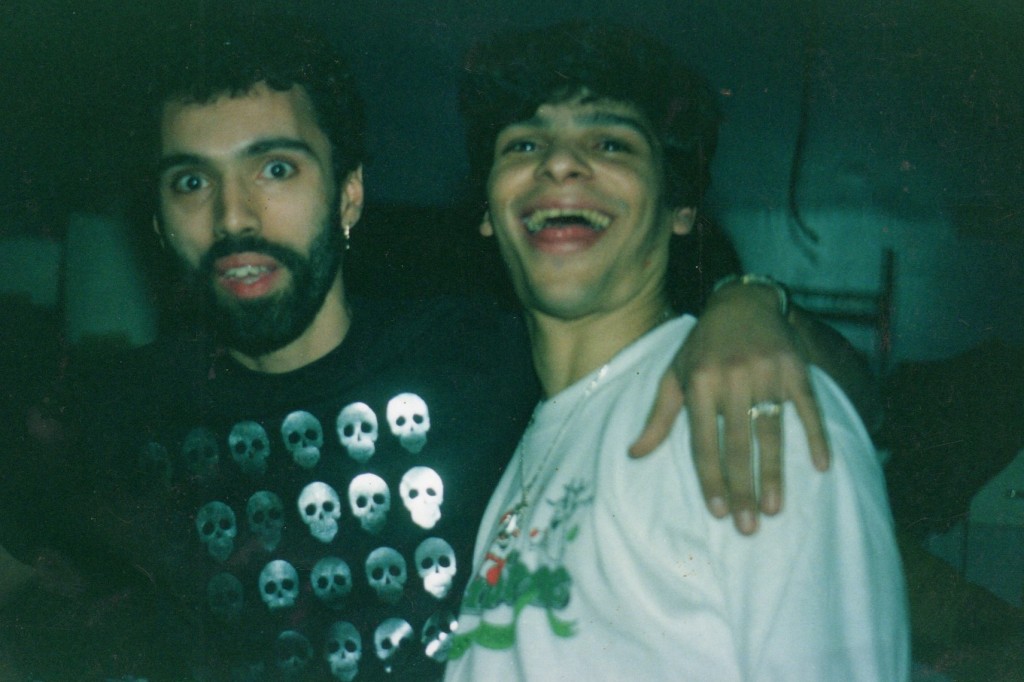

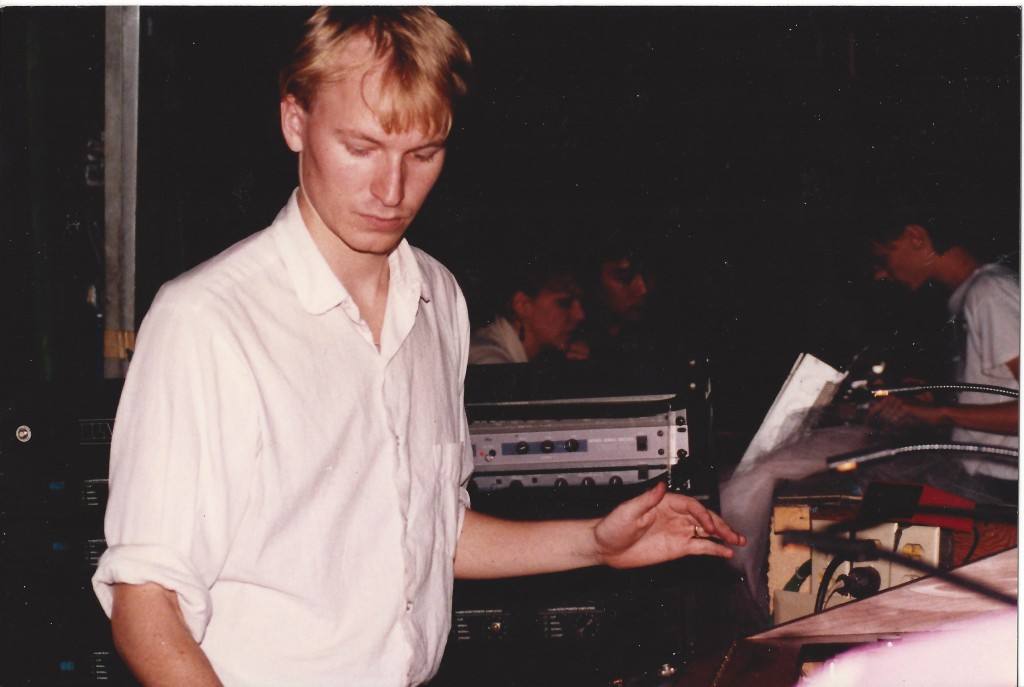

(L to R) Michael Griffiths with Albert, Michael, David and Tony Assoon. Photo by Charmaine Gooden.

The original Then & Now: Twilight Zone article was published October 5, 2011 and was second in the web series originally developed for The GridTO.com. As the Then & Now series expanded in reach, so too did the length of each story and number of participants who contributed to each. This expanded history of the Zone was written in March 2015, and was exclusively available in the Then & Now book until this time.

