Poster wall of memories. Photo by Lucy Van Nie.

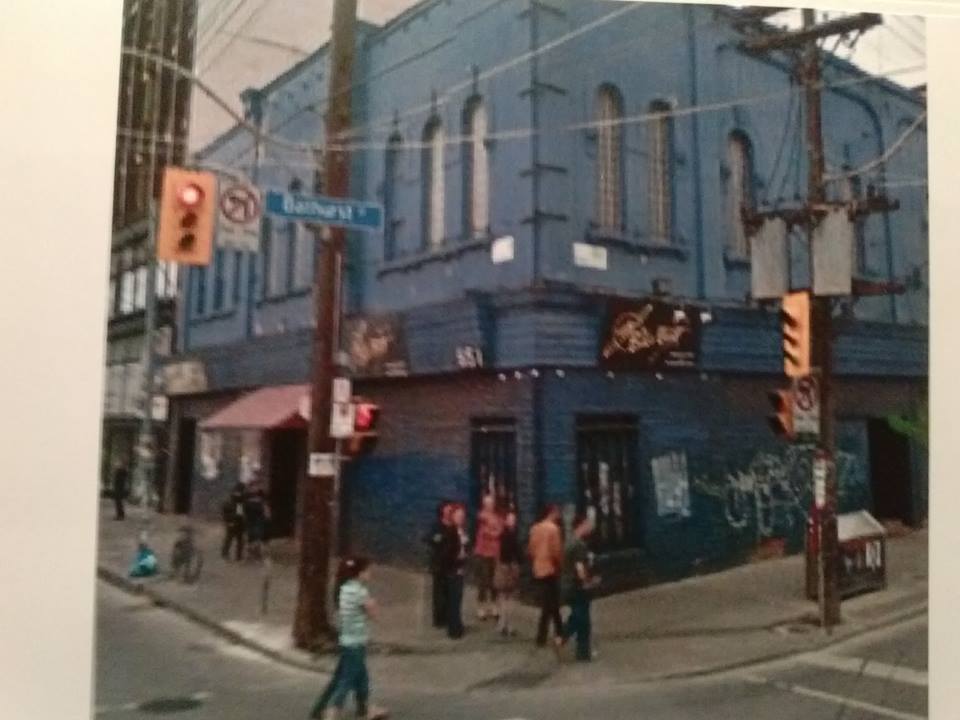

In the second half of the 1990s, the iconic purple building on the southeast corner of Queen and Bathurst underwent a transformation from dance club to all-ages live music hub. What now houses a modern furniture and décor store was once home to punk, metal, hip-hop, Darkrave, and a whole bunch of proud music misfits.

By: DENISE BENSON

Club: The Big Bop, 651 Queen W.

Years in operation: 1997 – 2010

History: Often, we must look back in order to move forward. That’s certainly the case with this story. When last we delved into the history of The Big Bop, it was during its period as a dance club owned by the Ballinger brothers.

Interviewees for that story were hazy, at best, about the closing of the Ballinger’s Bop. It was clear that the venue had suffered financial hardships from 1994, when it went into receivership, but concrete details about its eventual end – let alone its evolution as a club space – were scant.

As it turns out, the original Big Bop continued to operate until 1996 under the management of Peter Ballinger.

“Peter was the least seen and the least involved until the Ballingers bought Webster Hall, and the other three brothers – Lonnie, Steve and Doug – were in New York,” recalls Trevor Mais who, as DJ Tex, rocked crowds in the building through three different club incarnations.

Mais was an employee at the original Big Bop from 1989, working as busboy, bar back, lighting tech and, from 1993, DJ. While he also did lights at Go-Go and played at clubs including Boom Boom Room, The Phoenix, Joker, and Beat Junkie as DJ Tex, Mais had especially deep ties to Big Bop. He tells me that the club truly struggled from 1995. Various attempts at revival failed.

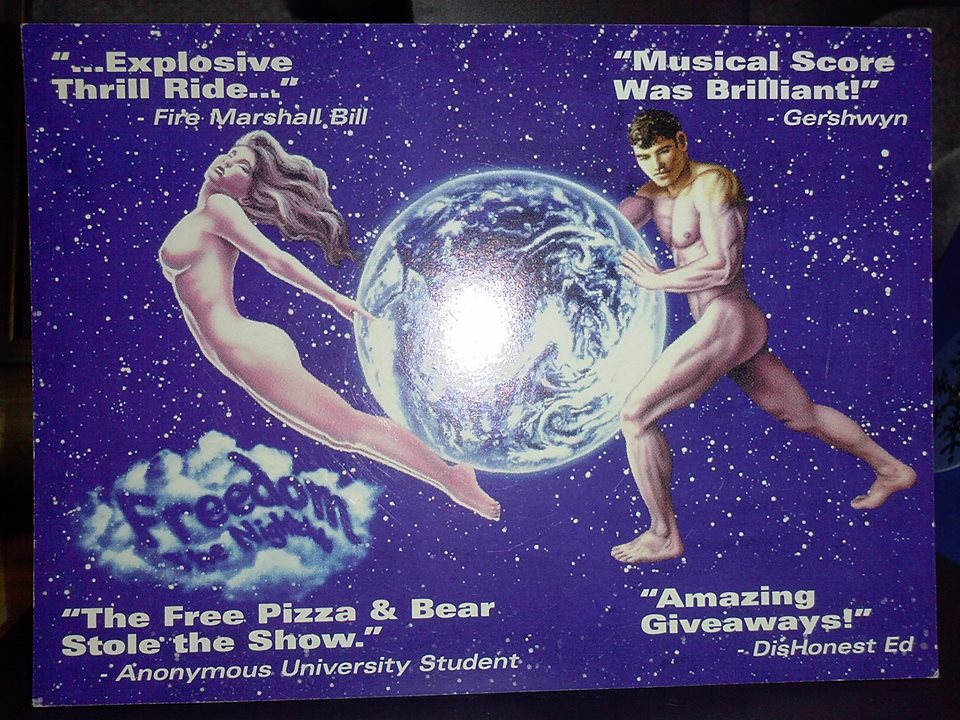

In spring of 1996, the building at 651 Queen West opened as Freedom: The Nightclub.

“The transition to Freedom was helmed by Jim Tsiliras, who [told me his] father Nick had owned the building since it was the Holiday Tavern, and that the Ballingers leased it from them,“ says Mais, who played rock, retro, R&B and disco on Freedom’s ground floor Wednesdays through Fridays.

“The Big Bop’s main floor [street level] only closed for one week during the transition to Freedom,” he recalls. “I never stopped working; the main floor was always a viable source of income. That’s why they didn’t overhaul it. The second floor, however, got a million dollar overhaul, and was closed for at least six months.”

Mark Micallef, a Toronto club veteran who DJed at venues including The Copa, Klub Max, and original Big Bop, concurs with the timeline and details offered by Mais.

Micallef was a resident DJ on Freedom’s second floor for the club’s first few months, but says that even with “completely new sound and lighting” and a clubbier approach to the music played, the venue “never really took off.”

Micallef moved on to play at Joker, located at 318 Richmond West. Freedom came to a close a short while later.

In 1997, the building was suddenly re-branded as The Big Bop by new owner Dominic Chiaromonte, the man who would come to paint it purple and guide the venue, however inadvertently, in a very different direction.

