Stilife interior. Photo courtesy of INK Entertainment.

Article originally published January 28, 2013 by The Grid online (thegridto.com).

After cutting his teeth in nightlife as owner of Club Z on St. Joseph, Charles Khabouth relocated to open this dramatically designed destination spot that kick-started the development of Toronto’s Entertainment District.

BY: DENISE BENSON

Club: Stilife, 217 Richmond W.

Years in operation: 1987–1995

History: Built in the 1920s, the six-storey brick building on the southwest corner of Richmond and Duncan Streets exemplifies the major changes experienced by this Toronto neighbourhood as it morphed from Garment to Entertainment District.

The once heavily industrial area, located south of Queen and bordered by University to the east and Spadina to the west, was occupied by factories, warehouses and daytime workers for the better part of the 20th century. By the 1970s, most of the factories had closed, and many of the buildings lay empty. It was only after the opening of the SkyDome (now known as the Rogers Centre) in 1989 that municipal politicians began to amend zoning laws in order to encourage development in the region.

But in the 1980s, before these sweeping changes took place, the former Garment District was a land of opportunity.

“The neighbourhood at that time was mostly peopled with artists living in affordable studio spaces and cheap apartments,” recalls celebrated installation artist Kenny Baird, who lived in the area and also shared a studio space at the corner of Richmond and Bathurst with his sister and collaborator Rebecca Baird.

“It was pleasantly abandoned, interesting, and ours for a time.”

Boozecans and warehouse parties brought people by on weekends, but otherwise the area was largely deserted at night. The only true nightclub around was the Assoon brothers’ pioneering Twilight Zone, which operated without a liquor license from 1980 to 1989 in a raw space at 185 Richmond West. Parking was even free on surrounding streets.

This was not the most likely part of town for Charles Khabouth to begin his evolution into Toronto’s most powerful nightlife impresario. The founder of INK Entertainment had chosen to open his first venue, Club Z, on St. Joseph at Yonge in 1984 because the area’s “bohemian feel” had appealed to him. In little time, Khabouth had confidence in his ability to anticipate trends, hire the right people, and attract audiences.

“I wanted Stilife to be in a secluded area, where it would be a destination spot to those who came,” explains Khabouth of the club he would open in October of 1987.

His renovation of 217 Richmond West’s 5,000-square-foot basement into a trendsetting lounge and dance club not only created a destination spot, it helped spark the transformation of the entire neighbourhood. Stilife’s influence is felt to this day.

Why it was important: Beneath its understated exterior, Stilife was a club that delighted and amazed patrons who made their way through the main entrance on Duncan. As would become his hallmark, Khabouth went all-out to create a distinctive, dramatic space. He hired local design team Yabu Pushelberg, who brought Stilife immediate international attention with their innovative, award-winning work throughout the club.

“I have always had an affinity and passion for design, and Stilife was a great canvas to unleash that,” Khabouth tells me by e-mail. “I enlisted the expertise of now renowned agency, Yabu Pushelberg. Back then, they were very new and unknown, but I saw something fresh in their abilities. They were a massive part of the success of Stilife. Our design collaboration helped communicate an exceptional atmosphere that has people talking years later.”