Trailblazing 1980s nightclub Twilight Zone brought diverse crowds and sounds to Toronto’s Entertainment District long before such a designation even existed. Those who were there lovingly explore its lasting legacy.

By: DENISE BENSON

Club: Twilight Zone, 185 Richmond Street W.

Years in operation: 1980 – 1989

History: Long before the Entertainment District was awash in condos, clubs, and restaurants—back when the area was still largely non-residential and known as the garment district—four brothers opened a venue that ultimately influenced the neighbourhood’s development.

Tony, Albert, David, and Michael Assoon forever altered Toronto’s dance club nightscape with their Twilight Zone, but that venue’s reach was rooted in earlier efforts. The Assoon family moved from New York to Toronto in the 1970s. During their high school years in Scarborough, the music-savvy siblings produced events in school spaces.

“That was back in the day, when Soul Train was on, and we wanted to have something that was more in our culture,” describes Tony Assoon. “We decided to have the first soul party ever in Toronto. It was funk music, a little bit of disco, and so forth. That’s how we started.”

Assoon says they produced a few successful parties, and the idea spread to other high schools before the brothers all graduated. Tony moved back to New York during the height of the disco days.

“I was a club hound,” he laughs during our lengthy conversation. “I went to all kinds of places, like the Commodore Hotel, Night Owl, The Great Gatsby, Paradise Garage, The Loft, and Milky Way.

“One of the clubs that I hung out at a lot, that really influenced me, was called Melons. It was on the top floor of a loft and was a roller skating rink in the daytime. A legendary DJ called Tee Scott played there. Later, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles also played.”

Assoon brought his knowledge and love of New York clubs, style, and music with him when his parents requested that he return to Toronto. He mentions checking our ’70s disco hotspots like Heavens, Checkers, and Mrs. Nights, but landing a job at the Yonge and Bloor Le Chateau clothing store, conveniently located next to a modeling agency, connected him with a different crowd.

“We all loved fashion,” says Tony. “At that time, the whole new wave look was in so we’d dress freaky.”

The Assoons began to do parties at places like The Ports, on Yonge near Summerhill, and in a building on Sherbourne.

“They were great promoters,” says friend Charmaine Gooden of the brothers. She first met them at The Ports, then spent lots of time listening to music with the Assoons and other friends, and attended their early events.

“They started renting rec rooms in apartment buildings to have parties. These were well attended by a diverse, mixed-up crowd—older, younger, money, and fashion. Part of the fun was dressing up. [People came] from Forest Hill, Regent Park, the suburbs, and Scar- borough, so it was varied.”

Through the apartment parties, the Assoons built a solid following and set out to find larger, more secluded spaces.

“We first experimented at 666 King West in September of 1979,” recalls Albert Assoon. “We had to move from there quickly because dust started pouring out of the ceiling from the vibration of the bass. We went on the prowl and eventually wound up at 185 Richmond West. We sought these locations because they were in areas where we wouldn’t get noise complaints or disturb residents.”

“It was desolate,” says Tony of the Richmond and Simcoe area where the Assoons, along with close friends Bromely Vassell and Luis Collaco, launched the Twilight Zone in January of 1980. “It was just industry and factory buildings. Everyone thought we were kind of crazy for moving there, and into a warehouse, but I was used to seeing things like that in New York, so it didn’t seem to be a big deal.”

Soon, crowds would come from far and wide to attend this magical late-night place where the mix of people was as eclectic as the music they were treated to.