Previously, Chiaromonte had owned Ukrainian Caravan restaurant, with locations in Etobicoke and Yorkville. He tells me that after a decade of operation, Ukrainian Caravan went under. Next, he had three silent partners (including cousin Dominic Tassielli) who wanted to invest in a nightclub with him.

They looked at a number of downtown locations over the course of almost a year, until the Bop building came up. It was in the hands of banks at that time.

“I knew of the Bop because I used to be a patron, especially on Depression Wednesdays,” says Chiaromonte during a lengthy phone conversation. “The Big Bop was the nightclub for a thousand people in Toronto back in the mid ‘80s to early ‘90s.

“I knew the building, and liked it. We jumped on it. It was easy to jump on because the banks wanted to get rid of it. We worked out a very good price for that time.”

“When Dom took over in 1997, the building never closed either, and he switched names right away, without hoopla or fanfare,” recalls Mais.

Without missing a beat, DJ Tex went on to spin classic rock and alternative on the new Big Bop’s main floor.

“In the new Bop era, we moved the DJ booth right to street level, and opened the corner windows so you could look right into the belly of the beast. Some staunch Bop purists didn’t like the change, but change was happening all around – musically, and in terms of owners, staff, times, fads and looks.”

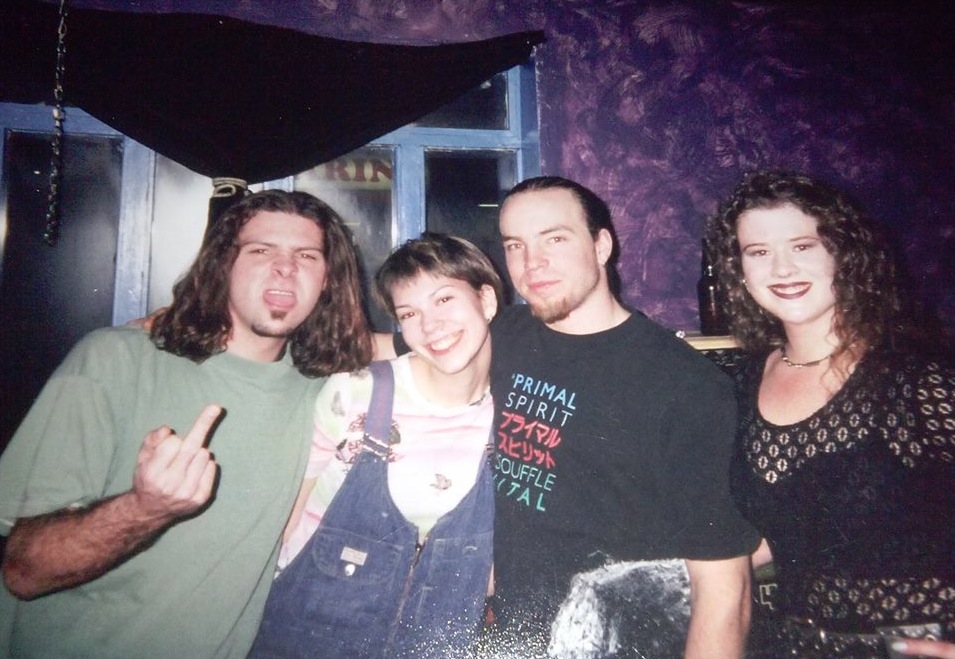

L-to-R: Steff, Karen, Trevor ‘DJ Tex’ Mais, Sherry in the Bop’s main level, 1998. Photo courtesy of Mais.

The conversion: While the capacity of the club – roughly 1,000 people, between all floors – never changed, the Big Bop’s main function sure did. Chiaromonte hadn’t planned a shift from dance club to live music venue, but that’s what happened.

“To tell you the truth, we didn’t know what we were doing,” he admits. “We just wanted to get into the club with the DJs, and at that time that seemed more logical, in terms of the salaries. We realized within months that it wasn’t going to work out. We just couldn’t compete with the big dance clubs at the time, like Joker, Whiskey Saigon and Limelight, where people were flocking. That area had become the core for DJed nightclubs by then. We realized ‘This is why the Big Bop went under.’”

A musician friend, Yurko Mychaluk of Seven Year Itch, suggested that Chiaromonte and partners book bands. Inspired by the support of live music at venues like the Horseshoe, Lee’s Palace and El Mocambo, he agreed.

Mychaluk also suggested Chiaromonte hire talent buyer Yvonne Matsell, who had booked blues acts at Albert’s Hall, been central to the success of outstanding Queen West roots and indie rock venue Ultrasound, and also worked at the Horseshoe.

Though The Big Bop was not known in live music circles at the time, Matsell agreed to check out the spot.

“When I saw the middle room, I felt that the venue had great potential,” she recalls. “I thought that if I could bring my following, the room would be a great space for bands to play.

“The upstairs room was really lovely and I thought it was prime for singer-songwriters. It was very intimate, and the thing that sold me on it was all of the fairy lights in the ceiling. They also had a piano, which wasn’t any good, but lent itself.”

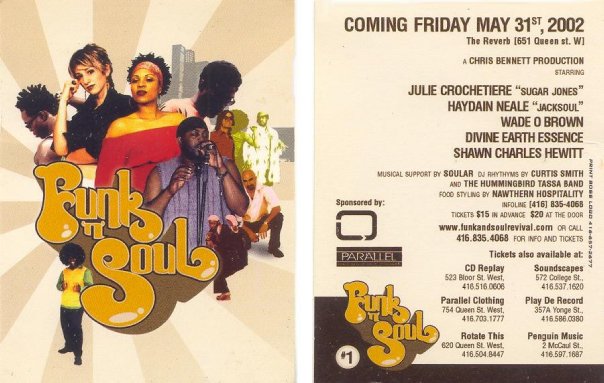

Matsell agreed to book those rooms, which she named Reverb and Holy Joe’s. The venue’s identity as a dance club was put to rest as sound, staging and lights were brought in.

As a good-sized room with a large stage and great sightlines, Reverb became a new home for record label showcases, touring acts, and more established Toronto bands. Matsell’s early bookings, which set the tone, included Dave Alvin of the Blasters, Austin’s Alejandro Escovedo, Michael Franti’s Spearhead, and the first Toronto appearance of Third Eye Blind.

“The Rheostatics played a packed gig the night that Princess Diana died [August 31, 1997],” recalls Matsell. “I vividly remember her tragic accident being played out on the bank of TV screens over the Reverb bar, while the Rheostatics played, unaware of what was happening and why the audience had their backs to them.”

Holy Joe’s became known a cozy spot to catch talented singer-songwriters and largely solo artists.

“I began residencies up there with people who, at that time were really new to the music scene in Toronto, like Jason Collett, Hawksley Workman, Danny Michel, Emm Gryner, and Amy Millan, before she was in Stars.”

“Yvonne kick-started us, there’s no doubt about it,” credits Chiaromonte. “She was the one who gave us credibility, and basically put us on the map. She knew who to talk to, and all kinds of bands started to come and play.”

Despite her efforts and connections, Matsell was let go after about two years (“They decided that they were paying me too much money, and thought they could do it themselves.”). She immediately went on to book seminal College Street music hub, Ted’s Wrecking Yard.