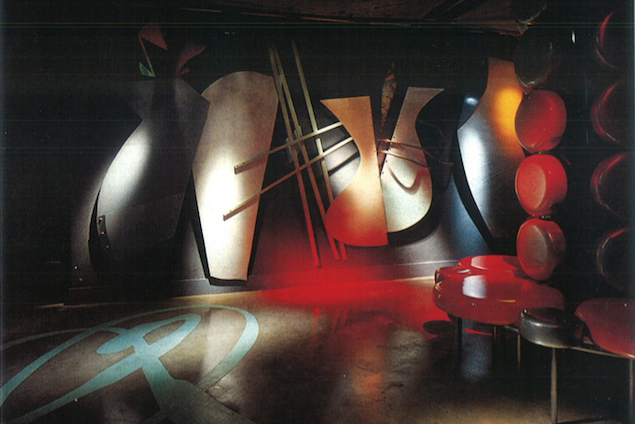

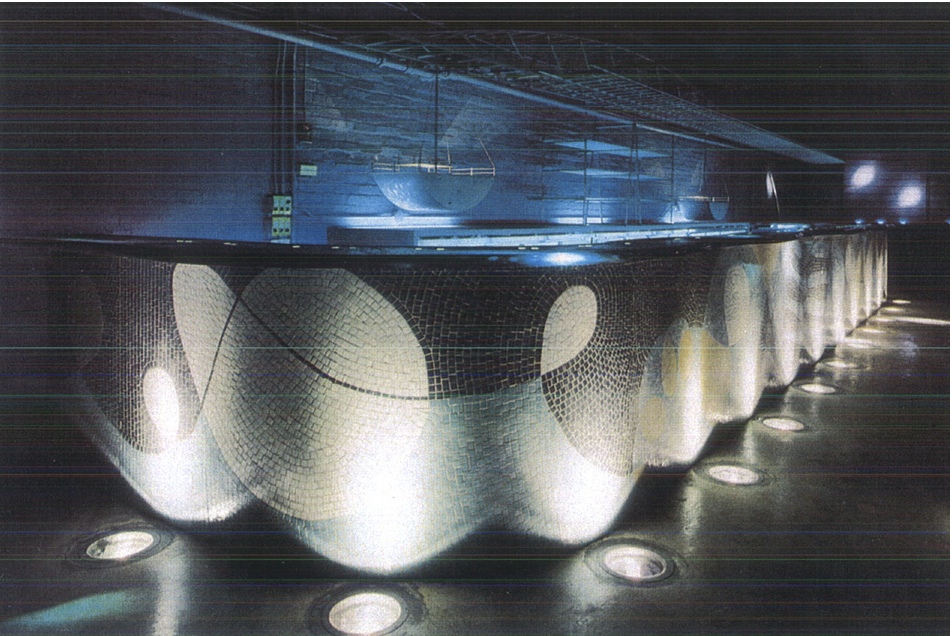

Khabouth is a notoriously hands-on owner who follows the minutiae of his projects through from concept to completion. He undoubtedly had much to do with Stilife’s dark, sculptured aesthetic, which featured a heavy use of polished steel, concrete and mosaic tile. The club’s core elements referenced Art Deco, Salvador Dali and Blade Runner alike. Customers were both on display and could play voyeur.

“It was a beautifully designed club,” enthuses Baird, who had himself completed design and installation work for legendary New York nightclub Area, and would later create some of CiRCA’s most stunning pieces.

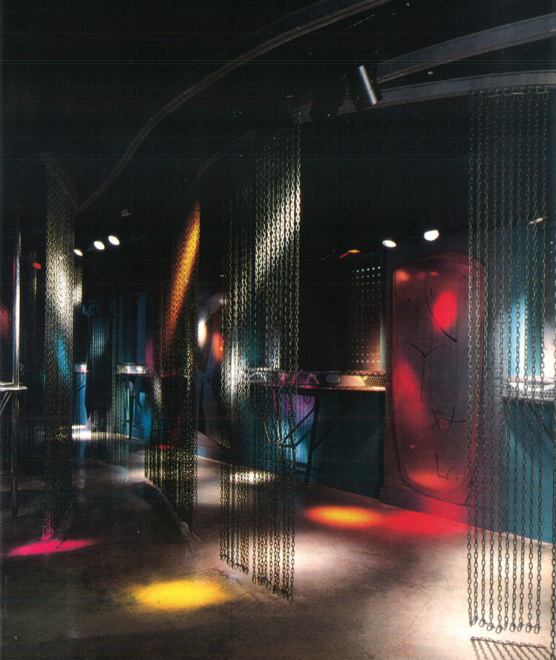

“At that time, no one [in Toronto] was taking these kind of risks with design on that scale. Stepping through Stilife’s burled metal custom entrance doors, down a small, curved flight of stairs, then through a serpentine set of chain-link curtains, one immediately knew this was a space unlike any other. This was one-of-a-kind, custom work—top to bottom, inside and out. You knew that someone had spent time, love and a lot of money to pull this off. It was a design that pulled you into the place with a sense of intimacy and mystery.