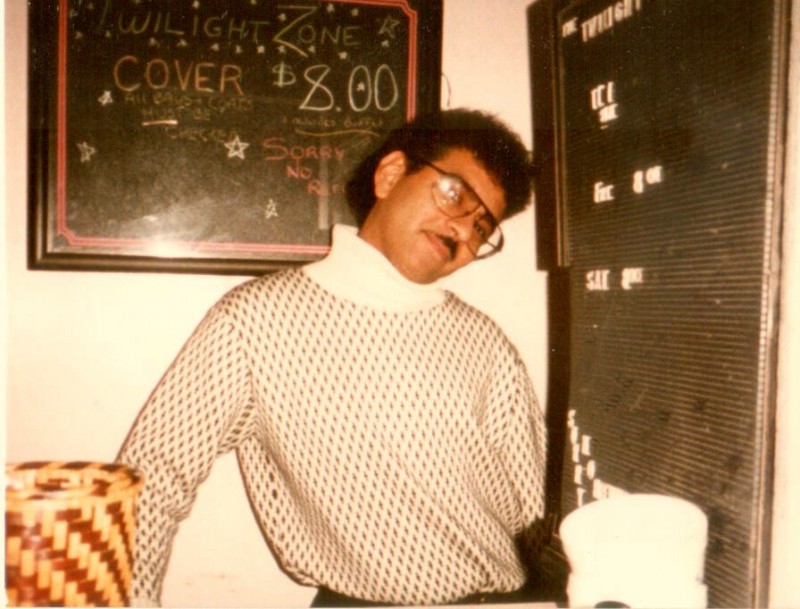

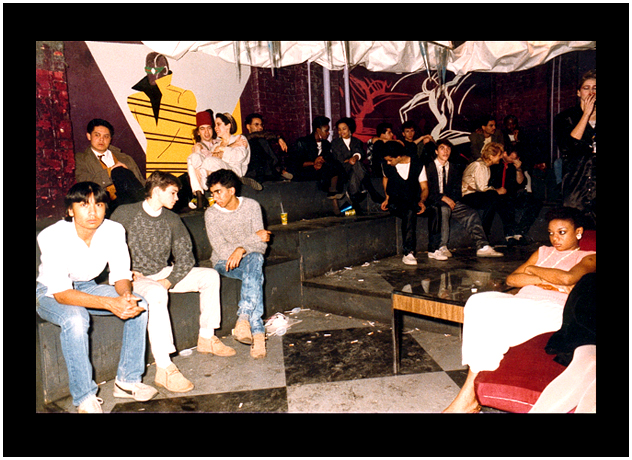

Why it was important: Twilight Zone was an unlicensed after-hours club where the Assoons could let their imaginations run free. The 8,000-square-foot space held more than 1,000 people. It was a rectangular room with a huge wooden dance floor, juice bar, unisex washrooms, and a side lounge for chilling. Tall dark pillars lined the main space.

“You went up three flights of narrow, rickety wooden stairs to the ticket booth and then into a massive room, which was all black,” describes Gooden. “Everything was black. Period. I remember painting a woman morphing into a stiletto on the wall in the lounge area; the whole space was a kind of canvas for creatives. Those guys would let you try out your ideas.”

Twilight Zone was a hub for creative people and colliding influences. Where most other dance clubs tended to be known for a particular sound, the Zone embraced the electrifying collage that was the 1980s. Local and international DJs played disco, funk, punk, electro, hip-hop, new wave, house, and more over the years. There was very little division between sounds that emerged from distinctly different undergrounds.

“You could be playing house and drop in a new wave song; people were right into it,” reminds Tony Assoon. “It almost all started during the same era.”

At Twilight Zone, it could all be heard through a stunning soundsystem. From the club’s start, sound was important. A system rented from Sunshine Sound kicked things off nicely, but it was in the Zone’s second year that a state-of-the-art soundsystem designed by New York’s Richard Long was installed.

“I was used to hearing a certain kind of sound in New York,” explains Tony Assoon of the impetus. “The thing that couldn’t be reproduced was a certain kind of bass. I took my brothers to Paradise Garage, and my brother Michael partied with me a lot at Melons. I told them, ‘Remember that soundsystem? I know the guy and want to put the same system in here.’ They told me to get a price; I think it was about $100,000 U.S. It was a lot of money. At first my brothers said, ‘No, it’s too much,’ but I insisted. We had to close the club for two weeks, and it took a lot of work. We had to spray and insulate the club, and then they got all the speakers and put everything in.

“When we re-opened, it was slow. All the guys looked at me, like, ‘You and your big ideas.’ I said, ‘Give it some time.’ The first group of people came in, heard the system, and didn’t know what to think. The next week, the crowd doubled because everyone started buzzing about the sound. After that, it was all history. People couldn’t believe what they were hearing.”

“When they put in the Richard Long system, the Zone changed forever,” states DJ Dave Campbell, a Zone regular from the time he was a teen. “The bass could regulate your heartbeat, and because the floor was wood, you couldn’t help but dance.

“You could hear the sound from University and Richmond,” Campbell adds. “People would ask, ‘Where is Twilight located?’ I would tell them, ‘Head west of University on Richmond, look for the amber flashing light, and listen.’”

“The sound was like a dream,” agrees Gooden. “Once you’ve listened to music on those amazing speakers, no one can fool you.”

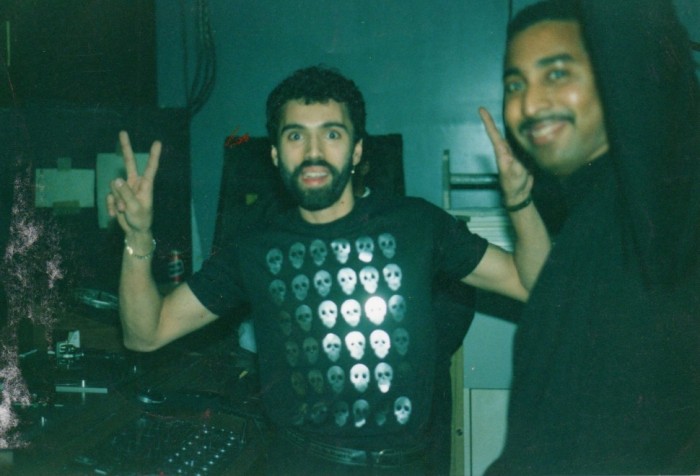

At its core, Twilight Zone was about the music played through that bumping system by its adventurous resident DJs. Weekend nights were divergent yet complementary.

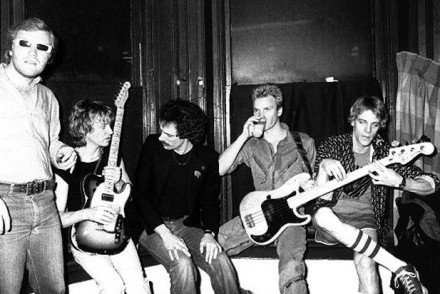

Don Cochrane held down Fridays for most of the Zone’s existence. He first attended the club just weeks after it had opened. Cochrane and a large group of friends “outnumbered the people there” but enjoyed the funky grooves of DJ Albert Assoon. Cochrane and Assoon talked tunes.