By this point, the Big Bop featured live music in all three rooms. Chiaromonte had to fill them.

“There was a period of time that I was booking, likely for about six months,” he recalls. “I tried to go the same route as Yvonne, musically, but I couldn’t get the bands that she got, and I couldn’t compete against the Horseshoe because they had all of these loyal bands and agents who didn’t want to play for me. It was very discouraging and really rough, but what came into the picture was a lot of young bands.

“I remember talking to my lawyer and asking ‘What’s the rule for having all-ages events at a nightclub?’ He told me we could do it. He also told me that the chances of getting busted when you do all-ages are a lot greater, but I had no choice. And what I realized was ‘Hey, I could charge rent for all-ages shows.’ Because we wouldn’t make money from alcohol sales, the promoter would have to pay us rent to compensate. For some reason, bang – It boomed! We became known as the all-ages club.”

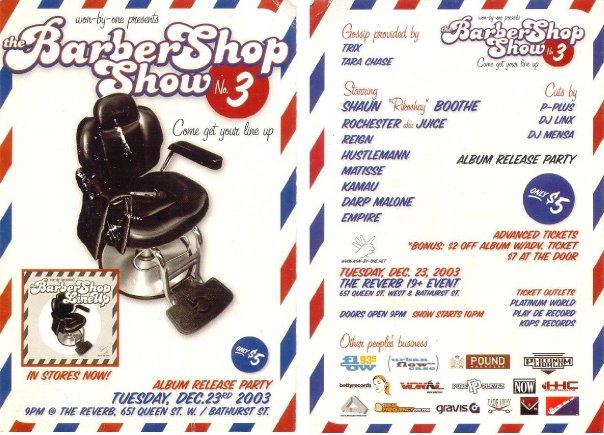

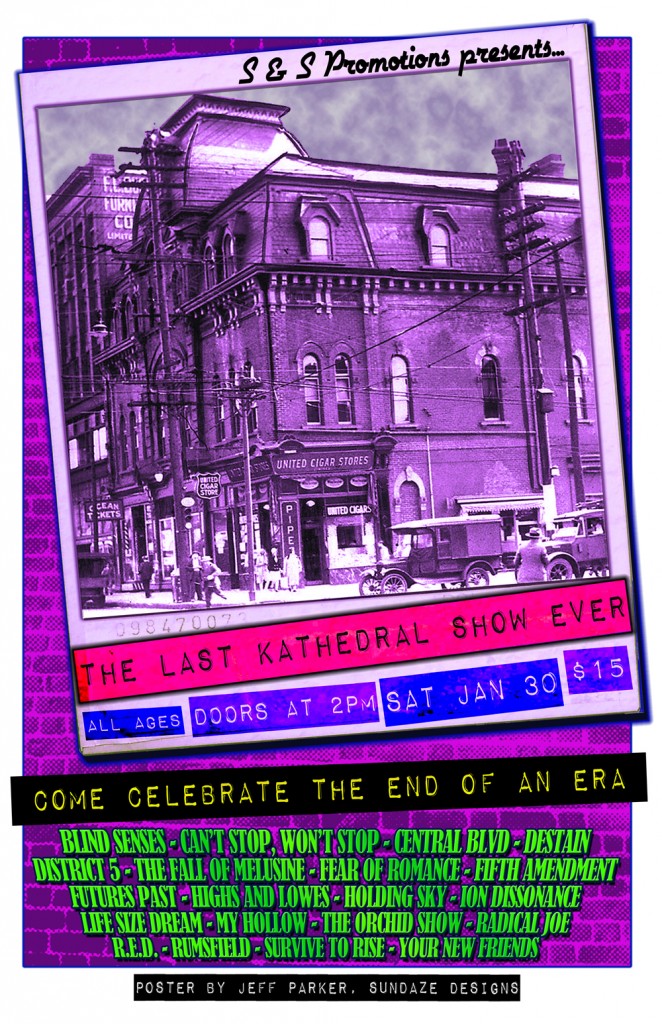

The transformation was made all the more complete when Chiaromonte hired Noel Peters to book the Bop’s street level space in mid-1999. Peters, who had founded Inertia Entertainment in ‘96, primarily promoted metal and punk shows, featuring both touring and local acts. He gave the ground floor its name.

“As the Reverb had an identity as did Holy Joe’s, my thought was to view the entire complex as ‘The Big Bop’ and give the ground floor its own Identity,” Peters explains. “Metal and punk music can basically be a religious experience so I came up with ‘Kathedral.’”

Reverb, Holy Joe’s and Kathedral would retain their names –and feature wildly varied sounds- for the rest of the Big Bop’s run.

Why it was important:“The Big Bop complex was a classic product of old Queen West culture – free wheeling, open to all, value priced, hard drinking and disdainful of intolerance of any type,” states concert promoter Ewan Exall. “That was reflected in the booking policy, which at some point brought just about anything you could imagine to one of the three stages.”

Exall, who’d grown up downtown and landed his first job next door to the Bop, at army surplus and outdoor store King Sol, was happy to book shows at the corner of Queen and Bathurst. He brought in dozens of touring punk, hardcore, metal and indie bands – initially working as part of Against the Grain Concerts, then on his own – between 1998 and 2010.

“I really loved the Big Bop, and it was a central part of my life for 10 years.”

It was easy to love the Bop building as a music fan. All three rooms were a great fit for their function. Reverb had particularly good sound, a wide layout, and was an ideal showcase space for music of any genre. Holy Joe’s, with its couches, felt like a living room where you might just discover your next favourite artist. Kathedral was dark, gritty and perfectly suited to aggressive rock.

Chiaromonte’s need to fill all three rooms multiple nights weekly resulted in an unrestricted booking policy.

“We opened the Bop to anything and everything. We opened it up to whoever wanted to book it. It didn’t have to be a metal club. It didn’t have to be a punk club. Or a rock club. Whatever came around, that’s what was slated for that day.”

Talent bookers / promoters Andrea Caldwell and Noel Peters at the club in 2002. Photo courtesy of Peters.

It helped that Chiaromonte had some solid in-house bookers who could make sense of it all. Soon after Peters was hired to focus largely on Kathedral, Andrea Caldwell was brought on board to help book Reverb and Holy Joe’s.

Though she didn’t then have much experience, Caldwell was immersed in different music scenes, from acoustic to funk, hip-hop, and indie rock. She had worked at Sneaky Dee’s and Gasworks, organized singer-songwriter nights at The Artful Dodger, and got hired at the Bop after producing a multi-venue benefit series for The Red Door Women’s Shelter.

“The show at Reverb went really well, and Dom needed a booking agent,” Caldwell recalls. “By the end of the night, he offered me a job. I woke up the next morning and started calling all the musicians I knew.

“Dominic’s main concern as a club owner was to book events that would bring crowds into the venue; he didn’t favour any particular scene or make his choices based on musical opinions,” adds Caldwell. “That gave us the freedom to take chances, and support several different music scenes at the same time. As well, it was the only club around that supported the all-ages scene, which attracted many talented kids who just needed a chance to get up on a stage and work things out.”

While not all shows held at the Bop were all-ages, most were. Noel Peters agrees that this was both rare and much needed.