“The colour palette consisted of deep subtle hues at a time when bright neon and new wave was the outgoing aesthetic,” adds Baird, who also worked as art director of music videos for the likes of Bowie, Blue Rodeo and Marilyn Manson. “A smallish space by comparison to most clubs, it had a clever design of feeling larger than it actually was. Every surface was an introduction to a texture of luxury combined with carefully chosen industrial elements. It was, in no small words, a jewel.”

“Visually, I can’t remember a more arresting club,” agrees James Vandervoort, a former Cameron House barback and waiter at Kensington Market’s Café La Gaffe, who worked coat check and as a Stilife bus boy in the club’s first year. “The space was so unique.”

“Kenny Baird created these amazing art pieces that you could view from the street. I remember them so well, especially the spiky pair of go-go boots, and a turntable made out of industrial found parts, like saw blades. No one was making that kind of effort for a dance club.”

“I was not one to turn down an opportunity to pay the rent, and Charles was willing to let me do what I wanted,” says Baird of his first creations for Khabouth. “I was asked to install a series of window displays that surrounded the corner of the club at sidewalk level, along with a few display cases inside.

“The pieces were meant to be temporary, and tongue in cheek. [Things like] a demon jack-in-the box eating currency, and a pair of sequined, reptilian platform boots in a box of nails, which was a small nod to the bygone days when one dressed to kill, and practically got killed for doing it. There was a lime green monkey in a box of marshmallows that was subsequently stolen from the display; a murder of black crows pecking at sticks of dynamite, and a golden egg in a nest of thorns. Some of these displays remained sealed, sun-bleached in those windows for years after the club had closed.”

There was humour, function, and detailed craftsmanship to be enjoyed in every corner of Stilife, from the floor-to-ceiling chain mail curtains that separated seating areas from the dancefloor to the custom metal fixtures in the washrooms, and tile work in the showpiece, backlit main bar.

“Stilife’s aesthetic was very forward and edgy,” summarizes Khabouth. “It was raw, but well thought out. Stilife catered to an audience that appreciated fashion, architecture and sophisticated design with a bite—an audience that favoured exceptional music and unparalleled service and experience.”

At a time when most bars and clubs catered to a set core crowd and rarely veered from their course, Stilife programmed a wide range of sounds and themed nights. Its DJs were trendsetters from a variety of scenes and communities. Some were more established than others, but all were very good at what they did.

Two DJs especially made their mark at Stilife: Richard Vermeulen and JC Sunshine.

Vermeulen became synonymous with Stilife’s Tuesday nights. Early on, he DJed while then-girlfriend ‘The Katherine’ promoted, and Kenny Baird designed invites.

“We attracted some of the former crowd from club Voodoo, along with artist friends who fought out a home at the Cameron House,” says Baird of the neighbourhood crowd they reached out to. “We loved to dance to Motown, Stax and Volt, and classic disco. We mixed things up, including Hank Williams, a love for twang, and early rap.

“For some of us, Stilfe was the end of an era in our neighbourhood, and the beginning of what it has become now. But for a short period of time, Charles allowed us to enjoy the place in spite of our night not making any kind of profit for him. He knew who we were and had respect for us, as we did for him.”

Vermeulen, who was not available to participate in this article, remained the Tuesday resident for much of Stilife’s existence, eventually attracting large, diverse crowds. James Vandervoort, later known as DJ James St. Bass, frequently worked the lights to Vermeulen’s music, and remains a fan.

“Richard had such a cool way of mixing genres. He introduced me to Baby Ford’s “Oochy Coochy,” and my acid house craze took root. He would play Ted Nugent’s “Stranglehold,” Bomb The Bass’ “Beat Dis,” and lots of James Brown, disco, funk and good hard rock tunes. Eric B and Rakim’s “Paid In Full” was big too. Richard had this amazing taste in his programming that I admire to this day. He played what he felt like, and had a unique sound that was only at Stilife on the Tuesday.”