“We agreed to meet mid-week for him to hear my UK dance sounds,” says Scottish-born Cochrane. “He and his brothers listened. I got an immediate offer to play the following Friday.”

UK Dance Floor ran Fridays from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. or later, with Cochrane blending new wave and other dancefloor-friendly sounds then-bubbling in the UK with funk, Chicago house, Italo house, German industrial, world beat, and “wild cards.”

Cochrane’s playlist of anthems included the likes of Endgames “First Last for Everything,” Kate Bush “Running Up That Hill,” Bobby Konders “House Rhythms,” Blondie “Rapture,” Bohannan “Let’s Start the Dance,” Jimmy Bo Horne “Spank,” Rocker’s Revenge “Walking on Sunshine,” A Guy Called Gerald “Voodoo Ray,” Liquid Liquid “Cavern,” and “anything James Brown, George Clinton, or Funkadelic.”

He also, of course, featured a hefty dose of UK acts like The Smiths, New Order, Depeche Mode, Talk Talk, Human League, and Bronski Beat, but broke ground when he played them.

“They were ‘retail’ hits, but we had them first—by months, sometimes even a year—as I had them imported,” Cochrane emphasizes. “I did the same for the German industrial dance bands such as Nitzer Ebb. CFNY would come to the booth and monitor my playlist. I got a great kick out of breaking new records—and even sounds.”

“Fridays were the big alternative dance night,” confirms Albert Assoon. “UK Dance Floor featured the new wave you would hear on CFNY, however you heard it first at Twilight Zone. Don was pretty ahead of the music trends abroad and delivered on the dance floor. He would also come party on Saturdays and pick songs he’d then incorporate, giving Fridays more edge than anywhere!

“On Saturdays, the combination of myself and brother Tony was also pretty awesome,” Albert states. “Tony, who had returned to NYC as a teen, came back and would school us all on underground disco. He knew his music and screaming divas very well, and mesmerized the dancefloor with a cappellas on top of stuff. I observed Tony and Don, and came up with my own style, playing mostly funk, freestyle, a bit of new wave, and more.”

Tony mentions a few of his Saturday Zone classics, including D-Train “You’re the One For Me,” First Choice featuring Rochelle Fleming “Let No Man Put Asunder,” and Fonda Rae “Touch Me,” but also makes clear that reggae, early hip-hop, and all sorts of sounds were in the mix.

“We loved playing it all,” Tony emphasizes. “Human League, Thompson Twins, and all the other English groups you could think of were a given. You weren’t a DJ unless you played all of those.”

“I loved it when Albert or Tony would rush up to the booth on Fridays and say, ‘What the fuck is that?’” says Cochrane of the musical interplay. “I would do the same on Saturdays. It was such a mutually beneficial environment that manifested a unique global sound on both nights.

“The Assoons were bold, true to their vision, honest, and pioneers,” he praises. “They were a tight family, and a family who embraced me. Also, [Tony and Albert were] two brilliant DJs.”

Thanks to the Assoons’ vision, the Zone is fondly remembered as Toronto’s first home of garage and house, especially as the music’s bricklayers became imported guests.

“Twilight Zone started off the tradition of bringing international DJs on Saturdays, beginning with DJ Kenny Carpenter, David Morales, Frankie Knuckles, Dave ‘Madness’ Du Valle—all from NYC—and Jay Armstrong from Ministry in the UK,” says Albert. “All the DJs offered a different sound and melted the crowd.”

These connections were largely fostered as Tony Assoon bounced back to New York often to buy music, go to clubs, and hear DJs.

“I was always the type of guy that if I heard a DJ and they sounded good, I’d say, ‘Hey, how would you like to play?’ In those days, DJs were hungry. They would jump to come to Canada.”

Kenny Carpenter was one of the first booked, followed by DJ/producer Johnny Dynell of NYC clubs like Danceteria, The Roxy, and Save the Robots. Dynell suggested the Assoons book a then-up-and-comer named David Morales, which led to repeat visits by the Def Mix master. Morales and Du Valle were frequent guests, sometimes even spinning together, as was Frankie Knuckles. Detroit’s Derrick May and Alton Miller often made the drive to party at the Zone, and both played on occasion.

“Derrick May played a couple of times, but he was a little too advanced,” recalls Tony. “Derrick was playing and making techno long before people knew what techno was.”

Without a doubt, the music heard at Twilight Zone influenced a generation of Toronto house DJs and producers, not to mention a whole host of warehouse party promoters. People like Aki Abe, Dino & Terry, Mitch Winthrop, Yogi Patel, and Nick Holder were regulars.

“Nick lived by the DJ booth,” says Tony of Holder, one of Toronto’s global house ambassadors. “The Zone was a big influence on him because he saw David Morales, Frankie Knuckles, and so on. I think he played a couple of times. Dave Campbell also got put on every now and then.”