“The Bop was really the only small all-ages-friendly venue in the city, and for live music, it was great to have the opportunity for a younger generation to come and see their favourite bands or to discover upcoming ones. Within a year or so, demand was high for the space, and we had the Bop running as an almost seven-days-a-week operation.”

This gave rise to a new generation of musicians – and promoters – who were able to develop within the purple and black walls.

“I think the Bop was most important for being the place that gave almost every band a chance to play their first gig ever,” says Jake Disman, an audio technician who had previously done sound at the Cabana Room, and started at the Bop in 1998 as a fill-in for house tech Aaron Michielsen.

“Bands that had no background, and no real fan base, who could never have gotten a chance to play the Horseshoe, played the Bop,” Disman adds. “Kids grew up [seeing bands] there, and when they started their own bands, that’s where they aspired to play.”

Bands like Alexisonfire, Down With Webster and Billy Talent, while still known as Pezz, played some of their earliest shows on Big Bop stages.

“Down With Webster’s Tyler Armes and his friend were on the streetcar one day and they had heard that the Big Bop did all-ages,” recalls Chiaromonte, “They were young and couldn’t book themselves any place so they came to talk to me. I set them up with a gig, and over the course of 10 years, they did between 10 to 20 shows at Big Bop. Now they’re huge.

“Same thing with Alexisonfire; they played our club quite a bit, and then when they got big, they did a special show at the Bop, which was very cool of them.”

Down With Webster, in fact, recorded live sets at Reverb to compile a six-track debut EP titled The Reverb Session July ’03. They sold this CDR at gigs.

“There were a lot of firsts for artists and promoters in that club,” says Caldwell; “First live show, first weekend gig, first time playing a new song live, and so on. The Big Bop gave you space to try out ideas.

“Also, the great thing about having three floors is that we could accommodate musicians and bands at all different stages of their development. I was given the opportunity to book residencies and on-going showcases with artists such as Down With Webster, Cleavage, Pilate, Lindy Ortega, Justin Nozuka, Wave, Graph Nobel, Samba Squad, Die Mannequin, and many more. It was always wonderful when the crowds grew from 10 people to hundreds.”

The development of bands on Bop stages contributed, in turn, to the growth of this city’s live music scene. More bands, more fans, more people out supporting live music would be the simple equation. There was also no shortage of music industry people who spent a great deal of time in that building, scouting and showcasing talent.

“We saw up-and-coming bands perfect their sets and grow their careers right before our eyes,” describes sound tech Lucy Van Nie, who launched his audio career at Holy Joe’s in 2000.

“I remember mixing Tegan and Sara there to a crowd of about 65 in the early 2000s,” says Van Nie, later the house tech of Reverb. “I remember mixing Hedley for a label showcase a few months before they blew up and took over pop rock in Canada. Bands like My Darkest Days, Alexisonfire, Die Mannequin, and Canadian rockabilly royalty The Creepshow used the Reverb as a home base to try out material and tighten up stage shows before first big singles and national tours.”

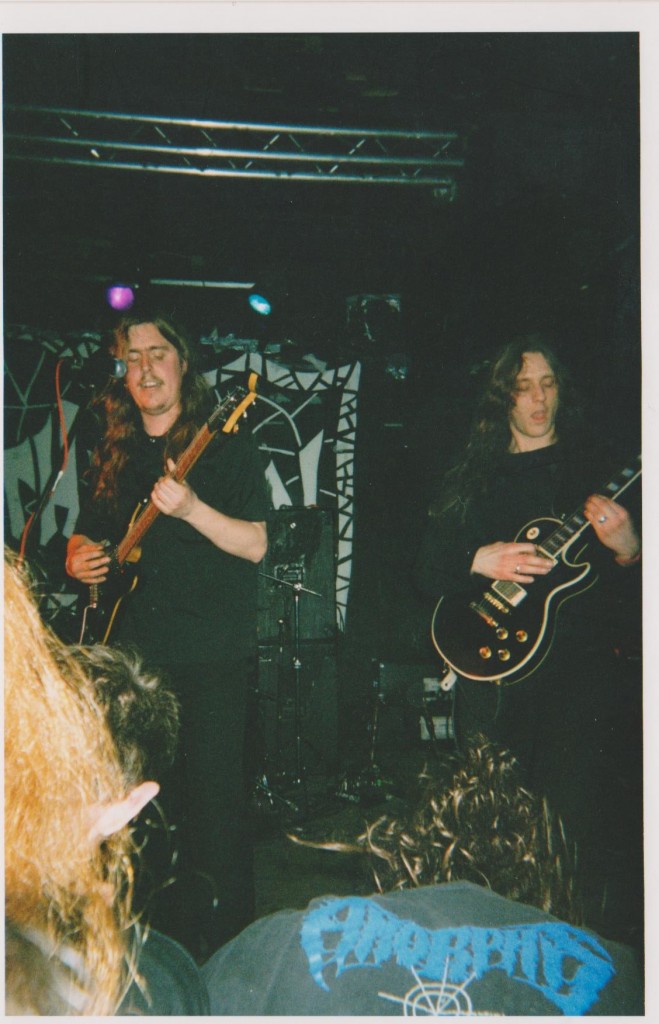

And then there were the outsiders. The Big Bop – Kathedral in particular – was known as the place to catch punk, metal and hardcore bands, both touring and local.

“Kathedral was a dive to say the least, so that’s where almost all of the punk and metal shows were,” describes longtime Bop staffer Scoot DeVille. “You can’t really destroy a place that’s already been destroyed. There were so many holes in the walls.”

Hundreds of local punk acts played the various Bop stages over the years, many of them booked by John Tard of The 3tards.

“John brought in just a staggering amount of punk bands, mostly Canadian,” credits Jake Disman. “He was a very big part of the all-ages successes that we had.”

Exall also recalls that “Over the nine or so years I did shows there, a who’s who of indie, punk, emo, metal, and hardcore touring acts came through the door.”

His top memories include performances by Cro-Mags as well as fellow American punks AFI (“Those shows were always total mayhem, kids swinging from the pipes, the whole bit.”) as well as a certain dubstep star in the making.

“An incredibly young Sonny Moore – 15, I think – fronted his screamo metal band From First to Last at the Kathedral in 2004. They were second out of three bands on some touring package. I always knew that kid would be a star. We at Embrace still work with him as Skrillex, which is one of the things I am proudest of in this stage of my career.

“But the consensus seems to be that the best show I ever did there was At the Drive-In opening for Get Up Kids,” Exall adds. “No one really knew who ATDI were at that point; the Vaya 10-inch had just been released. All standard rock superlatives apply to their performance that night.”

Exall also speaks of booking local punk band No Warning multiple times, including on bills with King Size Braces (“Those nights were electric! It was just kids having fun, all stage dives, high fives, and the excitement of hanging out on the block outside.”), and happily recounts the tale of catching a classic Canadian punk pairing.

“One of the times BFGs opened for Dayglo Abortions sticks out. Kids went crazy for the Goofs in a way that I hadn’t seen since the ‘80s. I realized that the entire building was full of people participating in a street culture that we all helped create. That was a pretty awesome moment.”