Friday night resident JC Sunshine was a master of mixing underground with overground.

He’d come up playing house parties and all-ages events, DJing as part of the influential Sunshine Sound Crew, and had DJed at Khabouth’s Club Z for years.

JC would travel with Khabouth to Montreal to check out clubs (“Charles got some of his inspiration for Stilife from a Montreal club called Business.”), and was brought into Stilife from its inception. He’d mix house with New Wave, R&B, funk and disco, citing Lisa Stansfield, Brand New Heavies, Depeche Mode, Yello, New Order, Fast Eddie, Frankie Knuckles, and Snap’s “The Power” as favourites of the time.

Like many, Sunshine raves about Stilife’s quality set-up.

“The DJ booth was humungous, and the sound was an EV System, which was amazing,” he says. “Charles was always particular with the sound systems in his venues.”

“Since Twilight Zone had closed, Stilife had the best sound system in the city by far,” agrees revered DJ Mark Oliver. He began his decades-long career of working for Khabouth at 217 Richmond in 1990.

“The DJ booth at Stilife wasn’t accessible or even clearly visible from the dancefloor, but the sound was amazing and the lights were state-of-the art too,” says Oliver. “The DJ booth was extremely well maintained, as was the entire club. Considering I was used to playing mainly warehouse parties with makeshift booths, Stilife was a real joy to DJ at. While most club owners would blow their budget on design and the sound system would be an afterthought, in the 25 years I’ve known him, Charles has always provided the complete club package.”

Oliver had come to Stilife after three years of DJing at Toronto venues that ranged from Johnny K-owned venues 4th and 5th and Tazmanian Ballroom to afterhours spots. It was Oliver’s residency at legendary warehouse party Kola that led to his spinning funk, disco and house for gay men at Stilife on Mondays.

“As well as current house tracks, I played all the vogueing anthems, with “Love is the Message” by MFSB, “Is it All Over My Face” by Loose Joints and “Keep the Fire Burning” by Gwen McCrae being the biggest hits.”

“The dancefloor on Monday nights was like one big runway, with drag queens competing for the spotlight,” Oliver describes. “While Madonna was on her Blond Ambition tour, she came to Stilife with her voguers who took over the club that night. The energy was through the roof. The regulars, funnily enough, were more excited about the voguers being there than Madge herself.”

Stilife soon gained a reputation as a celebrity hangout.

“Notable guests, such as Madonna, George Michael, and Prince, fuelled its success,” asserts Khabouth. “Stilife truly was one of the first venues to attract the who’s-who, and this gave the brand a cachet that couldn’t be found anywhere else.”

Stilife, in fact, had an exclusivity factor that was central to its image. Even as he courted cool, the image-conscious Khabouth was incredibly selective about who would make it through the doors of his intimate club.

“The door policy was very exclusive,” says Oliver. “Many say Stilife was the first to have such a policy, but Johnny K’s Krush started that whole trend in Toronto. The difference between Krush—followed by Tazmanian Ballroom—and Stilife was, in simple terms, style versus money. Johnny K’s policy was based solely on style. The doormen at Krush and the Ballroom would tell guys pulling up to the door in Lamborghinis to go home, and try showing up in a cab next time to have better luck. They would then proceed to open the ropes and welcome a freak wearing pajamas. Stilife was the opposite.”

“With a capacity of 400, we were limited in how many guests we could let in,” explains Khabouth. “Our policy at the door was to maintain an audience of like-minded guests—guests who were mature, sophisticated, and liked to socialize in a certain environment.”

This ‘certain environment’ tended to be populated by attractive, well-heeled patrons who did not live in the neighbourhood. Stilife was largely a playground for the rich and glamorous.

“The clientele was mostly of a very high-income status,” says JC Sunshine. “There were many major league athletes, fashion and entertainment industry people. If you didn’t fit in any of the above categories, you would be at the mercy of the door staff. Many of them were either actors or models themselves—really tall, well-built and good-looking—and they had tough standards, based on Charles’ specifications. It was very hard to get in.”