Campbell may have DJed at the Zone in the club’s later years, but it took some doing for him and a group of high school friends to pass through its doors. Saturday nights were so busy that staff was selective.

“We were turned away the first few times we attempted to get into the club,” Campbell shares. “We didn’t quite meet the standards of Saturday’s cool, fashion-conscious clientele, so we decided to go on a Friday, as they weren’t as strict at the door. At the time, I was into new wave music and loved CFNY. Some of the music played on Fridays would cross over to Saturdays, like Yazoo, Fad Gadget, Yello, and other tracks, along with the pre-house anthems. We got to know some of the staff, like Bromely at the door, and were finally able to get in on a Saturday.”

Flash-forward a few years, and Campbell had moved downtown, begun to DJ, and was invited to fill in for Tony on occasion.

“The first Saturday night I played, I was very nervous, but it turned out to be one of the most amazing nights of my DJing career. It was surreal playing on that system. It had three turntables, a pitchable cassette player, and a reel-to-reel. When Frankie Knuckles played, he used the reel player to blend in his own special mixes of stuff he produced, like his mix of Chaka Khan’s ‘Ain’t Nobody.’ David Morales used it to play his mix of Whitney Houston’s ‘Love Will Save The Day.’ Dave Du Valle seamlessly worked all three decks at once. He was amazing.

“But what made the Zone so amazing to me, besides the music, was the eclectic mix of people, with white, black, gay, and straight all partying in one space,” says Campbell. “It was like nothing I had experienced before, including the unisex bathroom.”

Twilight Zone was the place to be, with large, diverse, and creative crowds dancing ’til dawn week after week.

Gooden, who attended regularly for most of the club’s nine-year history (“Always from after 2 a.m. ’til close”), encapsulates the experience. “It was the kind of place that was so overwhelming, a kind of free style, with people dancing all over the place. It gave waspy, stuffy, uptight Torontonians a release valve where people could just be bohemian and extravagant.

“The Zone was a mix of black, white, Asian, old, young, hipster, fashion-trendy, new wavers, break dancers, young punks, skinheads, and Scarborough secretaries in their outfits. You had the Scarborough blacks, Charles and Church Street gays, Queen West alternatives, and people from Whitby to Etobicoke. Those years at the Twilight Zone were like a cauldron with all the people who got mashed together.”

“It was a weird era when everyone got along,” comments Tony. “All the people who listened to house music started showing up on the new wave nights, so you’d see somebody in a suit dancing next to somebody with a Mohawk or somebody who was a skinhead. Half of those kids didn’t even know why they were wearing Nazi flags in the back. They’d be dancing with everybody; if they were that prejudiced, they wouldn’t have been there, dancing beside somebody black or somebody Jewish or gay. Everything was more for fashion than it was for a reason.”

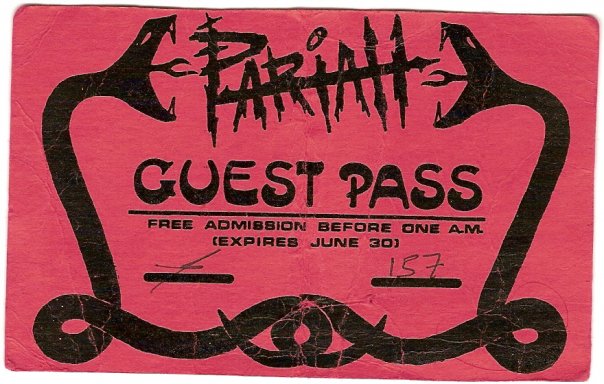

“It was unique and without aggro,” agrees Cochrane; “They came for the music.” This was also true on Pariah Wednesdays, which ran in the early through mid-’80s.

“Wednesdays were more underground,” describes Tony; “Pariah catered to the more punk kind of crowd.”

Pariah had its roots in the downtown arts and music scene. Toronto club veteran Lynn McNeil had launched the night with DJ Siobhan O’Flynn at Club Kongos (later Club Focus) on Hagerman Street. The two met when O’Flynn DJed in The Rivoli’s back room for L Squared, an influential event promoted by The Katherine with DJs Richard Vermeulen and Pam Barnes. (“To my knowledge, Pam was the first woman DJ in Toronto, and I was the second,” says O’Flynn.)

After about a year at Kongos, Pariah moved to Wednesdays at Twilight Zone, with O’Flynn joined by DJ Stephen Scott.

“Coming out of Hagerman, the music at Pariah was a mix of punk, disco, old funk, and the start of the early ’80s Brit scene,” she describes. “We played The Fall, Wire, early Stone Roses, and American punk and post punk, like Television.

“Pariah would have been the first place I played Sisters of Mercy ‘Gimme Shelter.’ I still re- member that song on that soundsystem was damn impressive. It was just so immersive to experience vinyl records played on such a stupendous soundsystem. You just felt it. Being able to listen to PIL, Joy Division, and the big orchestral Sisters of Mercy sound in a room with perfectly EQ’d sound was incredible.”

Hundreds came out between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. each Wednesday. “You had to be pretty committed,” comments O’Flynn; “You weren’t holding down a job that you had to be at at nine in the morning. Pariah started with a very strong foot in the emerging counter-culture punk scene. There was also a whole group of underage alternative school kids. The club scene or bar scene was just starting to take off, so we’d get that after-hours crowd, and Goths.