Damian Abraham of award-winning hardcore band Fucked Up also speaks fondly of the punk culture that found a home in the Bop’s rooms. He started going to shows there in the late ‘90s, and thinks of the Bop as “a seminal space.”

“I got to see some amazing shows in the building, like The Swarm’s last show; tonnes of amazing No Warning gigs; the last Our War show, and various incarnations of the Cro-Mags,” Abraham enthuses. “When I was able to finally start playing there, it felt as if Fucked Up had crossed some threshold of legitimacy that my previous bands hadn’t. Also, it is the venue where I saw my future wife Lauren for the first time. ”

Fucked Up played Kathedral and Reverb close to 10 times during the 2000s, including two of their annual Halloween shows, but Abraham’s recollections tend to feature other bands.

“When No Warning opened for Hatebreed there, a bunch of friends they had met on tour from Boston drove up. Up until this point in Toronto, people had been moshing, for the most part, in a very MTV ‘push mosh’ kind of way. When these people from Boston hit the floor and started throwing fists and skanking and getting super low, the Toronto kids took note. From that point on, hard style mashing hit Toronto. [Producer/manager] Greig Nori and Deryck Whibley from Sum 41 were also there, checking out No Warning as a potential new band to manage. They signed them that night I believe.”

There was a heavy crossover of punks and metalheads at the venue.

“My favourite moments at the Bop as a patron were all of Noel’s metal shows,” raves Exall. “Half the time I had no idea who was playing – ‘Some new band from Norway’ – so my housemates and I would end up accidentally seeing Emperor or something.”

Peters did indeed bring in “Norwegian black metal kings Emperor, heading the Kings Of Terror tour.”

It’s one of the shows Peters cites as a highlight in the Bop building. There were many others.

“Bringing Stormtroopers of Death in; they never toured, but did once for Bigger Than The Devil. The bar was almost drunk dry that night,” says the promoter. “Cradle Of Filth made their first-ever Canadian appearance, back when they were still dark and controversial.

“Longstanding relationships I have with some bands were born in the Bop building; Opeth sold out two shows in one month, playing Kathedral first, and then Reverb 21 days later. Last month, they sold out Kool Haus, presented by me. Mastodon played to maybe 20 people their first time through Toronto; Mercyful Fate came through, and then King Diamond the following year. Having Mayhem successfully enter Canada in 2001 for their first-ever Canadian appearance was memorable, as was booking [country act] Corb Lund and the Hurtin’ Albertans only to have maybe 20 people show up. This is only the tip of the iceberg.”

Peters left the Bop behind in March 2003, citing dissatisfaction with in-house sound, Chiaromonte’s raising of rental rates, and having to put out fires (literally).

“It was fun, and it was good to have a home base for four years, but eventually the business of Inertia outgrew what the Big Bop had to offer in terms of quality, capacity and a professional working environment.” (Inertia marks 20 years of presenting aggressive music in Toronto this year.)

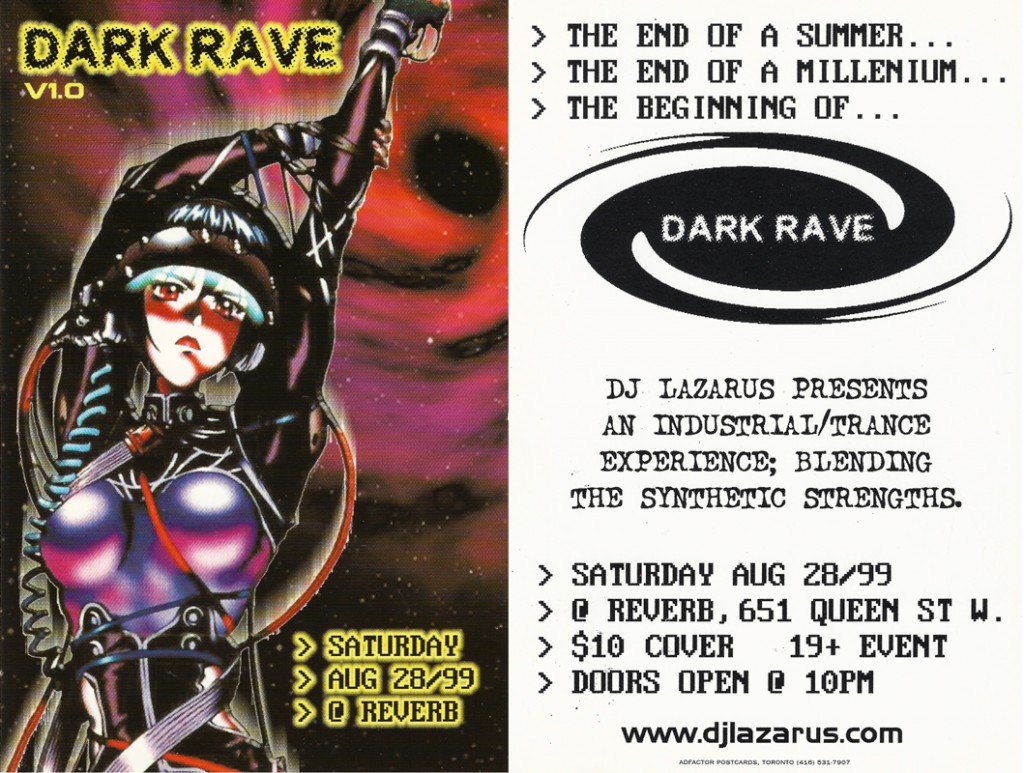

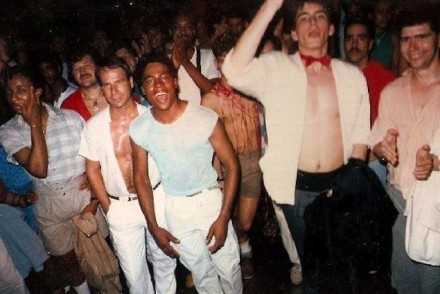

The Bop’s multiple rooms featured far more than rock. The building also became an unlikely home to raves and electronic music. Goodfellaz and Nocturnal Commissions threw a pile of parties there while Shakti Collective presented a number of blacklight trance events. DJs such as Dragnfly, Lady Bass and Unabomber a.k.a. Christian Poulsen (Hugs Not Drugs) were frequently found on flyers listing 651 Queen West as the address. There were the Ipanema raves on long weekends and, of course, there was Darkrave.

Lloyd Warren a.k.a. DJ Lazarus is the driving force behind Darkrave. DJing in Toronto’s alternative clubs since the early ‘90s, Warren began to play at the Bop in 1998, when he moved his popular monthly Fetish Masquerade events over from Club Shanghai (the Subspace fetish parties later took root at the venue too.)

Lazarus launched Darkrave in 1999.

“I wanted to create a rave environment, but with darker edged music,” Warren explains. “Darkrave evolved from featuring mostly industrial to incorporating more psytrance, hardcore/gabber, and dark techno.”