“Stilife wasn’t for everybody,” confirms Jim Kambourakis, a Toronto club industry veteran who installed sound and lighting in dozens of top venues around the city, Stilife included.

Also known as Jimmy Lightning, for his lighting skills, Kambourakis worked as Khabouth’s right-hand-man on Richmond from 1989 to 1994. He speaks of Stilife’s most iconic doorman, Robin.

“Robin was so tall. He stood above everybody. He had this crazy long hair, and always wore these big jackets. Anyone who wanted to come in had to go through him.

“Charles used to hang out at the door, smoke a cigarette, and he would sort of wink or nod to tell Robin whether to open the door or not. It was a controlled environment, based on attitude, age, and fashion.”

Still, even with all the designer duds and celebs in attendance, Stilife’s DJs maintained their musical integrity.

“I remember one night when Wayne Gretzky came to the booth,” recalls Sunshine. “He requested a slow song for him to dance with his wife to. This was at about 1 a.m., and the club was packed, so needless to say I didn’t do it—not even for The Great One. Charles would have flipped if I had changed the formula of the night. Charles wouldn’t veer from his vision; that’s why he’s the king of clubs!”

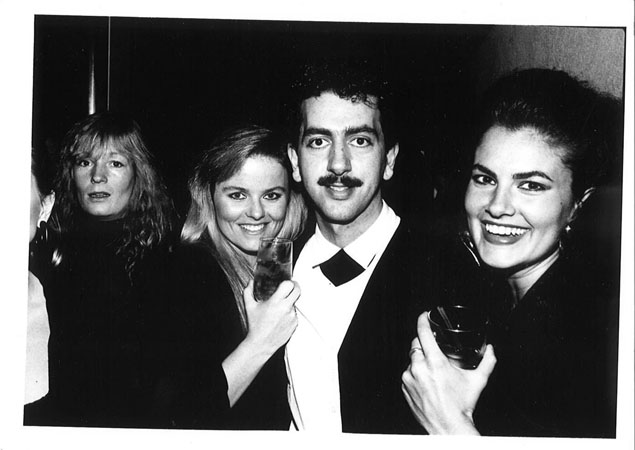

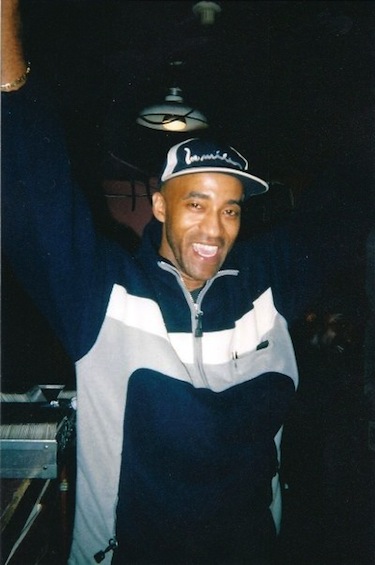

Stilife owner Charles Khabouth with a few of the club’s patrons. Photo courtesy of INK Entertainment.

Who else played/worked there: Even a partial roster of Stilife DJs reads like a who’s-who of top T.O. spinners and producers. Barry Harris was a resident at the club in its first year, until he got too busy with his Kon Kan project. Local legends like Terry Kelly, Vania, Dino & Terry and Matt C held down residencies, as did duo Bill & Amar. DJ Chris Klaodatos was a popular Saturday night spinner who went on to play at other Khabouth-owned clubs (“I hear he’s in Greece and has become a monk,” Kambourakis says.).

Thursday nights at Stilife were both devoted to house music, and more alternative electronic sounds over the years. Even DJ Iain McPherson and promoter James Kekanovich—known for alt nights at clubs like The Copa, Empire Dancebar and, later, Limelight—were given a go.

“It was a pretty hard electronic alternative night,” says McPherson of their series of events that also included on-site tattooing, body piercing and the like. “I was impressed that they went for the idea of having us play there; it was so open-minded for the time. Alternative music nights were generally held in dark, inexpensively built clubs. Stilife had been beautifully designed, and was run with great professionalism.”