“Broadly, it was hungry alternative music fans, which is why people were so open to really diverse genres of music. I know that a lot of people came to the club specifically to be introduced to new music. Both Stephen and I were avid consumers of tracking what was new, reading NME [New Musical Express], and buying imports.”

In addition, O’Flynn redecorated Twilight Zone’s interior every few months (“I’d source out non-flammable materials that you could have in environments where people were behaving chaotically”), and booked in local indie bands of the time, like Change of Heart and Groovy Religion.

“There really weren’t that many places you could go out and hear the music we featured,” recalls O’Flynn. “For the Assoons to let us have our night in their club was always kind of amazing.”

Who else played/worked there: “I love that for a lot of high school kids, the Zone was their first memory of a club,” says Tony. “We’d open up early for them, and then close. They’d want to stay, but we had to say, ‘No, you’re not 16.’ We were all-ages, but you had to be 16 to stay after hours.”

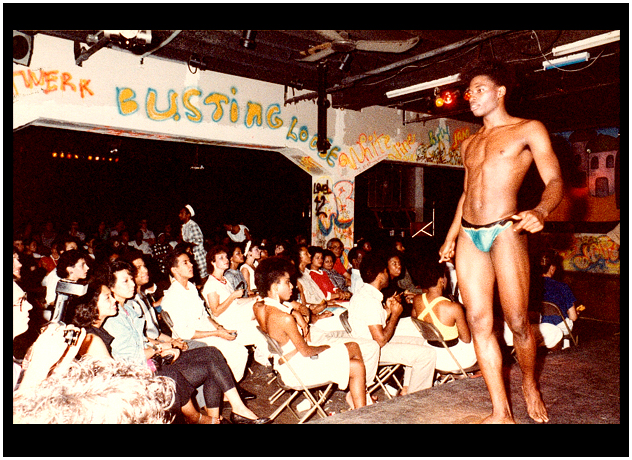

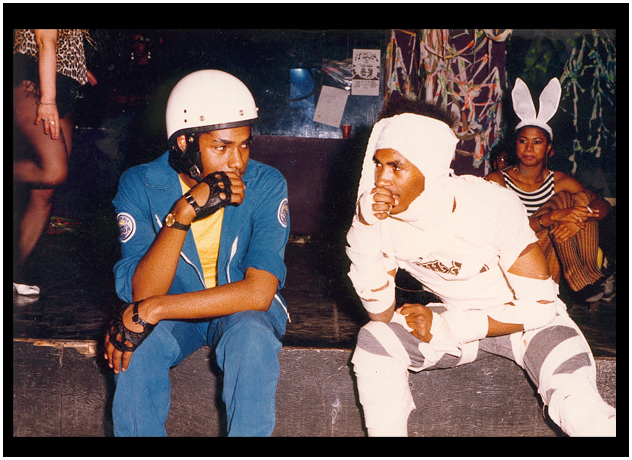

One night that stands out for its early-evening crowds was when the Assoons brought New York’s Dynamic Breakdancers in for a show.

“That was around the time that Herbie Hancock came out with ‘Rockit’,” Tony recollects. “We packed that club from six in the evening until 1 a.m.. They did maybe four shows. People just kept coming; they wanted to see what this breakdancing was all about.”

Further proving the brothers had their fingers on the pulse of multiple musical movements, the Zone also featured performances by artists as diverse as D-Train, Divine, Sharon Redd, Joycelyn Brown, Jermaine Stewart, Prince Charles, Anne Clark, The Spoons, and The System.

“One year, we had an anniversary party without any acts booked,” adds Tony. “I happened to see Eartha Kitt crossing the street and called out, ‘Eartha Kitt?’ She said, ‘That’s me.’ I said, ‘I would love for you to come and sing. We have no act tonight. Tell me what you want, and we’ll work something out.’ Her response was, ‘I want two things: a cold bottle of champagne and a champagne glass.’ She came on stage, sang ‘Where Is My Man,’ and had so much class. Amazing.”

Albert recalls a visit by a certain New York hip-hop trio. “We had the Beastie Boys in. They went on a rampage and graffitied the club. We had just sanded the area and it wasn’t painted, so we decided to leave it as part of the decor.”

O’Flynn also remembers that eve, and laughs as she shares an anecdote. “It was probably 1982 and the Beastie Boys were at the club. They wanted to spin, and I said no. I kicked them out of the DJ booth. To this day, I can’t believe I did that.” (Post Pariah, she went on to play plenty of speaks and clubs, including Domino, Dance Cave, RPM, Nuts & Bolts, the Bovine, Phoenix, and Left Bank. O’Flynn is now a professor and consultant who teaches digital media at the University of Toronto.)

A variety of other DJs spent time in Twilight Zone’s DJ booth over the years.

“The Zone’s music was unique,” summarizes DJ and radio producer Scot Turner, who went by Skot during his eight years as a programmer and host at pioneering alternative radio station CFNY 102.1FM. He went to the Zone often enough to appreciate its musical mix, and to support it with on-air mentions.