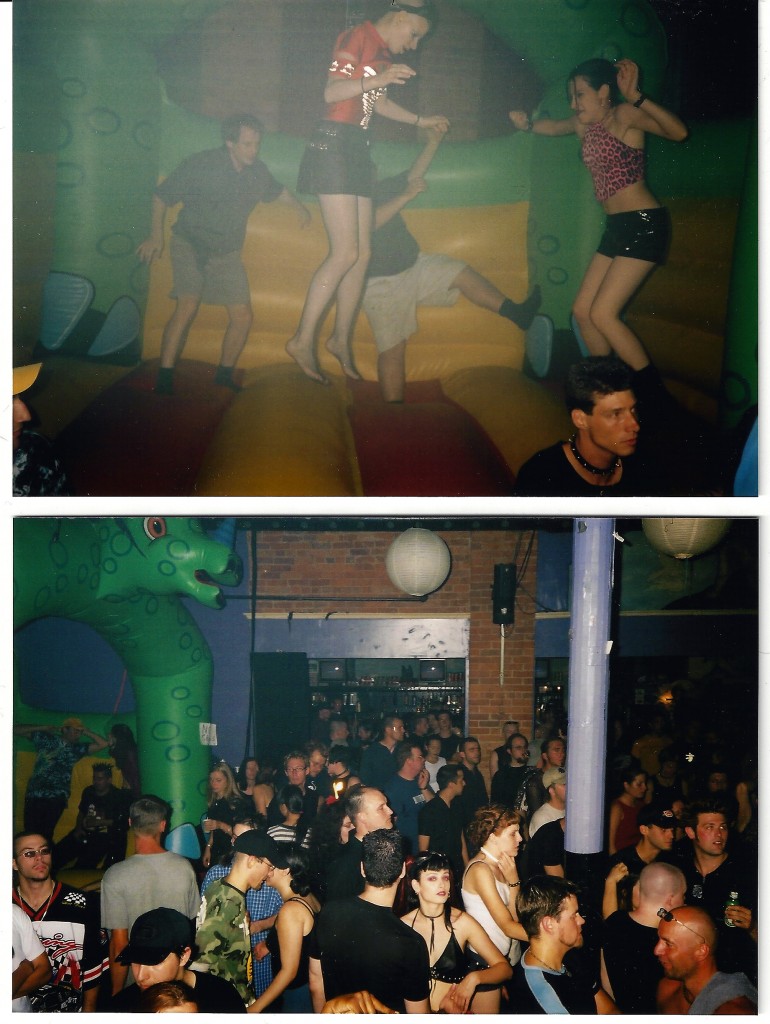

At its height, the monthly party took over the entire Bop complex as it attracted crowds upwards of eight hundred “Goths, ravers, clubbers, normals, and people who just found themselves there.

“The Big Bop was huge and cavernous. It was grungy, a bit run down, and a glorious party space,” Warren describes. “There was always a room or corner to be explored. Multiple staircases led to different rooms, meaning it was easy to get lost. It was dark – eternally night. You never knew what time it was because there were no uncovered windows to let the sunrise in.”

“The Bop was a magical complex,” agrees Greg Gallant who, as DJ Phink, played alongside Lazarus at the Bop for both Darkrave and Fetish Masquerade. “It was multi levels of bouncing, fun times. I remember we got UV reactive bubbles a few times for Darkrave. It was fun watching people catch the bubbles with their faces, and then learn that their face also glowed under black light.”

Darkrave events tended to feature playful props, like UV lighting, cotton candy machines, and bouncy castles. Some parties really stood out.

“The Darkrave with VNV Nation in 2000 was crazy,” says Warren. “I have never seen so many people in the Reverb before. Patrons were literally standing on the wall rails because the floor was so packed. The energy was electrifying.

“One night, an electrical fire started on a hydro pole just outside the Bop. It caused a full blackout inside while hundreds of people were dancing. Instead of everyone leaving, we lit candles and some patrons went on to the stage and started drumming on improvised objects. The dancefloor resumed, and there was a real sense of community.”

Gallant, who had played earlier as Phink at venues including Sanctuary Vampire Sex Bar and Area 51, was also an anchor of the alt-rave community that gravitated to the Bop, as well as to Funhaus, the club Warren operated across the street from 2003 to 2008 (Chiaromontewas a partner). Phink started the Eloko psy-trance series at Funhaus, having already turned heads with parties held at the Bop.

“The first real party I put on at The Big Bop was with my partners in the Deep Sea Fish psytrance collective,” says Gallant. “We brought Infected Mushroom for the B.P. Empire tour, their first time in Toronto. It was a great, sold out event, and they kept the floor bouncing right ‘til 5am.” (A partial list of raves held at the Bop, with flyers, can be found here.)

DJ Lazarus (left) and DJ Phink playing different rooms at a Darkrave. Photo courtesy of Lloyd Warren.

Fact was, you never knew what you’d find in the building from night to night.

“We were mostly known for rock, punk, and metal, but it was common to have metal on one floor, a hip-hop show upstairs, and a singer-songwriter showcase in Joe’s,” reminds core staffer Scoot DeVille. “We were the only venue in the city where you could walk into a punk show on the ground floor, say ‘This band sucks,’ go upstairs and see a touring metal band, again say ‘This band sucks,’ and then go up to the third floor to see Esthero having band practice.

“It was actually really fucked up, but it worked. We had everyone from 14-year-old girls dancing in their bras at a rave at 4:30am, to their moms coming to see the throwback hair metal bands they grew up with.”

Scoot DeVille (centre) with then-Mayor David Miller, and Reverb bartender Helena. Photo courtesy of DeVille.

The club’s lack of curation may have been borne out of necessity, but in the end, it defined The Big Bop.

“Other clubs in the city at the time, and I mean this respectfully, were too well curated to let our type of music or any really outside music happen there,” says Damian Abraham; “But the Bop didn’t give a fuck, and booked in Darkrave, black metal, hip-hop, hardcore, screamo – all the stuff that wasn’t cool enough at the time for some of the other venues in town.

“It was like CBGBs in that way; [CBGBs’ owner] Hilly gets credit for having this amazing ear, but his genius was having an open door booking policy. Television and Ramones were able to play CBGBs when they couldn’t find other places in New York to play. That is the Bop’s gift to Toronto: it wasn’t too caught up in any one thing to prevent the next thing from developing.”

Fucked Up perform “Crusades” at Reverb, 2009. Video posted by PunksAndRockers.com