Stilife managers included Vincent Donohoe, an investor in Club Z and later the co-owner of clubs including Turbo.

Stilife’s staff certainly added to the club’s allure.

“There were many bar staff who enhanced the whole Stilife experience,” credits Sunshine. “So many of them were really gorgeous women and very studly looking men. There was a bartender named Gautier who was very charismatic, and had a special appeal to all the patrons, both male and female.”

A large percentage of Stilife’s staff—DJs, managers, and bartenders alike—would become familiar faces in downtown Toronto clubs over the decades.

Sunshine, who stopped working at Stilife in 1994, went on to DJ at clubs including Fluid, The Guvernment, Joker and The Phoenix, where he held down the long-running Planet Vibe Sundays. He continues to DJ to this day.

Richard Vermeulen would go on to loom large in DJ booths at clubs like Boom Boom Room and The Rivoli.

Vandervoort became James St. Bass when he too began DJing at the Boom. He went on to play at multiple T.O. clubs—including Go-Go and Limelight, which both opened not far from where Stilife once stood—as well as at raves, warehouse parties, and on the air at CIUT with his influential Sunday Hardrive show. He continues to DJ, including as a resident at vinyl-centric monthly party Black Crack Funk Attack.

Mark Oliver’s DJ career exploded soon after he’d started at Stilife. By 1991, he had become one of the main faces behind Toronto’s then burgeoning rave scene, playing at gritty spaces like 23 Hop, which opened at 318 Richmond in 1990. Oliver left Stilife to DJ five nights weekly at the Ballinger brothers’ club Go-Go, which had launched at 250 Richmond West and brought a whole new wave of clubbers to the district.

“By drawing clubbers to Richmond Street, Stilife broke the ice for future clubs in the area,” says Oliver, who’s now best known as the longtime Saturday resident at Khabouth’s Guvernment Nightclub. “I reckon Go-Go, and the cluster of clubs that followed in the district, would never have flourished without Stilife paving their way.”

“I’m sure many will agree that Charles took Toronto club design to a new level,” says McPherson of Khabouth and Stilife’s shared impact.

“I think he raised expectations amongst clubgoers in a way that was felt for many years afterwards—perhaps continuing until today. No longer was it acceptable to just paint a room black or do some cheesy disco-era treatment. The design of Stilife was world-class, and taunted every club that followed to step up its game. Just about everyone who went, or worked in clubs, felt the impact over time.”

What happened to it: By the early 1990s, a number of other nightclubs had opened along Richmond and Adelaide West, and Charles Khabouth’s attentions were divided. He’d already opened a series of upscale restaurants—including the short-lived Oceans, which had adjoined Stilife and starred chef Greg Coulliard, Boa Café, and Acrobat—but hadn’t yet gotten his recipe right. In 1992, Khabouth opened Yorkville nightclub Skorpio and later invested in the area’s famed Bellair Café. He sold Stilife in 1995.

“After eight years, I had grown out of the space and was limited with what I could do, in terms of ceiling height and capacity. It was just time to move onward and upwards.”

That he did, opening The Guvernment in 1996, and expanding it over time into a huge, ambitious entertainment complex boasting multiple rooms and concert venues. Since then, Khabouth has well outgrown his ‘king of clubs’ tag, opening restaurants and venues, and investing in property developments, all at a dizzying rate.

In 2012 alone, Khabouth launched restos Patria and Weslodge, converted his Ultra Supper Club into CUBE, redesigned many rooms at The Guvernment, bought the old Devil’s Martini and turned it into UNIUN, and purchased a controlling stake in Sound Academy. Additionally, the INK magnate partnered with Lifetime Developments to develop the boutique Bisha Hotel & Residences project, slated to open by early 2016 at 56 Blue Jays Way, where Klub Max once stood.

Now 50, and with his company reportedly valued at more than $50 million, Khabouth shows no signs of slowing down.