“Their reputation was for house music, but also for their openness to alternative, which they were not afraid to embrace and showcase. Anyone with a love of dance music and vibe was welcome.”

Turner, in fact, DJed a Thursday night called Swoon for a short stretch. “The music format was intentionally non-bass and beat, with lots of jangly guitar. It was art rock and pop—The Smiths, Cure, REM, Violent Femmes, Prefab Sprout, Lloyd Cole, and the like.“

Turner also DJed at venues like Club Z, Club Focus, Empire Dancebar, RPM, and Joker over the years, and would go on to help launch Energy 108 (“The first true all-dance music station in North America”). He appreciated Twilight Zone for many reasons.

“It was bare bones, but the soundsystem was first rate. It was what proper club sound should be: very loud, without hurting your ears, and with bass that you feel in your chest. It was not licensed, so the music came first. Without the distractions of alcohol and ‘picking up,’ it attracted a more purist music crowd. (Turner is now Brand Director for two Kitchener radio stations and contributes to The Spirit Of Radio web page at Edge.ca.)

There were also attempts made to have a dedicated gay Sunday, with DJs such as Barry Harris, Paul Grace, and Stages’ resident Greg Howlett. Tony admits it never took off, and the reason he provides is a reminder of the division that existed even in more tolerant and mixed spaces.

“When AIDS happened, that made a huge difference in who would go where. People started thinking in stereotypes, and stuff like, ‘If I touch somebody gay, I’m going to get AIDS.’ People could be very discriminatory. Meanwhile, I was still going to gay bars, trying to book DJs. I went to a gay club—The Roxy—to book Frankie Knuckles. I had so many friends who were gay that I didn’t pay that kind of stuff attention. I really wanted that crowd to be part of my crowd. Nobody enjoys music more than a gay crowd; those were the guys who brought satisfaction to my turntables.”

While the Sundays never came together, there’s no question that communities did on other nights at the Zone. Throughout the club’s history, artists, performers, and the fashion-forward were a part of its core crowd. Actors and hockey players were also in the mix.

“Patrick Cox, the designer, came there a lot,” says Tony. “So did Wayne Gretzky, Mario Van Peebles, and Grandmaster Flash.”

“At The Twilight Zone, you had Kenneth Cole, Suzanne Boyd, Michael Griffiths, the Soho designers, Dean and Dan of Dsquared, and other local artists who were regulars,” adds Albert. “Many greats met up and fully expressed themselves with their look and attitudes!”

The highly fashionable Charmaine Gooden also mentions many fellow regulars. “Donna Boyd was a presence; when she danced, it was like there was a spotlight on her. She held her body, singing, acting, and living out the song. She was just so glamorous and had a smouldering personality. We gave some of our favourite regulars nicknames: There was Richard ‘National Ballet,’ Suzie Horton was ‘Jacket and Panty Hose,’ Tony and Basil Young were like the Nicholas Brothers. Ronald Holmes, who worked the bar, was from New York and a one-man dance squad. People gathered around him to learn his particular style.

“Some people never went to church, but they were at the Zone every Sunday morning,” elucidates Gooden. “For some, it was a spiritual experience. The music on Saturday was also very based in gospel.”

The aforementioned Tony Young, later known as MuchMusic host Master T, was frequently found on the dance floor, as was Michele Geister, who co-founded and produced MuchMusic’s RapCity program. Photographer Michael Chambers was another regular, as was Tom Davis, who later booked the Cameron House and now owns The Stockyards restaurant. Others mentioned by interviewees include Lyndon Hector; Norbert Ricafort; Ford Medina; Marla Rotenberg; makeup artist Danny Morrow; clothing designer Ian Hylton; Raymond Perkins, who ran The Dub Club at the time and went on to work as Director of Culture at Roots; and Aaron Serruya, who produced his first party at Twilight Zone and is now co-owner of both Yogen Früz and Red Nightclub. Darryl Fine, now co-owner of the Bovine, was a regular who sometimes tended bar.

There were a lot of dedicated staffers. Some include original Zone investors Luis Collaco and Bromley Vassell, who went on to do lights and door, respectively. Gerald Ash and Lino Santos were core bussers for years, while Chris Arthur worked the door and more. Dave Campbell also mentions host Ted Aman, and Lisa McCleary, who worked in the Night Gallery, below Twilight Zone.

“We took over space on the ground floor and opened a café called Night Gallery in 1984,” explains Albert. “We offered a free buffet with the $10 admission, and it was generous. I swear some people came just to eat.”

The Assoons’ father was the main Night Gallery chef. Sometimes there was music in that space as well.

“Twilight Zone was my first official club gig,” says Derek Perkins, who took over Fridays after Don Cochrane left to pursue his career at Ogilvy One in 1987 (Cochrane shares that he went on to launch the Air Miles program and now works in the airline industry).

Perkins “started playing alt and classic rock downstairs in the Night Gallery. At that time, there was no alt format on any nights upstairs. Within two to three weeks, the room reached capacity and the Assoons gave me Friday night in the Zone.”

Other DJs who played occasional Fridays included Larry St. Aubin (aka Larry Saint), Ivan Palmer, Michael X, Avery Tanner, and James Stewart, but Perkins was the main resident. Fridays became known as The Darkside. Perkins also came to play on Wednesdays.