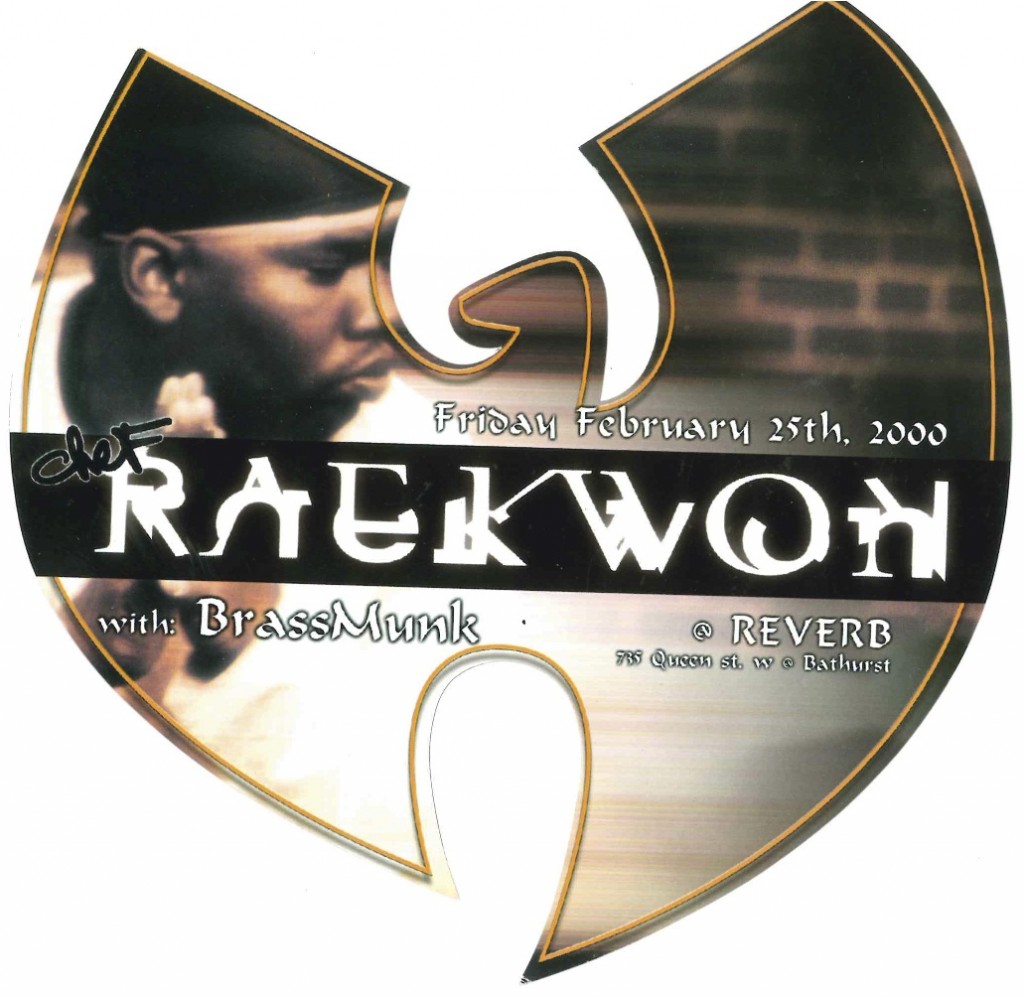

Who else played there: Many who went to Reverb during its early years, myself included, will associate that room with some incredible hip-hop, funk, and soul events. We have promoters Carlos Mondesir of Hot Stepper Productions and Jonathan Ramos of R.E.M.G. to thank for many of them.

Mondesir presented Ninja Tune artists like Amon Tobin, DJ Food, and DJ Vadim, as well as the likes of DJ Cam, Nightmares on Wax, and a very special touring group of turntablists in 1997.

Deep Concentration DJs (L-to-R): Kid-Koala, Jazzbo, Peanut Butter Wolf, Cut Chemist, A-Trak, and Grouch in behind. Photo courtesy of Carlos Mondesir.

“Deep Concentration was a tour for an album by that name featuring Kid Koala, Peanut Butter Wolf, Cut Chemist, A-Trak, and I added Grouch to rep Toronto,” Mondesir describes. “It was probably the best turntablist gig this city has ever seen. A-Trak was added to the bill at the urging of Kid Koala’s manager. We had to make special arrangements with his family for him to come and play. Needless to say, it was nuts.”

Also in ’97, and against many odds, Hot Stepper presented Japanese artists United Future Organization for a sold-out show.

“I did that gig against the advice of my DJs,” recalls Mondesir; “I’d say it confirmed the viability of nu jazz in this city for many. Marilyn Manson also attended, which was really odd.”

On the live soul, jazz and funk tip, Hot Stepper’s signature Bump N’ Hustle series found its footing at Reverb.

“We’ve been doing Bump N’ Hustle so long that many people don’t know that for the first six years or so, it was a full live showcase of emerging soul music artists. Vocalists like Divine Brown, Glenn Lewis and tonnes of others rose through our gigs. Bump N’ Hustle was a massive source of pride in local music ability and community.”

Bump N’ Hustle band, featuring the late David ‘Soulfingaz’ Williams. Photo courtesy of Carlos Mondesir.

Surprisingly, Hot Stepper even did some Garage 416 house events at Reverb, including the presentations of Steve “Silk” Hurley, Joe Claussell, and Pevin Everett with his live band, Seance Divine.

“The Reverb sound was great,” explains Mondesir of presenting Garage 416 events outside of its main home of the time, Roxy Blu.“ Reverb wasn’t aesthetically nice, but turn the lights down, light some candles, roll some cool AV and it’s all good. I used great local AV guys regularly, Projektor and then Mix Motion. That compensated a lot.” (Hot Stepper turns 20 this year, with other mainstay events including Break for Love and their Sunday afternoon summer series at Cube.)

As for Jonathan Ramos, his R.E.M.G. logo was featured on a lot of flyers promoting shows at Reverb.

“Jonathan was instrumental in building a quality hip-hop scene at the Bop,” credits Caldwell. “He opened a lot of doors for Canadian hip-hop artists. [Through his shows] I was fortunate to work with artists such as The Rascalz, Ivana Santilli, k-os, Choclair, Michie Mee, and Classified, plus Jurassic 5, Ursula Rucker, and so many more.”

Ramos, who formed R.E.M.G. in 1993, booked Reverb regularly from 1998 on.

“Their booking policy made it accessible to acts, promoters and genres that didn’t always ‘fit’ at other venues,” writes Ramos.

“At that time, hip-hop wasn’t the omnipresent genre it is today and wasn’t ‘welcome’ in most venues. There was a misconception that these shows came with low bar sales and attracted violence, and as such most venues either didn’t allow the shows or levied prohibitive rental fees.”

Some of the other acts Ramos booked in at the Bop include Dilated Peoples, The Hieroglyphics, The Coup, Spearhead, and The Beat Junkies. There’s one show that still stands out to him.

“Talib Kweli, September 2006. Kweli was at the top of his game, had one of his biggest hits, and was one of the first to put on a young Chicago producer named Kanye West. The energy in the room was palpable. Both Kweli and the fans had an amazing time.” (Ramos remains active as a concert promoter and is now the Director of Live Music for INK Entertainment.)

Talib Kweli live at Reverb in 2006. Video posted by mymanhenri.

Lots of other promoters, performers and DJs took note of the above events and brought in their own. DJs Kola, Serious and Fase produced parties. The Salads hosted their ‘Salad Gold’ series; Shaun Boothe presented The BarberShop Show; and James Bryan performed with loads of different projects, including The Philosopher Kings and Sunshine State. African percussionist Vinx hosted jam sessions that brought out some of this city’s best players and vocalists while local artists Blaxam, Jacksoul, The Pocket Dwellers and Fefe Dobson, among many others, brought the funk and soul.

From Maestro Fresh Wes to Metric or the Misfits, early Death From Above 1979 appearances, and even a Megadeath acoustic show, the possibilities were endless.

“The variety of events that we could be facing from week to week was unbelievable,” summarizes soundman Disman.