“We are geared up to continue our growth in 2013,” he writes. “We are pleased to be opening up a second location of our French bistro, La Societe, with the Lowes Hotel Group In Montreal. We have also partnered with the Sound Academy, and will be programming some big talent events. As well, have partnered with the Buonanotte Group of Montreal to bring the Italian supper club to our former space, Ame, on Mercer Street. (This building, at 19 Mercer, was once part of OZ, The Nightclub.)

“Looking to expand south of the border, INK is currently working on signing a deal in Miami too. The sky is the limit, and we are excited to be a part of Toronto’s growing social culture.”

Not yet mentioned is the fact that Khabouth and Jim Kambourakis are business partners in both Niagara Falls superclub Dragonfly, and the recently closed This Is London (Kambourakis left Stilife in 1994 to open Orchid and, later, Tonic. He heads The Lightning Group.)

“Something new is coming,” says Kambourakis of the now-being-renovated former site of This Is London, at 364 Richmond West. “It’s time.”

Baird, who worked extensively on UNIUN Nightclub, and continues to contribute to INK-owned clubs, respects Khabouth’s leadership.

“Charles was, and still is, taking the risks required to deliver original, award-winning design to this city. Stilife was a prime example of his vision and talent.”

Following the closure of Stilife, 217 Richmond West opened as Fluid in 1995. It later became the short-lived Pop Nightclub, and then lay vacant for a period as the neighbourhood continued its evolution. Increasingly surrounded by condo projects—including a few exciting OCAD-related developments—the space will no longer beckon dancers. It will soon open as The Fifth Pubhouse & Café.

Thank-you to participants Charles Khabouth, Iain McPherson, James Vandervoort, JC Sunshine, Jim Kambourakis, Kenny Baird, and Mark Oliver. Thanks also to Barry Harris, James Kekanovich, Melissa Leshem of INK, and Tyrone Bowers of Allied Properties.

3 Comments

good for you, Lisa! Robin was nice at first but his ego got out of control…

I grew to intensely dislike everyone associated with that club. (except for dear Kenny) they treated me and ‘my people’ – those who came out on my tuesday nights – sooo badly. even though those nights were MY brainchild… but I was just a woman.

I about fell off my stool when I saw my name actually mentioned in this article! although I was relegated to mere “promoter” status. ‘producer’ is more correct. plus I made the invitations! amazing, and amazingly busy Kenny Baird did me the honour of designing the opening night invite, but I did the rest. (his was beautiful, mine just did their job.)

let me also add that Charles ‘found’ Kenny through me.

further re this article, Charles is b.s.ing through the whole thing. the Stilife I saw was always pretty empty – except on my tuesdays – which, btw were called ‘Ocean’. I guess that little detail was left out because after we left, in 1988, Charles took the name and used it for the restaurant… with an added ‘s’, mind.

my night was named in honour of the

Led Zeppelin song, ‘Ocean’, which perennially uncool Charles would never have known.

anyhow, Lisa if it was ‘Ocean’ that you were turned away from, please accept my apologies.

no matter which night you were there, that ‘rich looking folks only’ policy makes me sick. I just learned about it now. in 2024.

but something tells me it didn’t apply on my nights… ha!

congratulations on your successes!!! please remember the experience you mentioned here and don’t ever be like THEM..!!!

I could never get into that club on my own. It seemed to me that you had to be a pothead or cokehead to get in. I didn’t do drug, so any time I ever did get in, it was with a friend who did do drugs. It was quite a trade off and wasn’t worth the drama.

I do remember Robin and he’d look right through me. Lol. By the end of its time, I remember walking past him in his fur coat and nobody was in line. That’s what happens when you treat people like they are invisible.

Now, I’m a film producer and invited to all sorts of parties, but I still don’t do drugs, so maybe Robin wouldn’t let me in even today.

All comments in the string below have been republished from their original appearance on The Grid website. We’re including the readers’ comments as they add to these Then & Now stories. We look forward to reading new comments here as well.

Marty

Much respect to the dJs of the past.

I tip my headphones to you all.

http://mcfly.ca 5:48 pm on January 28, 2013