“Prior to working there, I was a huge fan of Pariah and of DJ Siobhan,” he credits. “She was a huge influence on the style I later adopted, mixing classic rock and funk with alternative.”

He namedrops personal anthems by the likes of Patti Smith, Aerosmith, Love and Rockets, Felt, and The Demics, but he also “included artists such as Boney M, Blondie, Man Parrish, Grandmaster Flash, George Kranz, and other beat-centric stuff so some of the dance crowd would stay. They mixed in pretty well with the freakier late-nighters.”

Perkins also shares a vivid, sensorial memory.

“There was a smell like no other place I’ve ever encountered. The best I can figure is that it was a mix of French Formula hairspray, cologne, perfume, hashish, coco puffs, coconut fog fluid, stale booze, and bathroom odour. It was an oddly intoxicating smell.”

He was the last alt DJ to play at the Zone and was there until the club’s demise.

“The crowds would go up and down as more competition came to the area, but there were almost always enough people to make it viable,” says Perkins, who went on to play clubs including Nuts & Bolts, Freak Show, Empire, The Copa, Whiskey Saigon, Klub Max, and Zoo Bar. (He then ran creative departments for multiple radio stations, and now markets luxury real estate.)

What happened to it: “Near the end of the Zone’s run, the crowd had become younger,” says Dave Campbell. “It seemed that the sanctuary had changed. There was no more Celestial Choir ‘Stand On The Word’ or Lonnie Liston Smith ‘Expansions’ played as the Sunday morning sunlight came through the window. We had lost our church.” (Campbell went on to play a range of clubs, including The Copa, The Diamond, and Roxy Blu. He now runs his own DJing service, is the Friday resident at The Citizen on King West, and plays parties including What It Is! and Twilight Zone reunions.)

The Zone’s crowds may have shifted in its final years, but they still filled the club. The venue closed in early 1989 because the Assoons’ lease had expired and the building’s owner sold the property. It became a parking lot.

“We would have bought the building,” says Albert; “However, despite our successes, the banks would never finance us with anything—except the one time my father put up his house for us to buy Twilight Zone’s soundsystem. We had to sign a waiver where our unborn children would have to pay if we defaulted. That loan was paid on time and in full, but they would not agree with our vision.”

Twilight Zone came to a close soon after a February party that featured David Morales. People still speak of the club—and the communities it brought together—with deep appreciation.

“The Zone was like a club in the real sense; everybody felt they were part of the club,” says Gooden. “When you saw an ex-Zoner elsewhere, you had a connection. To this day, Zoners are still a sub culture.” (She is now a magazine editor and Professor in the School of Fashion at both Ryerson University and Seneca College.)

The Assoons—also the visionaries who, in 1984, thought to open Fresh Restaurant and Nightclub at 132 Queens Quay E., which was ousted a year later to make way for RPM (The Guvernment later held the address)—went on to open Gotham City Bar and Grill at 81 Bloor St. E. in 1990. Rent was too high for them to make a long term go of it.

Albert and Michael Assoon went on to be deeply involved in late ’90s house haven The Living Room, while Tony moved back to NYC, where he continues to enjoy clubs and music, and works for New York Life. Albert, Michael, and David Assoon now own versatile event space Remix Lounge at 1305 Dundas West.

After more than 20 years of existence as a parking lot, the ground where Twilight Zone once stood has been swallowed into the 199 Richmond West address of the Studio on Richmond condo build. Filmmaker Colm Hogan is at work on Back 2 The Zone, a detailed documentary about the club and its widespread influence.

Thank you to participants: Albert Assoon, Charmaine E. Gooden, Dave Campbell, Derek Perkins, Don Cochrane, Scot Turner, Siobhan O’Flynn, and Tony Assoon, as well as to Colm Hogan, Darryl Fine, and Theodora Kali.

4 Comments

Zoner for life. I have the privilege to work there and go as a patron. Loved the music and atmosphere no matter the music or night involved. From Wednesday night to Saturday night. I grew with zone. As my music portfolio grew so did zone. From English Beat, New Wave to House. I miss the togetherness and friendships. We loved one another no matter race and background. It was all about zone. The fashion and having an outlet in order to express ourselves will never be forgotten. I love all who had a part in blessing us with this special place and time in our lives. We were young but not stupid and knew what we liked. The memories helped mold us into who we are today and I am thankful. Much love and appreciation to all who created it and went and lived it. Zone.

The only band I ever recall playing at Pariah was Shadowy Men On A Shadowy Planet in Feb (?) 1985.

Members of Groovy Religion and Change Of Heart certainly attended the club, but Ms. O’Flynn must be referring to a birthday party at The Bathurst Street Theatre in May or June of 1985, where Change of Heart opened for Sturm Group, Neon Rome, and Tulpa – presented by “Pariah” with Siobhan DJ’ing into the wee hours following the bands.

Great reading these articles, I’ve still got my coat check ticket from the Twilight Zone after a great night and wanting a tangible memory . Wow 30 years later…..!

The youtube video clip was produced, by me as part of a MuchMusic Soul in the City feature on House. Camera by Basil Young.