“One of the best shows that I remember was Asian Dub Foundation in Reverb, which was packed beyond belief. I was trying to do sound for a show in the Kathedral, with maybe 25 people in attendance, but when the audience upstairs started jumping up and down in time, the ceiling of Kathedral was flexing so much that the bands refused to get on stage. We cancelled the show downstairs, and I went up to join the party.“

Who else worked there: “Soundmen Jake Disman, Aaron Michielsen, ‘Lucy’ David Van Nie, Hiroto Tabata and Brendan Bane were the guys who I depended on the most to ensure the musicians were happy,” credits Caldwell. “They were true professionals who didn’t allow their own personal tastes to dictate their ability to do a great job for artists. Those guys always went above and beyond to make sure the whole night ran smoothly.”

Interviewees repeatedly mention the Bop’s many fine sound techs, with others including the Kathedral’s Mike Unger, and Greg Below, who worked both Kathedral and Reverb before co-founding Distort Entertainment and managing bands including Alexisonfire.

Following Peters and Caldwell as in-house bookers were Rosina Tassone and then Cindy Parreira, who has posted more than 100 live clips from shows at the Bop to her YouTube channel. (Caldwell, who left the Bop in the mid 2000s, went on to work with James Bryan at his UMI Entertainment and continued to book shows. She left Toronto three years ago, returning to Sault Ste. Marie where she now works in animal rescue.)

Clubs of the Bop’s size also rely on a solid bar and security staff, with some of the core members mentioned including Sandy Bergin, Jamie Iker, Karen Neko, Pinky Love, Nina Tereschenko, Andrew Ryan Fox, Sylvana Ched, Steve McLeod, Peter ‘Slim’ Betley, Hubert Wysokinski and Marco Di.

Ken Stone was also a central figure in the Big Bop family.

“Ken was barback in his ‘50s,” shares DeVille. “Sadly, he passed away from lung cancer in 2005. We had a wake for him – Dom actually paid for his cremation – at the Bop. We all went up on the roof, very drunk, and Dom gave us all a handful of Ken’s ashes. We each went to our own little spot on the roof, cried, said a few words, and scattered his ashes. We were truly family; we went through births, deaths, divorces, breakups, addictions, recoveries, everything together.”

Audio engineer Van Nie, who says he mixed 35 to 50 bands a week at the Bop, agrees.

“The Reverb was my second living room; I often spent more time there than at home, as did most of the Bop staff. It was our refuge, our creative outlet. Through the rough times and the happy times, we were one dysfunctional family, raising a new generation of audio engineers, promoters, musicians and bartenders.”

“I used to call the Bop ‘The purple people eater’ because once you came there, you never left,” cracks DeVille, who worked as a busser, occasional bartender, and bouncer.

“If you could work at the Bop, you could handle anything. From drunk minors throwing up on me to holding down a naked man high on PCP screaming about how he was the messiah, I’ve seen it all. Twice. And I wouldn’t change a second of it. That 10 years was the best period of my life, and I miss it every day.” (DeVille now works security at both Sneaky Dee’s and Hard Luck Bar.)

What happened to it: Chiaromonte co- owned the building until 2007, when it was sold to Toronto developer Daniel Rumack.

“I was ready to pack it in,” he admits. “I’d put in so many years, I was drained. During the first years, I even lived at the Bop. I really threw myself into it because I had to.

“By 2007, all of us partners got together and said ‘If somebody comes up with this figure, we’ll sell.’ Somebody did. We had an agreement with him that we would stay on, and if he found someone else, he would give us four months or if I wanted out, I could get out of the lease by giving four months.”

That time came near the end of 2009, when Rumack announced he had a new tenant. This too was timely.

“The last few years were not very well attended, and the building was starting to fall apart,” describes Disman.

The Big Bop went out with a bang on January 30th, 2010. Kathedral featured 20 bands over 12 hours while Nocturnal Commissions and Embedded presented the ‘Good to the Last Bop’ rave on the other floors.

“The last song ever played at the Reverb was by me at the rave,” says Warren a.k.a. DJ Lazarus. “I played VNV Nation’s ‘Perpetual.’ A fitting song for the end of an era.” (Warren currently DJs at Nocturne and Velvet Underground while his roving Darkrave turns 15 this year.)

After the Bop’s close, the southeast corner of Queen and Bathurst underwent a significant transformation. Underneath all that grit and purple paint, 651 Queen West was a beautiful brick heritage building. Following extensive renovations, it opened as CB2’s first Canadian location in January 2012.

Chiaromonte has not yet been inside.

“No, but I’ve heard that you walk in, and see the Big Bop sign,” he comments. “It definitely looks like they did a nice restoration job. And you can’t stop big business.”

Apparently you can’t stop Chiaromonte either. Though he’d planned to retire after selling the Queen West building (“We made good money.”), Chiaromonte opened a new club almost immediately after closing.

“I realized my plans of retirement were bullshit,” he laughs. “Within 24 hours, I found the venue out in the west end that would become Rockpile, and we signed the lease. We grabbed all of the stuff from the Big Bop, brought it to the new location in January of 2010, and opened a couple months later.”

Many familiar faces went with him. Lucy Van Nie coordinated the move, and did the audio and lighting design and install (he went on to work for Guerrilla Remote, and is now works for Westbury and is house tech at The Piston). Jake Disman is house tech of Rockpile West (the short-lived Rockpile East closed in December), and also works as a touring front-of-house tech.

Located at 5555A Dundas West in Etobicoke, Rockpile features tribute bands, indie bands, and even hip-hop shows (Talib Kweli performs there on February 20), with punk and metal at the core. Only this time, all-ages really means all ages.

“You know what’s so cool? Seeing all these old rockers come in with their kids,” says Chiaromonte. “We had the Misfits play both Rockpiles, and it was amazing to see how many of the old punks brought their kids. We were sold out for both shows. And the Misfits loved it.”

Thank you to participants Andrea Caldwell, Carlos Mondesir, Damian Abraham, Dominic Chiaromonte, Ewan Exall, Greg Gallant, Jake Disman, Jonathan Ramos, Lloyd Warren, Lucy Van Nie, Mark Micallef, Noel Peters, Scoot DeVille, Trevor ‘DJ Tex’ Mais and Yvonne Matsell.

7 Comments

A big part of the Bop went completely unmentioned in this article. Craiger with Subspace fetish nights along with many other events and raves he put on with other regular bartenders like Nat and Djs like prospero.

Nostalgia brought me here. What an awesome article about one of my favourite places in the city. Nothing quite like the mosh pits we had in the Reverb… and feeling the floor flexing under the weight of the crowd added to the fun. Can we go back in time, please?

Kingsize was always the best cheers Noel the Barrie boys salute you Mike big al and everybody who created a memorable time

[…] eventually started introducing dance music when I starting dancing at the Boom Boom Room owned by the The Big Bop‘s Ballinger brothers. I hung out with the DJ from the Boom Boom Room […]

I find it funny Rosina gets a footnote as she was responsible for so many shows there.

Ike Turner

U.K. subs

Eric Burden

Vernon Ried

The list goes on

We played there as Zugha over ten times.

She was the heart and soul for years.

Deserves way more then a mention.

Darkrave was always terrific. A great 8 yrs for me. Never really got to thank Lloyd or Greg but you did. I am glad. Thanks.

http://youtu.be/9l5j47RfUHs – link to the moments before I played the last track ever at Holy Joe’s – Born Slippy